Closing the loop: How beneficial ownership information is used and why it matters

This piece introduces Open Ownership’s latest research on beneficial ownership (BO) data use. Aiming to publish our full analysis later this year, here we highlight main findings and new emerging questions. Whilst users can include individuals working in the agency responsible for a BO register, those required to make BO declarations, and those using the information stored in the register, this research focuses on the latter group: the end-users of BO data. The experiences of an increasing number of end-users of BO data – inside and outside government – offer new perspectives from which we can learn from. These experiences help grow the evidence base on the impact of beneficial ownership transparency (BOT) reforms to guide how to implement these reforms effectively. This allows us to close the loop: putting users’ needs at the centre of policy decisions to maximise impact.

This approach has been a core focus of Open Ownership’s work. For example, the Principles for effective implementation focus on maximising the usefulness and usability of BO information. Other organisations have also called for user-centred reforms, but the specific technical and informational needs users may have remains a gap.

Open Ownership’s data use research

Whilst there is still a lot of work to be done with respect to implementation, the growing wave of BOT reforms and the BO information that this has made available to date have allowed researchers and practitioners to start exploring the impact of BOT reforms. At the same time, debates around the accessibility to BO information by various actors have dominated discussions around implementation, with more attention focused on who should have access than what this access should look like. In particular, the 2022 Court of Justice of the European Union (EU) judgement mandated the EU to interrogate which parties need access to what information, in order to achieve which specific goals, and how to balance transparency with privacy rights. Within this context, Open Ownership decided to leverage its global network of end-users to conduct new primary research on the usability and usefulness of BO information.

The research aimed to refine our framework for effective implementation and bring a user perspective to the debates on access by mapping the BO data use landscape. The aim was to develop a conceptual framework for BO data use based on user needs in order to help inform access provisions for BO registers. To date, access to BO registers has largely been organised along the following lines: specific access provisions for certain government users, some for banks and other anti-money laundering (AML)-regulated private sector actors, and, in the case of public registers, other provisions for any other users. This fairly coarse categorisation risks glossing over the specific needs different users may have.

Our initial assumption was that a financial analyst at a financial intelligence unit (FIU) would have more in common with an investigative journalist, in terms of how they need to use the information, than with a fellow government employee using the information as part of a public procurement process. Similarly, the latter would probably have more in common with a business conducting due diligence. An improved access categorisation could factor in different types of use, rather than just the category of actor. This could lead to including FIU analysts and investigative journalists in the same category, with similar access features but different levels of access to sensitive information. Testing this assumption required looking at who current BO data users are, how and as part of which processes they use BO information, what specific requirements they have to use the information in this way, and what their barriers to use are.

To do this, over the course of 2023, Open Ownership’s policy and research team conducted 34 interviews with individuals who used information from BO registers for a variety of purposes. Research participants included users from:

- government bodies, including tax, public procurement, and anti-corruption agencies, and FIUs;

- the third sector, including academics, researchers, civil society organisations, and journalists;

- the private sector, including from the finance and real estate sectors, as well as software, data, and analytics service providers.

The geographical representation of the participants reflects the regional spread in progress and history of BOT implementation. Two thirds were from European countries and one third were from Africa, the Americas, and Asia. The interviews, along with internal documentation of our experiences of and lessons from providing technical assistance, were the basis for our qualitative analysis. This involved developing a conceptual model that looks at data use from an informational perspective and as a multi-stage process, comprising one or more lines of enquiry.

A conceptual framework for beneficial ownership data use

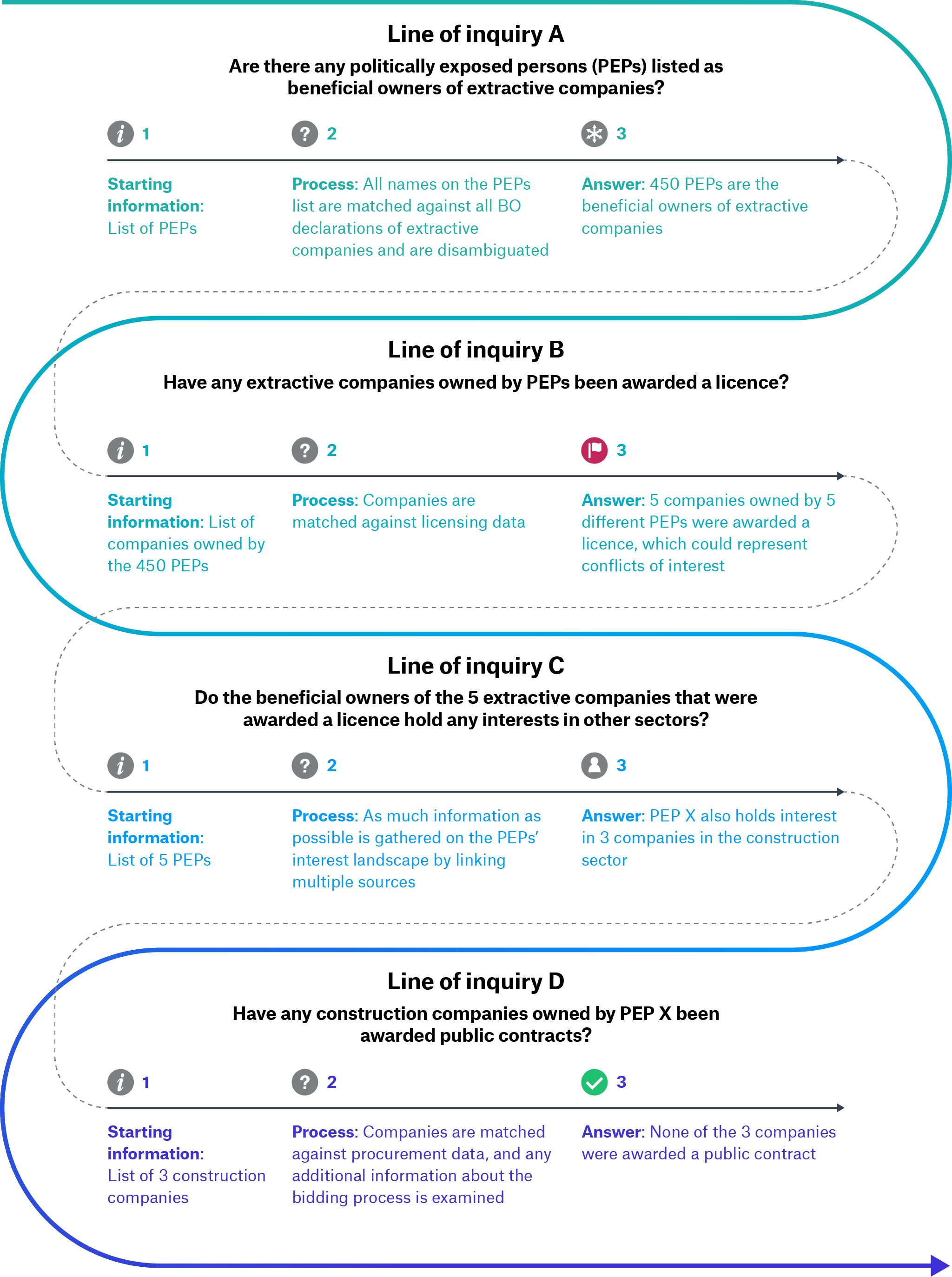

Our new framework looks at BO data use as a multi-stage journey to understand various needs that users have. It takes the question a user seeks to answer as a starting point which leads to a line of inquiry. Data use may comprise multiple lines of inquiry, each seeking to answer different questions, which may involve processing and using BO and other types of information from multiple sources, and generate further lines of inquiry seeking to answer additional questions.

Under each line of inquiry, the nature of the question and its specific characteristics determine specific needs. The framework looks at a variety of elements to understand the fundamentals of data use. For example, it explores:

- whether the nature of the users’ question is qualitative or quantitative;

- the type of information users are starting with, and whether the line of inquiry targets specific individuals or companies;

- the scale and frequency at which users need to process the data;

- the scope of connections that users need to establish across multiple sources of information.

Looking across all these elements, we have reached some initial conclusions that are explained and illustrated using case studies below.

Going beyond professions to better understand data use

We found that specific needs are shaped by the nature of the questions users are seeking to answer, which determines the type of use. However, we also found that the types of questions users are seeking to answer over the course of an inquiry can change, are hard to predict, and are not necessarily unique or specific to a profession, activity, or user profile.

“Sometimes when you are asset tracing, you hear about a person so you go looking for them in the data specifically, whereas other times you may be going through a whole database and look for suspicious things. We use a fishing analogy a lot and talk about pole fishing and trawler fishing.” – Ben Cowdock, Senior Investigation Lead, Transparency International UK

A similar point was mentioned by an interviewee working for a tax agency, who explained that activities in their office could range from auditing specific people suspected of tax evasion, to identifying patterns and indicators of risk. A data use journey may comprise multiple lines of inquiry, with answers to initial questions generating additional, unforeseen questions associated with new sets of needs. This means that many users seek to answer a variety of questions at different points along their journey, leading to different types of use. Users have similar needs across a variety of profiles. This suggests that it may not be practical or useful to develop a typology of data use as a basis for access. Developing a comprehensive view of aggregated user needs and seeking to address them may be more likely to enable effective data use.

Figure 1. Data use journey

This diagram illustrates a data use journey comprising several lines of inquiry. In this fictive example, the user takes steps to answer an initial question (line of inquiry A), which generates additional, unforeseen questions, and lines of inquiry B, C, and D.

The case studies below describe this further. They illustrate how a range of users can pursue different lines of inquiry. These lead to user needs which can cut across different profiles and professions. Analysing the experience of different users helps build a more complete picture of what enables and hinders effective BO data use.

Case studies

Mapping trends and identifying risks

A journalist in Denmark explained how business journalism helps create a transparent and healthy corporate environment and provides valuable information for companies’ and investors’ decisions. “We need to know what’s going on in our country, including knowing who owns what [...],” the journalist said. This involves monitoring, analysing, and seeking to provide an up-to-date and comprehensive picture of the business landscape. BO information is part of this, and the journalists use the company and BO registers daily.

In 2023, Transparency International France and the Anti-Corruption Data Collective combined publicly available BO information in France with information from the real estate register to look into ownership of France’s real estate sector. They exposed that nearly 71% of all corporate-owned French parcels are held by anonymously owned companies. A few years ago, the non-governmental organisation (NGO) Reporters Without Borders and the French academic institution, the Laboratory for Interdisciplinary Evaluation of Public Policies, explored ownership concentration in the French and Spanish media sectors and published a report stating that over half of each sector was controlled by companies from the financial and insurance sectors, whose complex shareholding structures made it hard to identify the beneficial owners. Monitoring and addressing risks linked to ownership concentration is a concern evidently also shared by public authorities. Hence, similar types of analysis have been carried out within government agencies. For example, the Competition and Markets Authority (CMA) of the United Kingdom (UK) used BO data to assess how common ownership affected competition.

In these cases, the lines of inquiries explored by these different profiles of users had a quantitative nature. They were interested in general trends and did not necessarily need to be able to identify specific individuals or companies in the real world for their analysis, for which pseudonymised information may have sufficed. However, when subsequent questions are of a qualitative nature – for example, asking not only “what is the proportion of ownership concentration in the sector”, but also “who are the individuals who most influence and benefit from the sector?” – this requires identifying specific entities and individuals, meaning identifiers and other attributes (e.g. names, dates of birth) become more important. For example, a journalist explored ownership concentration in Armenian media. They looked at Armenian television companies and were interested in identifying specific, powerful individuals with significant influence over the media landscape. Whilst in theory providing pseudonymised data can help enable a range of analyses, these analyses are not always conducted in isolation.

Another common feature in these examples is that they all required processing a large amount of information. This requires certain access provisions, without which processing can be prohibitively resource intensive or otherwise impossible. The CMA could carry out their analysis thanks to publicly available BO data downloadable in bulk format. However, they also needed to match and disambiguate declared beneficial owners (i.e. confirm whether two individuals with the same name refer to the same person or to two different people), using secondary identifying attributes (names, addresses, nationality/ies, month and year of birth) as the UK register does not uniquely identify individuals yet.

Transparency International France also explained the importance of having access to data that can be processed in a useful way. For their research, they had to go through five million individual web pages to connect them to real estate data. This took them several weeks and significant resources. In their publication, the NGO highlighted a major need to support users in carrying out this type of work. They explain that not being able to access data in bulk created “a significant barrier [...] in monitoring the implementation of the beneficial ownership rules”, and that “access to beneficial ownership information in an open data format – or even better, API [application programming interface] access – allows key actors to more effectively use the data”. This suggests that portals which only allow limited flexibility in ways to search and process information are likely to be less impactful than where information is structured and available in bulk.

Qualitative questions and targeted investigations

At times, the same data users sought to answer more qualitative and targeted questions. For example, the Danish business journalist also discussed looking into specific entities and individuals. This could be to write an article to profile a specific company or to carry out an investigation. In one investigation, BO information was used to investigate a case of potential sanctions evasion. Using both the Danish and Czech corporate registers to monitor declared changes in ownership information revealed discrepancies, which raised red flags for further investigation. [1] Similarly, the Armenian journalist went from the initial mapping of the media sector to carrying out more targeted work, focusing on nine television broadcasters. This article discusses potential red flags for specific companies, including the listed beneficial owners of two of the regional broadcasters being a 74-year-old from a small village and a person whose name does not appear in Armenia’s register of voters. It also highlights the case of a company changing its declared owners from being owned by a group belonging to a Russian-born billionaire.

In the initial examples, the Armenian and Danish journalists had more in common with the French researchers or the CMA. However, in these examples, they share similar needs to sanctions compliance officers and FIU analysts. In another interview, a sanctions compliance officer in a bank explained that conducting due diligence on current and prospective clients involves starting with a company name and number, matching it to information in the domestic BO register, exploring links between companies and their beneficial owners, and trying to establish whether any qualitative attributes of the beneficial owners – or information they can connect to them – raises red flags. If any red flags are found, the officer takes additional steps, which usually leads them to consult multiple sources of information across several jurisdictions, including adverse media checks.

A number of user needs are common to the various cases mentioned here. Users are looking at specific individuals and companies, and looking for attributes they have previously defined as constituting risk. The more information is available, the more comprehensive their conclusion. Almost all users highlighted the importance of being able to see historical information and changes over time. Whether it is legal ownership information, BO information from another jurisdiction, lists of sanctioned individuals and entities, or other corporate information, users had to establish links between individuals, corporate vehicles, and assets, and match these across different sources. Many users value ways to visualise connections between individuals, corporate vehicles, and assets to make it easier to understand complex corporate ownership networks.

“If you get a lead, it’s often based on what happened in the past. You often look at who used to own a company. You can look at changes to spot potential red flags. You can’t have the full picture unless you see the history” – Karina Shedrofsky, Head of Research at OCCRP, talking about the importance of recording change over time in BO datasets

Some of these users still required access to the information in bulk because they were not able to search BO registers according to specific criteria or other information they started their journey with. More extensive search functionalities on a BO register and well-designed APIs may therefore help users make targeted queries which would otherwise require bulk access. Such functionalities could mean that the information shared could be limited to what is relevant on a case-by-case basis.

Processing and monitoring data on an ongoing basis

Other users, including civil society organisations from Colombia, Mongolia, and Nigeria, brought together data analysis with journalism and research to support accountability and oversight of the extractive sector. These organisations worked to combine various public data sources and developed analysis tools. For example, the Mongolia Data Club put together data on legal and beneficial ownership, procurement bidding processes and other sources into a digital platform aimed at better understanding the activities and connections of suppliers of state-owned enterprises in the mining sector. Journalists and researchers used their training and tools to explore various questions, for example, to interrogate the fair allocation of coal transportation permits from Mongolia to China. In Nigeria, Directorio Legislativo partnered with BudgIT to build the Joining the Dots platform, which combines BO information, PEPs lists, and mining licensing information to monitor links between politicians and mining licences and automatically raise red flags on a continuous basis.

These users all needed to process a large amount of information, and to establish links and match information from various sources on an ongoing or regular basis, ideally through an API.

These needs cut across different users. Research participants from law enforcement agencies and FIUs value APIs for their ongoing investigative work. For example, an FIU cited their API connections to a range of government information sources as one of the main factors enabling their work. This included the domestic BO register; the Customs, National Identity, Road Safety, Traffic Authority, Immigration, and Tax authority databases; the Central Bank; the Security Exchange Commission; and a number of regulators, including for real estate. UK law enforcement explained how ingesting bulk data from the corporate register into their own database helped to map connections and generate leads.

Linking and matching individuals, corporate vehicles, and assets

In all these examples, using BO information is a step in a longer process that requires multiple sources to draw conclusions. Many user needs stem from attempting to combine BO information with other sources, such as information about real estate, mining permits, PEPs, asset registers, and broader corporate information. The case studies outlined here all illustrate how using BO information is almost synonymous with establishing links between individuals, corporate vehicles, and assets, and matching these across multiple sources of information. This often involves uniquely identifying and disambiguating individuals, corporate vehicles, and assets. The more this can be done by BO registers, the lower the resource burden. For example, because the UK register does not uniquely identify individuals, the CMA first had to match and disambiguate declared beneficial owners using secondary identifying attributes (names, addresses, nationality/ies, month and year of birth) through a resource-intensive process. If the same exercise were to be repeated in Denmark, this would be considerably easier, as identities are verified and individuals are assigned register-specific identifiers.

The way data is processed by many users resembles BO register verification processes, and relies heavily on matching individuals across data sources, as well as comparing similarities and discrepancies between attributes. For example, the compliance officer explained that they had an obligation to verify clients’ identities and carry out checks on entities and individuals who were part of their ownership network, especially if they included foreign entities. This process required matching the individual across information provided by clients and other sources, and comparing the attributes. FIU interviewees also mentioned their API connectivity to multiple domestic databases was critical in order to help match records and spot discrepancies between sources. The accuracy of information therefore plays different roles in different cases. For journalists, public procurement researchers, and law enforcement, discrepancies provide valuable intelligence.

The research also finds that multiple users can form part of a single journey. Data service providers often occupy multiple stages of a journey, spending a lot of time matching individuals, corporate vehicles, and assets across multiple information sources, and identifying connections between them. They fulfil a critical role, often providing services not just for the private sector but also government users, especially with regards to information from various jurisdictions. However, there can be a high cost to entry, especially for some users such as less-resources civil society organisations. Law enforcement officers have repeatedly highlighted the crucial role of civil society actors in meeting their objectives.

”We get many referrals from journalists and civil society organisations. It happens a lot. They are a great source of information. They may uncover offending we were not previously aware of.” – Celestino Calabrese, Deputy Head of Illicit Finance Threat, National Crime Agency of the United Kingdom

Putting users at the centre of beneficial ownership transparency reforms

The insights from the research have implications for the implementation of effective BOT reforms. The research suggests that a large group of users should be able to access the information as structured data and to be able to use this flexibly. It also suggests that implementers should invest in reducing some of the current frictions and resource costs of BO data use (e.g. APIs, ID verification, and assigning unique IDs to individuals).

Some jurisdictions, like the UK, make the information publicly available via a portal, an API, and in bulk, without any restrictions. However, the ways in which information is made available and how flexibly it can be used determine to what degree it infringes on privacy. Therefore, other jurisdictions may be obligated to put in place safeguards (such as legitimate interest access) to make the information available in this way. However, excessive or poorly designed safeguards will also negatively affect the impact of BOT reforms. This raises the question of how best to design safeguards like legitimate interest to enable better and more flexible access to more users and maximise the impact of BO data use.

For example, if access on the basis of legitimate interest is implemented well, and this provides access to high-quality, structured data with a wide range of fields in bulk or via an API, this may lead to more impact than where users are constrained by the use of a public portal with limited search functionality. The EU is pioneering improvements in legitimate interest access through the sixth AML Directive and illustrates the need to foster an ecosystem of different users to complement each other, even in the case of a narrow objective such as AML. Unfortunately the Directive does not require member states to provide bulk or API access.

The research affirmed that many of the aspects covered in the Open Ownership Principles serve to meet the wide range of user needs. In addition, it emphasised the importance of standardising data to maximise usability and impact. Open Ownership’s Beneficial Ownership Data Standard (BODS) provides a concrete solution for governments to move towards collecting, storing, and publishing structured and interoperable data with historical records and visualisation tools. We are also working on advancing the global architecture for interoperable data and enabling effective use of BO information from multiple jurisdictions and its connections to other sources of data. For example, we have started working with partners on the use of identifiers to support the effective connection of BO information with other data sources. Information structured according to BODS can be readily combined with sanctions data, procurement data, legal ownership data, and more to support a range of user needs.

Governments in charge of developing and implementing BO reforms should invest more in user research in their own jurisdiction to test and contextualise these findings. User research should be done on a continuous basis, and increased and sustained engagement between BOT implementers and data users is essential to assess whether policy decisions are effectively supporting the relevant use of BO information. Open Ownership expects to publish a guide on user research in late 2024. Understanding data use also lays the foundation for collecting more robust and empirical evidence on the impact of BOT reforms in the coming years.

BOT advocates have rightfully campaigned for the availability of BO information and access for certain users. This research aims to fill a gap on what that access should look like. As more countries implement BOT and create opportunities to learn from data use, closing the loop means these lessons should continue to inform policy decisions around implementation.

We look forward to publishing further details about user research later this year. If you are currently using BO information in your work and have further lessons to share, or if you are implementing BO reforms and would like to know more about how to better understand user needs, please get in touch with Julie Rialet, Policy and Research Manager at Open Ownership: [email protected].

Footnotes

[1] More can be found about this case in this report by Transparency International.

Related articles and publications

Publication type

Emerging thinking

Blog post

Sections

Research