Striking a balance: Towards a more nuanced conversation about access to beneficial ownership information

The Transparency International and Open Ownership side event on privacy and access at the 2023 OGP Global Summit in Tallinn. (Source: TI US, 5 September 2023).

Since its inception, Open Ownership (OO) has been working on identifying and defining effective beneficial ownership transparency (BOT) reforms and supporting their implementation. Key to this is ensuring that all actors who can use the relevant information to further countries’ policy aims have access to this information when they need it. Simultaneously, governments must strike a balance between the access to this information, and the interference with the right to privacy this causes. This balance is not static, and is evolving and being shaped as contexts and technology change; finding it is not a one-off exercise.

There are no easy right or wrong solutions. The November 2022 judgement of the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU) ruled that indiscriminate public access to beneficial ownership (BO) information for anti-money laundering (AML) purposes within the European Union (EU) was legally invalid. This catalysed discussions at national and international levels, within and between governments, businesses, and civil society. It has highlighted the need to find better, more nuanced solutions to delivering the access that a range of actors need to beneficial ownership data while appropriately protecting other rights.

It is worth exploring this subject by looking at the recent experiences of the EU. Much – but certainly not all – of the initial progress on improving BOT was made in EU member states. Many aspects of that progress have defined emerging good practice and informed the implementation of reforms worldwide. The EU’s landmark data protection legislation, the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), which came into force after the first public BO registers did, has also been a model for data protection legislation worldwide.[1]

While the judgement by the CJEU has no legal implications for countries outside of Europe and certainly does not seem to spell the end for publicly accessible BO registers worldwide – Canada, Nigeria, and South Africa are among others that have actively continued to implement publicly accessible registers since the judgement – many countries in the process of implementing BOT reforms have been following the situation with great interest. Nevertheless, we should be cautious in trying to directly apply lessons from the EU to other places, especially given the context-sensitive nature of the subject.

The EU’s balancing acts (and directives)

The EU’s fourth AML Directive (AMLD4) mandated central BO registers in EU member states. In transposing AMLD4 into national law, member states were required to develop access regimes based on legitimate interest. However, the directive did not prescribe much detail on how to do so and the resulting access regimes were ineffective in practice. Key non-government users who could use the information to help combat money laundering, such as investigative journalists and civil society organisations (CSOs), could either not access the information at all, or could not use the data effectively because of restrictive access procedures. Granted, there are considerable operational challenges to establishing an access regime on the basis of legitimate interest. For example, it is difficult to define the criteria one must meet to be considered a journalist, and for a registrar to design a process to determine whether someone meets these potentially vague criteria. In part because doing so was too challenging,[2] the European Commission required BO information to be made publicly accessible through the fifth AML Directive (AMLD5), rendering these semantic discussions redundant.

While AMLD5 de jure gave rise to public registers, de facto it resulted in highly divergent access regimes, with public access absent in some member states, or limited to residents and nationals. Many countries gave their own, differing interpretations to what constituted a public register, making judgements about which user groups constituted the public, what subset of information they could access, and how and in what form information could be accessed. While public access became a rallying call to allow all actors to leverage the benefits of using BO information in practice, and to provide a practical shorthand to circumvent the complexities of administering an effective legitimate interest regime, it also polarised the discussion into public versus closed.

This seemingly clear goal of establishing a public register undoubtedly encouraged many countries to follow suit, but may have sidelined some of the other options and discussions that could have been on the table. The simplicity of the goal drove significant progress towards greater transparency. However, as more countries made progress with the implementation of their registers, questions such as which user groups should be able to access what information, how and in what form, have arisen and not been answered in a consistent way. In part, as covered later on, this lack of prescriptiveness regarding public registers was a reason for the CJEU to rule that AMLD5 had swung the pendulum too far towards transparency.

The ongoing challenge in the EU and beyond

BOT is a relatively nascent policy area, and has in part grown out of the open government and transparency movement. However, BO information is different from, for example, contracting information because it inherently and necessarily contains personal information, defined by most data protection legislation as information about individual natural persons that allows them to be identified, directly or indirectly. This means that questions around access to BO data require different considerations than access to other types of data. The first registers were legislated for and related privacy impact assessments were carried out before GDPR was adopted, and before widespread evolving technology gave rise to wider public dialogue about the risks (and awareness) of having huge amounts of personal information online.

These risks have changed since then, and so have the values and attitudes regarding privacy and personal data. Simultaneously, the role companies play in our societies and in enabling certain crimes have also changed. COVID-related procurement fraud and corruption, the threat of financial secrecy to democracy itself, and the drive to enforce sanctions on Russian elites following the 2022 invasion of Ukraine, have driven further action towards transparency of company ownership. The premise of companies has always been about affording benefits such as limited liability in exchange for information, such as financial statements and information about directors and shareholders. The liability is instead, to an extent, borne by society at large. For this reason, the South African Constitutional Court ruled that “the establishment of a company as a vehicle for conducting business on the basis of limited liability is not a private matter.”

Many of the specific legal aspects involved in striking the balance between privacy and access to inherently personal data that is BO information have also not yet been tested in the courts. The goal posts are simultaneously shifting and remain only vaguely defined. With this evolution set to continue, balancing privacy with access and transparency is not a one-time judgement call, but an ongoing exercise and practice.

Within this context, Open Ownership has been working to identify emerging good practice on access to data as part of the principles for effective BO disclosure, which aim to ensure reforms lead to useful and usable information. Since 2021, the Principles have posited that public access to BO information is the most effective way to ensure all relevant users have access to such information. They also stressed the need to minimise the interference with the right to privacy through a number of practical measures. These measures include:

- adhering to the data minimisation principle through layered access: that is, making different information available to different users, based on need, and clearly specifying these data fields in law;

- implementing a protection regime: allowing individuals to apply for the removal of their information from a public register where there is a clear safety risk; and

- clearly specifying a broad purpose for BO disclosure in law.

The principles for effective BO disclosure also provide guidance on how information should be made available to ensure it is useful and usable, covering aspects such as searchability, availability of data in bulk and via API, and properly structuring data so that it is interoperable and easily combined with other datasets.

Silver lining to the CJEU decision

While the judgement was broadly seen as a setback to BOT, it included a number of positive points. First and foremost, a follow-up statement to the judgement confirmed that a broad range of actors outside of government – including “press and civil society organisations that are connected with the prevention and combating of money laundering and terrorist financing”, and anyone likely to enter into transactions with a company – do have a legitimate interest in accessing the information. This directly rebuts the argument previously used by many privacy advocates that combating money laundering is within the purview of the state alone.

Additionally, the judgement and the preceding opinion of the Advocate General (AG) confirmed that many BO registers were already on the right track of mitigating interference with the right to privacy, for example by implementing protection regimes. One of the issues was that their implementation was neither required by the directive, nor the conditions for individuals to qualify for protection sufficiently defined. While AMLD5 stated that “Member States may [emphasis added] provide for an exemption from such access to all or part of the information on the beneficial ownership on a case-by-case basis,” the AG’s opinion states that “Member States are not only entitled to provide for exemptions from access by the general public [...] but are obliged [emphasis added] to provide for and to grant such exemptions where [...] that access would expose the beneficial owner to a disproportionate risk of interference with his or her fundamental rights.” Additionally, layered access and clearly specifying what information should be made available in each layer can help make interference with privacy rights caused by the access to BO information more proportional. One key problem raised is that the Commission did not limit which fields should be made available, with the opinion stating that additional information beyond what was specified “does not appear to be necessary for the purposes of identifying beneficial owners either.”

Findings of Open Ownership’s legal research

Following the judgement, OO commissioned legal research into privacy and access to BO information in central registers established by governments. Between March and June 2023, OO’s policy and research team collaborated with Massimiliano Carpino, an experienced lawyer and Adjunct Professor of Data Protection Law and Corporate Governance at the Catholic University of Milan, with expertise spanning both anti-money laundering and data protection law across the EU. The research aimed to answer:

What are the main policy, legislative and technical design considerations that affect proportionality and necessity with respect to the publication of personal information to achieve certain policy aims, applicable to beneficial ownership transparency?

The research looked into the core issues highlighted by the judgement. While the research is heavily informed by EU law and case law, it also aimed to extrapolate lessons that could inform thinking beyond the EU.

The research started from a few premises which are helpful to keep in mind.

- First, beneficial owners, by definition, are natural persons, so BO information inherently constitutes personal data under many data protection laws. This information is therefore governed by data protection legislation.

- Privacy as a legally-protected human right is practically universal, and data protection is increasingly following suit, both in the EU and beyond.[3]

- Therefore, even where BO information is publicly accessible, and irrespective of its data licence, it must still be processed in line with relevant data protection legislation, which places limits on how it can be used.

- Any access to this personal data constitutes processing, and therefore a limitation of the full enjoyment of these rights. Beneficial owners, just like any other natural persons, have the rights to privacy and data protection.

- Nevertheless, these are not absolute rights. This means they can be limited in certain circumstances. For example, if it’s in the general interest to do so or when it is in conflict with other rights.

- A law that enables access to and processing of this information should therefore be necessary to achieving its specified purpose, and this should be proportional to the interference with the rights it causes.

The research highlighted how the extent of the interference with the rights to privacy and data protection depends on how access to the personal data is provided. Conceptually, most legal frameworks allow countries to require companies to disclose personal information about their beneficial owners, and for that information to be accessed and processed for a range of purposes by a range of actors to benefit the public interest. These include a member of the public exercising oversight and accountability over a legal entity which has conferred the benefits of limited liability on individuals.

However, the legal research highlighted two key issues with respect to how the balance is struck between granting access and protecting privacy. The first issue is that providing indiscriminate public access to beneficial ownership information makes it impossible to oversee and ensure that the information is actually being used for the designated purposes (in the case of the EU, for purposes of fighting financial crime), and to monitor and guard against the potential consequences of misuse. This misuse could include combining the information with other datasets to facilitate illicit activities. It is important to bear in mind that an individual's privacy and data protection rights could be violated even without them experiencing any evident harm.[4]

The interference with the right to privacy that arises from indiscriminate access to BO data exists irrespective of the purpose of accessing the data. So even if a jurisdiction is making information available to improve public procurement – rather than just for AML purposes – achieving this goal by enabling indiscriminate public access still creates this potential risk of use of data for other purposes.

A second issue is that a key cause of privacy interference includes the opportunity for data to be misused, particularly by actors in national contexts without robust data protection laws regulating and limiting how personal data is processed within those jurisdictions. Commonly, under data protection legislation, you become a data controller when you access the data. From that moment onwards, how you can process the data and for what purpose is limited by law, and how you use the data becomes your responsibility. So at least in law, you can be held accountable for the use of that data. When the information is accessed by individuals in jurisdictions without similar data protection controls, this accountability is absent.

Potential ways forward

The research and the thinking of OO and its partners has provided a foundation for identifying ways forward. The findings are cause for some optimism about public access to BO registers, but suggest stricter measures should be put in place to mitigate privacy interference in contexts with a lower threshold for privacy protection. All the things that make information easier to use also make it easier to abuse. Combining indiscriminate public access with maximum data auditability may create disproportional and unnecessary privacy risks. Mitigation measures can include things like requiring registration of the person who is accessing the data, maintaining some form of access logs – recording whether someone accesses the information, when, or even what – and placing restrictions on auditability, such as only being able to search by company name, rather than a person’s name. Another measure can be requiring certain data users to prove their legitimate interest. This could justify users being able to access more information than what has been typically made publicly available to date. We need to consider which specific conditions and characteristics of access are appropriate for different actors and use-cases, that can exist concurrently in a system. It could therefore not be a question of public versus closed, or public versus legitimate interest, but access for government, those with a legitimate interest and the public.

All the things that make information easier to use also make it easier to abuse.

In general, governments should begin by assessing their legal obligations under national instruments, for example, constitutions or data protection legislation, and international instruments, such as human rights treaties or conventions. For instance, the Canadian province Ontario’s definition of personal information limits it to “information that identifies an individual acting in a personal capacity. [...] As a general rule, information about an individual in a business, professional or official capacity is not considered personal information.” This differs greatly from the definition in the EU’s GDPR.

Governments should look at the policy objectives they want to achieve, and take stock of all potential data users that can use the information. They should evaluate how they can ensure that these actors have access to the specific information they need and, to the extent possible, maximise privacy protection without compromising on data usability. This will require making judgements about different data users, their specific purposes, and privacy. As part of general good policy-making and governance, governments should conduct impact assessments before the reforms, and evaluate this afterwards.

For all user groups, we should develop a clear understanding of the specific data they need for their specific purpose, and clearly specify this. Each user group should have access to this data, and not to any additional information unnecessary for the use-case (the minimisation principle in data protection). This also means that if a journalist needs a bulk dataset in order to analyse it to find high risk patterns or suspicious corporate structures, then this is the minimum data to which they need access.

Developing this understanding will require a lot more work on the different use-cases of BO information, and may require us to think more about how information is being used and not just by who. There is risk here of stratifying access to the nth degree, which would undoubtedly undermine the overarching aim of facilitating effective access, and the ability of countries to practically implement these access regimes. Data user mapping research, which OO has started carrying out with data users from governments, businesses and civil society actors, should inform which layers should exist. How many, and which layers, may also vary according to the practicalities of implementation in different country contexts. To date, many BO registers have had one or two layers, and in some cases three – a full set of data available to law enforcement and competent authorities, and a subset of data fields made publicly available. Financial institutions in some cases have had dedicated access, and in some cases access along with the general public. This approach potentially falls short of providing the most effective and balanced access for all user groups, as this may not cater to specific user needs. Additional layers of access may give specific non-governmental users such as journalists and civil society organisations access to more information than they currently have access to, with appropriate safeguards, and which they need to achieve their aims.

Next, governments implementing BO registers should invest in tools or methods of ensuring that information is used for the purposes specified in their policies and legal frameworks, and some means of ensuring accountability. Licences specifying what users may legally do with the data may offer solutions in providing some minimum conditions of use, and a basis for legal recourse in the case of abuse. Other methods may involve some form of being able to audit who has accessed what and when, in specific cases. This does necessarily need to be applied to those that have demonstrated a legitimate interest, and under no circumstances should companies or their beneficial owners ever be informed of who has accessed their information, given the obvious security concerns that arise from this. There are important questions around how this would work in countries where the key driver of BOT has been to allow citizens to exercise accountability over their government, and in particular in contexts where trust in government is limited, and civic space under pressure. Placing the decision with governments on who is allowed access would severely undermine this, and capturing information about the users of BO data could present very real risks, and must be considered carefully. The steps governments take should be reasonable and not excessive.

For any of this to work, ensuring data quality becomes even more important. Not only is data quality a requirement under international AML standards and critical from the perspective of data usability, it is also a key data protection element. Data quality will become significantly more important for any system that shows more limited information.

Responsible implementation

Responsible implementation does not mean abandoning public access. It does mean that countries should carefully evaluate and come to judgements about users of BO information, use-cases (purpose) and access, and take reasonable steps to ensure data is being used for the intended purposes, while having avenues for detecting and holding to account those who do not.

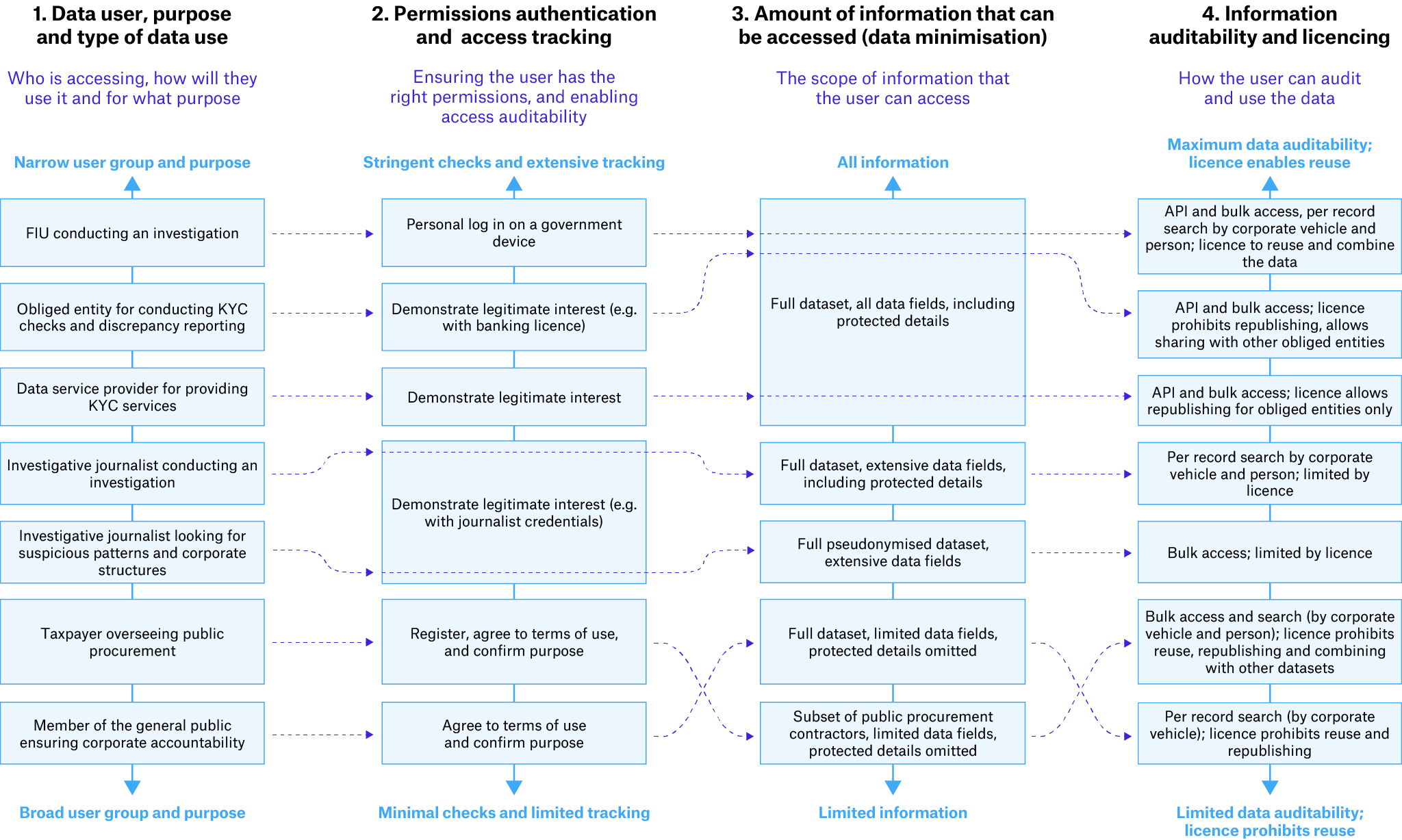

Figure 1. A hypothetical example of a layered access regime in a context with a lower threshold for privacy protection, combining public access with access based on legitimate interest

A graphical representation of different accesses that could exist alongside each other in a single access regime. Access is not about public or closed, but rather about making decisions about: (1) different data users, their purpose and type of data use; (2) how to authenticate their permission and create accountability for their use of data by potentially logging some information about their access; (3) the amount of information that can be accessed; and (4) how the user can audit and use that information.

Although this may sound somewhat arduous, countries that already provide public access to large amounts of data are doing this. The UK, for example, has made judgements about what information to make available to government users, and what information – and how – to the public, and is implementing a protection regime for those most at risk. In its privacy impact assessment, the UK mitigates the risk of identity theft by opting to redact the day of the date of birth on the public register. The UK regime complies with its data protection legislation by requiring the agency (Companies House) to make information public by law.

On the other hand, Companies House does provide indiscriminate public access to the information in bulk and via an API, and “imposes no rules or requirements on how the information on the public register is used.” Legal scholars have raised their eyebrows at this approach, and question its legal validity. The UK government states, however, that through its expanded protection regime it is meeting its obligations to the European Convention on Human Rights. The UK expanding its protection regime means it also acknowledges that the context has changed, and is at least trying to meet its responsibilities in responding to this. However, only the European Court of Human Rights can provide the final word on this.

Grounding solutions in practical realities

In the context of fast-evolving technologies and proliferation and availability of personal data from multiple sources, the combination of indiscriminate public access with maximum data auditability may create new risks that are disproportionate and unnecessary to achieve the stated objective. The balance between the right to privacy and the risks to this right related to the ease of access warrants a closer inspection. Implementing governments should consider what aspects of access can be changed to better safeguard rights, without overly sacrificing the usefulness and usability of the information. Shifting the discussion to how we can find that balance, rather than debating public versus closed, may be a productive way forward. There is a significant amount of work to be done to ensure that solutions are grounded in the practical realities of implementation and data use. There is an urgent demand for this from countries that are currently implementing reforms, including many with which OO is directly working.

OO aims to respond to this demand in a practical, pragmatic way. Partner organisations like Transparency International, alongside whom OO recently presented some of these thoughts in the margins of the 2023 OGP Global Summit, are taking a long-term view on the debate, reminding us that concepts such as privacy and legitimate interest have not been clearly or internationally defined, and that these norms shift. For example, should information about a person acting in a business be considered personal information, which is not the case in Ontario? To what extent can the establishment of a company operating in the public sphere even be considered a private matter? There is a need for a broader dialogue between governments and citizens about all these issues, beyond just consultations, as well as practical solutions to enable effective implementation.

Closing thoughts

Previous experiences with legitimate interest may not inspire a huge amount of confidence. The EU is once again having discussions around whether a former businessman who spends a lot of time digging things up about a local utilities company, and publishes articles and podcasts on the subject, can be considered a journalist. Designing access provisions that can be implemented across multiple countries that deal with these questions in a somewhat standardised way is challenging. However, AMLD5 meant that member states were never forced to make legitimate interest work, and there may be some solutions in new technologies that have emerged since then.

In the meantime, the EU Parliament has put forward some unexpectedly ambitious proposals around legitimate interest, although it remains to be seen if these proposals will survive the trilogue. These include a long list of parties that have legitimate interest by default, only requiring users to renew access credentials every two years, access granted in a single member state granting access in all member states, and requests for access by legitimate interest holders needing to be responded to within a set maximum time after which access is automatically granted. There have also been a few promising developments in other countries. For example, journalists in Luxembourg can access the register with a digital token issued by the press association, relieving the registrar of determining who is a journalist. In Denmark, there are proposals for combining identification with a declaration of faith of legitimate interest, with continuous random checks. This combines government trust in citizens with the government taking reasonable steps to be able to audit access.

BOT reforms are grounded in the social contract between governments and citizens, perhaps especially in contexts where trust in government is limited, or civic space is under pressure. The reforms are premised on the assumption that governments have the right intentions, and will not use the information to further restrict civic space. The risk of governments misusing BO data is perhaps a more immediate concern in contexts where civic space is already restricted than any potential risks to users that may arise from taking steps to monitor data use. Emerging evidence from academic research that OO is funding suggests that BO reforms are more effectively implemented in contexts with high levels of corruption but also with high levels of democratic participation.

Effective implementation of legitimate interest in the EU (as sketched out by Transparency International) may partially undermine one of the key arguments for public access, especially if this facilitates specific users combining information from multiple countries. Conversely, a repeat of the AMLD4 legitimate interest experience will bolster calls for public access. An effective access regime including legitimate interest may also help broaden access to information to parties outside of governments in countries where public access was never going to happen. As an organisation with a legitimate interest, OO potentially stands to gain more and better access to BO information from EU member states than under AMLD5. Responsible implementation of public access in other jurisdictions may help safeguard this access in the face of potential future legal challenges in those countries. Perhaps there would still be a modicum of public access in the EU if the Commission had been more prescriptive in their safeguards.

Although it would have been the easy solution, it was becoming clear that the world was not going to unite behind the principle of indiscriminate public access to BO information – despite a number of countries proceeding to implement this. Arguably one of the biggest barriers to achieving Open Ownership’s mission – to see a world where beneficial ownership data is available and well-used by actors across diverse sectors and societies to improve accountability – has not been a lack of adoption of public access. Rather, it has been the lack of adoption of any type of standard around access at all that has been a key obstacle to widespread data use. The EU will be a testing ground that may see an ambitious directive that is practically, effectively and creatively transposed by EU member states. This experience, along with other countries responsibly implementing public access and the evidence that emerges, could feed into a global conversation which may inform international standards. Hopefully a more nuanced conversation about access will give rise to a policy standard around access that more countries can unite behind.

As Open Ownership is developing its thinking on this subject, we are keen to hear from others in our network. If you would like to share your thoughts, please email [email protected].

End notes

[1] For example, in Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Japan, Kenya, Mauritius, South Africa, Republic of Korea, and Turkey.

[2] In response to being asked whether the Commission had “considered proposing a uniform definition of ‘legitimate interest’, in order to offset the risk that the obligation for any person or organisation to demonstrate such an interest, as initially provided for by [AMLD4], might lead to excessive limitations on access to information on beneficial ownership, owing to differences in the definition of ‘legitimate interest’ in the Member States”, the Commission responded that it “observed that the criterion of ‘legitimate interest’ was a concept which did not lend itself easily to a legal definition and that, while it had considered the possibility of proposing a uniform definition of that criterion, it had ultimately decided not to do so on the ground that the criterion, even if defined, remained difficult to apply and that its application could give rise to arbitrary decisions.” This was not considered a sufficient reason to provide indiscriminate public access by the CJEU.

[3] Data protection is connected to the right to privacy, but is not exclusively a subset of this right. There are gaps in the global protection of data protection as a human right (e.g. the United States). A number of international legal instruments – including the EU Charter of Fundamental Rights and the Council of Europe’s Convention 108 – as well as many countries – for example, many of those that have ratified the American Convention of Human Rights – explicitly articulate data protection as a unique right. For more information see Taylor, Mistale. 2023. Transatlantic Jurisdictional Conflicts in Data Protection Law. Cambridge University Press.

[4] See, for example: Marko Milanovic, ‘Human Rights Treaties and Foreign Surveillance: Privacy in the Digital Age’ (2015) 56(1) Harvard International Law Journal 81, 134 citing Huvig v France App no 11105/84 (ECtHR, 24 April 1990) para 35.

Related articles and publications

Publication type

Emerging thinking

Blog post

Sections

Implementation,

Research

Open Ownership Principles

Central register,

Access