Beneficial ownership data in procurement

Overview

Procurement is the purchase of goods, work, or services. As part of minimum reassurances during a purchase, most customers want to know who they are buying from. This is true when businesses purchase goods, work, or services (procurement), as well as when governments do so (public procurement). Twelve percent of global GDP was spent on public procurement in 2018, [1] with lower income countries tending to spend more proportionally, [2] amounting to USD13 trillion per year. [3] In order to know who governments are really doing business with, it is essential to know who directly and immediately owns a company (legal ownership), as well as who is the beneficial owner ultimately benefiting from and exercising control over a company.

Knowing a company’s beneficial owner can help reveal a legal entity’s true ownership structure. Many governments have committed to beneficial ownership transparency (BOT) – that is, the collection of companies’ beneficial ownership (BO) data by governments in a register and subsequent publication for public oversight – as part of anti-money laundering and combatting the financing of terrorism (AML/CTF) policies. Beyond this, beneficial ownership data is valuable in helping to manage operational, financial, and reputational risks by revealing who really owns and controls companies. There is a growing recognition of government-run, central, and open registers as a primary source of this data. [4]

Whilst managing risk by using different kinds of ownership information in public procurement is not new, governments’ using data collected and published as part of BOT remains relatively unexplored. [5] A growing number of countries, including Bangladesh, Colombia, Egypt and Moldova, have started implementing BOT solely for public procurement purposes. [6]

Typically, governments have procurement policies that aim to prevent corruption and fraud as well as foster fair, equitable competition and transparency to deliver value-for-money services for taxpayers. Governments have more recently begun seeking additional policy aims through public procurement (for instance, to ensure gender equality and social inclusion (GESI), or to foster innovation).

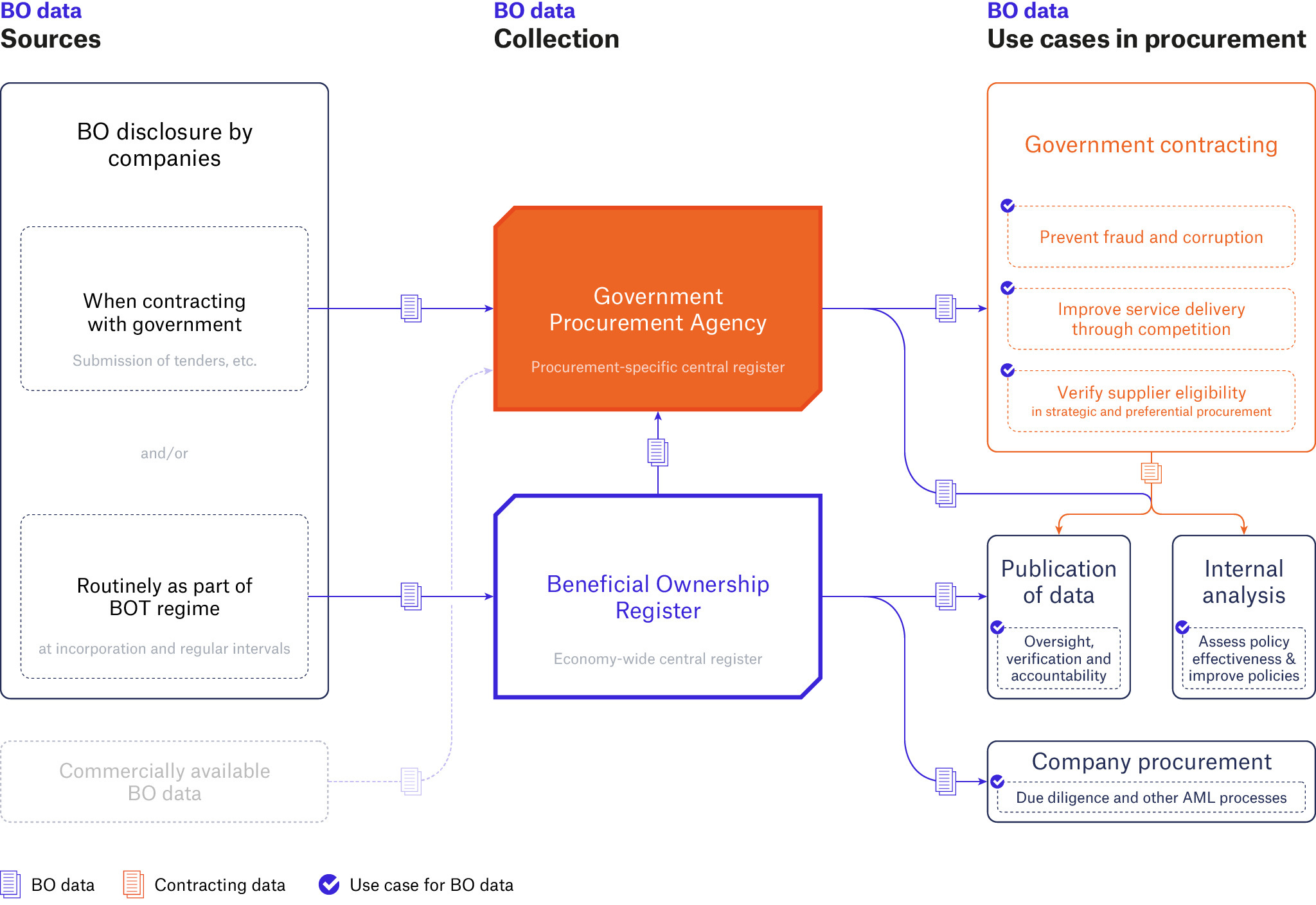

This policy briefing outlines the following ways BO data improves public procurement processes and objectives:

- Prevent fraud and corruption by helping detect potential signs of bid-rigging and conflicts of interest;

- Improve service delivery through competition by managing risk to expand and diversify the supplier base;

- Verify supplier eligibility in strategic and preferential procurement where this is based on ownership;

- Oversight, verification and accountability by civil society and the public through the publication of data;

- Assess policy effectiveness and improve policies by analysing BO data together with other datasets such as open contracting and spend data;

- Improve procurement indirectly on a systemic level by improving the business environment, allowing companies to use BO data to manage and reduce risk in their own due diligence and other AML processes.

For implementers, the briefing outlines a number of decisions to be made about when, where, and how to collect data, and how best to verify it, all of which will affect if and how governments can use BO data in procurement. Most of the case studies focus on national level public procurement and can be applied to local government procurement, where due diligence is typically lower.

Currently, not many governments appear to be using BO data in procurement. Where governments have implemented BOT, this data is not being used systematically in procurement processes. Doing so would be a relatively basic step that could deliver tangible benefits. For jurisdictions that have yet to commit or implement BOT the examples and research in this briefing provide a useful basis to improve procurement.

Figure 1. How beneficial ownership information improves procurement

Governments can collect BO information in central registers as part of procurement-related interactions with companies or for all companies in an economy (page 17). Economywide registers are a useful reference dataset for procurement agencies and are a source of potentially higher quality data (page 18). Commercially available BO data is also a potential data source, although issues with coverage have been raised. They cannot guarantee the coverage that government-run registers can (page 18).

BO data has a number of use cases directly in procurement processes (page 9). Data from public economy-wide registers also have indirect benefits for procurement systems as companies can use this data to manage and reduce risk in their own due diligence processes (page 16). Combining BO and contracting data allows for policy analysis so assess the effectiveness of procurement policies and to inform future policies (page 18). Publishing data allows for public oversight and accountability, and verification. It allows civil society to better understand and analyse government spending, and deters potential wrongdoing (page 19).

Source: Adapted from mySociety and SpendNetwork

Footnotes

[1] Erica Bosio and Simeon Djankov, “How large is public procurement?”, World Bank Blogs, 5 February 2020, https://blogs.worldbank.org/developmenttalk/how-large-public-procurement.

[2] Simeon Djankov, Federica Saliola, and Asif Islam, “Is public procurement a rich country’s policy?”, World Bank Blogs, 1 December 2016, https://blogs.worldbank.org/governance/public-procurement-rich-country-s-policy.

[3] “How governments spend: Opening up the value of global public procurement”, Open Contracting Partnership (OCP), 2020, https://www.open-contracting.org/what-is-open-contracting/global-procurement-spend/.

[4] “Global Anti-money Laundering Survey Results 2017”, Dow Jones and SWIFT, 2017, 25, https://fraudfighting.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/ RC_AML-Survey2017_v5.pdf.

[5] “2016 Procurement Framework: Mandatory Direct Payment & Beneficial Ownership”, World Bank, April 2018, https://nl4worldbank.files.wordpress.com/2018/05/direct-payment-and-beneficial-ownership-outreach-programapril-2018.pdf.

[6] “WP1502: Beneficial ownership transparency and open contracting and public procurement (comments from Anti-Corruption Summit)”, Wilton Park, 2016, https://www.wiltonpark.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/WP1502-Comments-on-beneficial-ownership-transparency-and-open-contractingand-public-procurement-at-Anti-Corruption-Summit.pdf; “IMF COVID-19 Anti-Corruption Tracker”, Transparency International, 20 September 2020, https://www.transparency.org/en/imf-tracker.