Beneficial Ownership Transparency: A Guide for Parliaments

Legislating Beneficial Ownership Transparency

The National Assembly of Armenia. Source: Ruslan Harutyunov on Shutterstock

Due to the differences in legal systems and contexts, there is no single best way to legislate for BOT. [1] The approach should be informed by many factors, such as the legal and regulatory context, including the jurisdiction’s legal system, form of government, institutional capacity and, more importantly, the policy objectives of the reforms. While the specific drafting, codification and implementation processes might vary according to each country’s specific context, the core components of a robust legislative framework discussed below apply in all cases.

Legislating for BOT can be achieved through a single piece of legislation, through an omnibus bill, or by amending one or several existing pieces of legislation, each with specific advantages and disadvantages. Central to the success of any legislative approach is clarity over objectives and consistency in how these are achieved. As mentioned, governments tend to implement more effective reforms where genuine domestic policy objectives are pursued.

An additional consideration is also on where to place provisions in legislation – in primary or secondary legislation. [2] It is typically more time-consuming and laborious to amend primary legislation than secondary legislation. Primary legislation may also require a higher level of technical knowledge among lawmakers. Alternatively, placing certain details in secondary legislation can enable an iterative approach, provided there is a sufficient level of technical and legal knowledge in the executive to produce delegated legislation. For example, the U.K. passed its initial legislation in 2015, expanded its scope to include an additional corporate vehicle type in 2017, and passed additional legislation in 2022 and 2023. The 2023 amendment gave the U.K. BO registrar, Companies House, powers to “check, remove or decline information submitted to, or already on, the Company Register,” among other things, such as regulations on crypto-assets. The 2023 amendment was welcomed by many, including the director of the U.K. Serious Fraud Office and Transparency International UK. The 2023 amendment also raises the cost of business incorporation. The fees will fund Companies House to enforce these new measures.

Zambia passed initial legislation in the Companies Act of 2017, published secondary legislation in 2019, and subsequently amended the Companies Act in 2020 to update its definition of a beneficial owner and define key terms used in the definition.

A checklist of the components of effective BOT legislation, with relevant country examples, includes:

- Clear objective(s) for implementing BOT reform (Kenya, United Kingdom)

- A unified definition of BOT across all relevant legislation (South Africa)

- Setting out clear reporting obligations (by who, to whom, how, when, and what) (Denmark)

- Establishing the register and delegating powers to the registrars (Argentina)

- Verifying accuracy of information (Philippines, Slovakia)

- Mechanisms for accessing information (Armenia)

- Penalties for noncompliance (Seychelles)

Legislatures also need to consider the legislative landscape as a whole, identifying whether any other existing legal provision must be streamlined with regard to beneficial ownership, such as those concerning tax and fiscal issues, procurement transparency, political finance, AML, privacy, and banking licensing and supervision. If needed, these existing policies should be updated. In all cases, globally accepted best practices on legislative drafting and regulatory policy should be applied with continuous public consultations to understand the impact of and update policies.

The Argentine National Congress. Source: Anibal Trejo on Shutterstock

Setting Out Clear Objectives

The objective of a law is its backbone. Anchoring policy objectives broadly in the public interest, as opposed to narrowly in anti-money laundering, is particularly important concerning broader access and transparency. Parliaments must scrutinize the legislation’s objective and then ensure its provisions are consistent with its policy objectives and that these provisions are necessary and appropriate to achieving those objectives. This may include reviewing policy documents – including white papers, impact assessments, and consultations – or mandating periodic effectiveness reviews by oversight institutions (such as the Government Accountability Office in the U.S.) to assist efforts to improve the BOT legislation. Consultations with experts, civil society, the private sector and other stakeholders can assist parliaments with this process and enable legislatures to define the policy goals for BOT reforms.

"Parliaments must scrutinize the legislation's objective and then ensure its provisions are consistent with its policy objectives and that these provisions are necessary and appropriate to achieving those objectives."

Defining Beneficial Ownership of Different Corporate Vehicles

Parliaments need to clarify and define foundational concepts and ensure there is a unified definition in primary legislation, with additional legislation referring to this definition, specifying what the definition means when applied to different corporate vehicles, such as companies or legal arrangements. This unified definition will ensure coherence across legislation and enable verification mechanisms like discrepancy reporting to function effectively. In its definition of ownership, legislation should, at a minimum, contain the following components:

Definition

- Specify that a beneficial owner must be a natural person who ultimately owns, controls or derives significant benefit from a corporate vehicle. “Ultimately” means that the individual can hold beneficial ownership both directly and indirectly.

- Specify a non-exhaustive list of criteria that constitute beneficial ownership, including a broad catch all clause.

- For legal entities, set thresholds (e.g., 5–15 percent) for beneficial ownership criteria based on common forms of ownership and control (e.g., share ownership and voting rights), considering a risk-based approach for specific sectors, industries or individuals based on policy objectives.

- Consider explicit prohibitions, such as for agents, custodians, intermediaries and nominees, from qualifying as beneficial owners.

- Consider explicitly clarifying that joint action by two or more individuals meets the criteria, considering each as a beneficial owner with combined ownership and control, and when joint action is assumed.

Coverage of Different Corporate Vehicles

- Define in further detail what beneficial ownership means when applied to different legal entities and legal arrangements in respective legislation, covering all corporate vehicles with or without distinct legal personalities.

- Define and justify any exemptions from full declaration requirements in secondary legislation, subject to ongoing reassessment against policy aims. This can include, for example, where corporate vehicles are already disclosing sufficient information through a different mechanism, and this information is readily available. Make the basis for exemptions clear and public, and mandate declarations for exempt corporate vehicles, providing the basis for their exemption and sufficient information to access relevant information.

Setting Out Reporting Obligations

To be effective, relevant pieces of legislation must clearly set out who has to report, which is typically the company itself. According to the FATF, companies must maintain and hold up-to-date information about their beneficial owners. Legislation may give companies powers to help obtain this information from individuals that they know to be or have reason to believe are beneficial owners by sending notices or stopping certain rights, like dividend payouts.

Legislation must clearly specify the events that trigger reporting to ensure information is up to date, for instance:

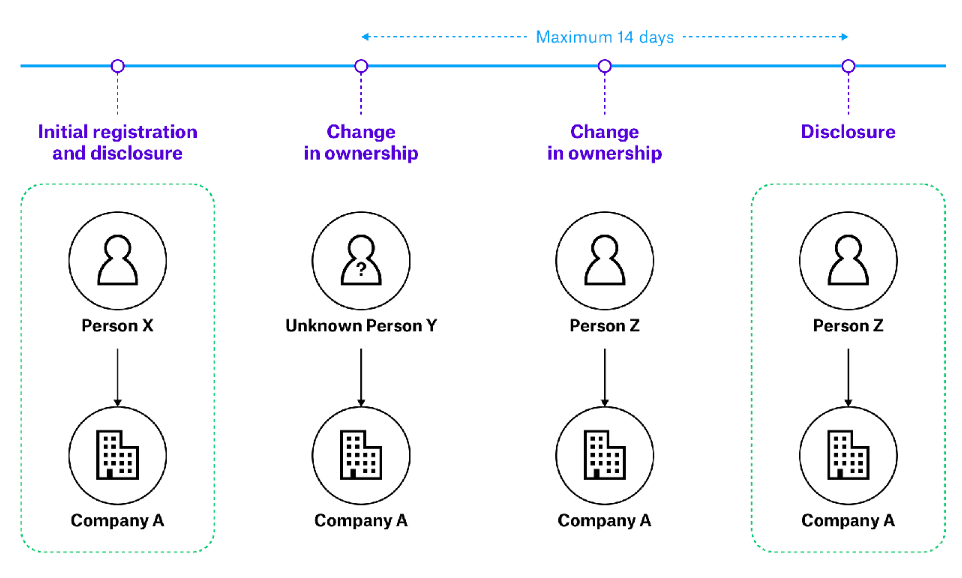

- Mandatory reporting should be a requirement of the initial registration and promptly after all subsequent changes to beneficial ownership (why all changes need to be reported is explained in Figure 1), ensuring that information is updated within a clearly defined time frame following each alteration.

- Legal obligations should mandate periodic confirmation of accuracy, occurring at least annually, such as through the submission of annual statements.

Figure 1. How loopholes can undermine BOT reporting

In this example, Company A has disclosed Person X to be its beneficial owner at initial registration. Later, Person Y replaces Person X as the company’s beneficial owner. The prescribed period for reporting changes in this jurisdiction is 14 days. Within this period, the beneficial owner of Company A changes again from Person Y to Person Z. If there is no requirement to report all changes in BO, Person Y can legally avoid disclosure – and potentially exploit this for illicit purposes – provided that Person Z is disclosed as the beneficial owner within the prescribed period of the first change in ownership. Source: Open Ownership.

Legislation should specify clearly what information should be included in a declaration, for instance:

- Sufficient details about the beneficial owner(s) to identify them

- The means through which ownership or control is held

- Details about the declaring corporate vehicle and the individual submitting the declaration

The information collected should include reliable identifiers to unambiguously identify individuals, entities and arrangements, as well as sufficient information to ensure data accuracy to a reasonable level. Information should be collected, ideally through online forms with accompanying guidance on how to complete them. Forms should be designed as a service informed by user needs to facilitate and enable compliance. Therefore, forms should be periodically reviewed and not included within the legislation itself.

Establishing the Register and Delegating Powers to Registrars

Legislation should provide the powers, mandate and responsibility to an authority to create and oversee a BO register. Most often, these authorities are corporate registries, tax authorities or financial intelligence units. Legislation should also specify how and for how long records should be kept, which should be a reasonable and specified number of years, including for dormant and dissolved corporate vehicles. Parliaments must also consider whether different authorities should oversee registers for different corporate vehicles. In this event, the law should enable sufficient coordination, cooperation and exchange of information between registers. Legislation should also place a responsibility on the registrar to ensure information is stored digitally in an organized, accessible and usable way.

"Legislation should provide the powers, mandate and responsibility to an authority to create and oversee a BO register."

Verifying Accuracy of Information

International standards require the verification of the identity and status of beneficial owners, ensuring accuracy. While specific verification methods are not usually detailed in legislation, parliaments need to empower the registrar to ensure accuracy. This typically involves powers such as requiring information, removing incorrect data, and taking action against noncompliance. Third parties, like AML-regulated entities (such as financial institutions or lawyers) can be required to play a role in verification. Legislation may also place the burden of proof of establishing that the information is accurate on those submitting the information, as done in Slovakia. There, a dedicated Registration Court has independent oversight and deals with claims of inaccurate information. In general, lawmakers should ensure appropriate oversight.

Mechanisms for Information Access

Parliaments must address how beneficial ownership information is shared and accessed in legislation, specifying who can access it (such as government agencies, the public, the media and companies), what they can view – limited to what the users need – and how they can use it. Ideally, parliamentarians should ensure the involvement of potential users in consultations. Users may require specific information, and access levels must be tailored accordingly. Similarly, legislation should ensure there are no obstacles to the integration and interoperability of BO data with other government systems, such as the public procurement electronic platforms, tax databases or trade registries. Parliaments should also thoughtfully design access provisions, ensuring their impact on the right to privacy is necessary and proportional to achieving the objectives. Privacy risks can be reduced by excluding unnecessary and sensitive information and providing a mechanism by which those who face disproportionate risk can have some or all information withheld from publication. Legislation should be supported by privacy impact assessments and include appropriate safeguards. The easiest way to ensure relevant parties have access to the data to ensure the full potential benefits of BOT are realized is by making the register freely open to the public, although this may not be possible in line with privacy and data protection requirements in every context. At a minimum, allowing access to civil society groups, activists, and the media can increase the impact of the reforms, with these actors providing more oversight than regulatory bodies alone. Broader access is more easily justified when governments pursue a broad range of objectives anchored in the public interest.

"The easiest way to ensure relevant parties have access to the data to ensure the full potential benefits of BOT are realized is by making the register freely open to the public."

Beneficial Ownership Transparency and the Right to Privacy

BO information comprises, by definition, personal information and therefore has a bearing on privacy and data protection. Beneficial owners, just like any other natural persons, have the right to privacy and data protection in most jurisdictions. Nevertheless, these are often not absolute rights. This means they can be limited in certain circumstances – for example, if it is in the general interest to do so or when it conflicts with other rights. A law that enables access to and processing of this information should therefore be necessary to achieving its specified purpose, and this should be proportional to the interference with the rights it causes.

Generally, a risk to privacy arises from information being misused for the intended purposes. Governments can take various approaches to prevent and detect misuse. Governments should have already spelled out their policy objectives in the law and various supporting policy documents, as covered above. Methods to reduce misuse include providing information to certain users with a legitimate interest, particularly where this concerns access to a large amount of information and high flexibility in how this information can be searched and used. Other measures can include registration, attestations to use the data in line with specific purposes, and data licenses. While these specific measures are not likely to be included in primary legislation, broad provisions for access or designating certain user groups as having a legitimate interest by default may be.

Often, questions around designing access provisions are oversimplified to a false dichotomy of whether information should be made public or not. This has become a particularly lively debate following the November 2022 judgment by the Court of Justice of the EU ruling that the way the EU had legislated for public access to registers was legally invalid, for instance, by not limiting the amount of information member states made public.

To maximize the impact of the reforms, all actors who can use the relevant information to further a country’s policy aims should have access to the information when needed. Governments must therefore strike a balance between the access to this information and its usability and the interference with the right to privacy this causes. Where this balance is will depend on the pursued policy aims, the domestic legal context and norms around privacy in society. Generally, implementing governments should consider how to safeguard rights to the greatest extent possible, without overly sacrificing the usefulness and usability of the BO information.

Creating Penalties for Noncompliance

Parliaments must ensure that legislation includes consequences for all forms of noncompliance, such as failure to submit, late submission, incomplete submission and incorrectly submitted information. Persistent noncompliance and other obligations related to the disclosure regime, particularly for third parties, should also be addressed. These sanctions must apply to all individuals involved in making declarations and key figures within the corporate vehicle, including beneficial owners, declarants, company officers and the declaring corporate vehicle. The responsible authorities for enforcing sanctions, including the registrar, should be clearly determined in the legislation, and the registrar should possess the capability to issue basic administrative sanctions. To be effective, sanctions, whether administrative or criminal, should be proportionate, dissuasive and enforceable. Striking a balance between financial and nonfinancial sanctions is crucial; while financial penalties should be set sufficiently high, evidence suggests that nonfinancial sanctions, such as restricting business transactions with noncompliant entities or barring them from participating in public procurement, can be more impactful in ensuring compliance.

Footnotes

[1] Note: This section is based on more extensive guidance by Open Ownership. For more detail, and for country examples, please see Favour Ime and Tymon Kiepe, Guide to Drafting Effective Legislation for Beneficial Ownership Transparency, Open Ownership, August 2024.

[2] Primary legislation sets out the framework for other laws, which in Westminster contexts is referred to as secondary legislation but can also be referred to as delegated legislation.