Beneficial ownership transparency and the United Nations Convention against Corruption: progress and recommendations

Global progress to date

Beneficial ownership transparency in the United Nations Convention against Corruption processes

As a measure to prevent the laundering of the proceeds of corruption, UNCAC States parties are committed to instituting comprehensive domestic regimes to deter and detect money laundering. The convention also emphasises that banks and other financial institutions should identify beneficial owners and maintain appropriate records. [5] To assist asset recovery, the Convention highlights the importance of financial institutions determining the identity of beneficial owners of funds deposited in high-value accounts, and to conduct enhanced due diligence of accounts of politically exposed persons (PEPs). [6]

Under the 2021 UNGASS political declaration against corruption, States parties to the UNCAC further committed to preventative measures to enhance BOT. This includes ensuring that adequate, accurate, reliable, and timely BO information is available and accessible to competent authorities. It also includes the promotion of BO disclosure and transparency through, for example, registries in line with domestic laws, and the use of guidance from anti-money laundering initiatives. [7]

Resolution 7/1, adopted at CoSP 7 (2017) calls upon States parties to take appropriate measures to promote transparency of legal persons, including by collecting information on beneficial ownership. While several other resolutions adopted at CoSP sessions underscore the importance of BOT, Open Ownership finds Resolution 9/7, adopted at CoSP9 (2021), to be a commendable step for UNCAC States parties to combat corruption with more comprehensive BOT commitments.

The resolution encourages States parties to collect and maintain BO information, and then calls upon States parties to ensure, or continue ensuring, timely and efficient access to adequate and accurate BO information on companies for their domestic authorities. There is a strong focus on ensuring the use of BO information to support asset recovery, including through international cooperation, and the use of digital technologies to exchange data.

Global progress since the 2021 United Nations General Assembly Special Session political declaration

Beyond the UNCAC, since the 2021 UNGASS political declaration there have been notable positive shifts in global standards and international commitments to BOT. At the 2nd Summit for Democracy (2022), over 35 countries restated their commitment to effectively implement international standards on BOT. This followed substantial revisions to the international Financial Action Task Force (FATF) Recommendations in 2022, which now mandate the creation of central BO registries and access to BO information by public authorities over the course of public procurement. [8]

Over 39 states have made a commitment related to beneficial ownership through their membership to the Open Government Partnership (OGP) and over 50 implementing countries of the Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative (EITI) have committed to making BO information of extractive sector companies publicly available.

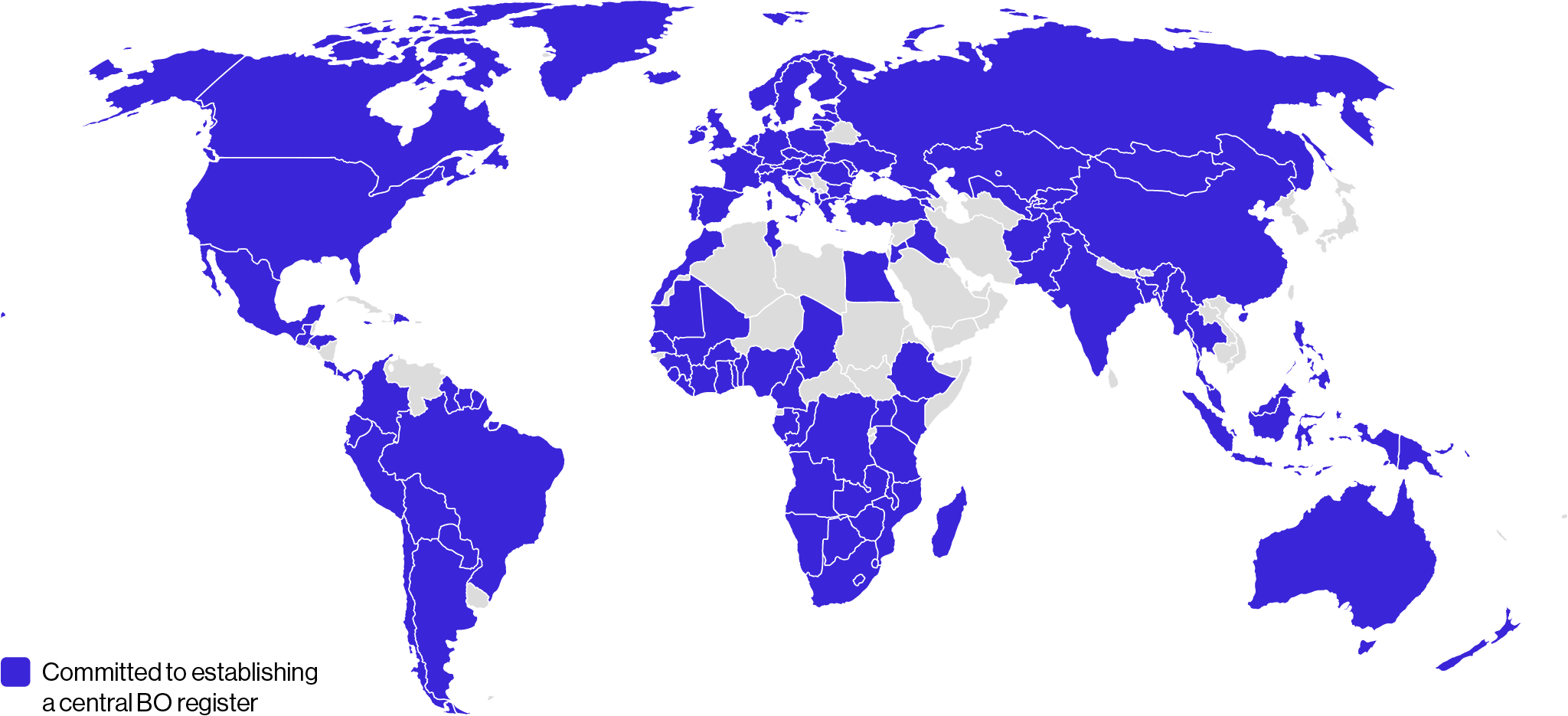

Figure 1. Countries committed to establishing a central BO register

Over 120 countries have committed to establishing central BO registers. Around 50 countries have implemented registers to date.

In total, over 120 countries are now committed to establishing central BO registers. Despite this, only around 50 countries have so far implemented registries. [9] The meaningful implementation of these commitments is exceptionally important considering the prevalence of corruption and financial crime globally, and the serious related harm to people and to the planet that ensues, for example through the rise in violence and conflict. [10]

Time and again illicit financial flows – the proceeds of corruption and other financial crimes – are moved around the world using anonymously owned companies, and the proceeds are used to undermine legitimate business environments, exert malign influence on governments’ policy-making, and advance other nefarious activities. The role of a broad range of actors – from law enforcement to companies to investigative journalists – is now widely recognised as important for effectively combating these threats.

In this context it is noteworthy that the majority of the 120 countries committed to establishing central BO registers are committed to enabling at least some information to be made publicly available. Nevertheless, the issue of whether and how the public should be able to access BO information remains high on the global policy agenda.

A 2022 decision [11] by the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU) determined that the legal approach taken in the European Union’s 5th Anti-Money Laundering Directive to justify public access to BO data did not appropriately balance privacy and transparency for the stated purposes of fighting money laundering. The decision found that public access to BO data was not sufficiently justified solely for the purpose of fighting financial crime. This judgement has underscored the importance of effectively balancing rights to privacy with the public benefits that arise from making BO information publicly available.

The judgement however recognises the legitimate right of civil society, journalists, and owners of businesses entering into transactions to access BO data to support anti-money laundering goals. This echoes the 2021 UNGASS political declaration, which underlined the important role of civil society, media and the private sector in identifying, detecting, and reporting on cases of corruption. [12] Steps are already being taken by the European parliament to safeguard access to beneficial ownership information among key actors and to strengthen verification and cross-country sharing of the information.

In this context, the global policy debate is shifting away from a simple binary of whether or not BO information should be made public. The current discussion is pragmatic — how, in law and practice, can states enable all actors with a role to play in preventing and detecting corruption to access and use BO information effectively.

Global progress to implement public beneficial ownership registers

Ukraine was the first country in the world to launch a public register of beneficial owners of corporate entities, created in 2015. In 2016, the United Kingdom (UK) became the first G20 country to implement an open and free-to-access public register of beneficial owners of UK companies. Armenia, Denmark, Latvia and Slovakia were similarly some of the first countries globally to implement public BO registers.

Across Africa, there is notable momentum towards implementing public BO registers. In 2023, Nigeria launched its public register, following Zambia and Ghana’s registers launched in 2019 and 2020, respectively. Several EITI-implementing countries have also established public BO registers for the extractive sector.

Progress is also seen in Asia, with Indonesia making its central BO register public in 2022. In Latin America, progress towards public registers is more nascent, but a recent draft Anti-Money Laundering Bill in Argentina creates scope for this to be legislated for in the future.

Notes

[5] Article 14(1)a), United Nations Convention against Corruption (United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, 2004), page 16, www.unodc.org/documents/brussels/UN_Convention_Against_Corruption.pdf.

[6] Article 52(1), United Nations Convention against Corruption (United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, 2004), page 42, www.unodc.org/documents/brussels/UN_Convention_Against_Corruption.pdf.

[7] Article 16, Resolution adopted by the General Assembly on 2 June 2021 (United Nations General Assembly, 2021), page 6, https://documents-dds-ny.un.org/doc/UNDOC/GEN/N21/138/82/PDF/N2113882.pdf?OpenElement.

[8] The FATF also permits an alternative mechanism to a central register, provided it also provides efficient (rapid and reliable) access to adequate, accurate, and up-to-date beneficial ownership information. It does not appear that any alternative mechanisms providing similar quality access to adequate, accurate and up-to-date information have been implemented to date.

[9] Open Ownership, The Open Ownership Map, 2023, https://www.openownership.org/en/map/.

[10] In 2022 the UN, EU, UK, and United States began applying sanctions on individuals, as well as entities and their subsidiaries, in reaction to Russia’s 2022 invasion of Ukraine. The UK reports that the accurate identification of beneficial owners with links to Russia has led to more than 220 individuals and entities being sanctioned by the UK since the invasion, including 12 of Russia’s leading oligarchs.

[11] Court of Justice of the European Union, “Press release No 188/22, Anti-money-laundering directive”, 22 November 2022, https://curia.europa.eu/jcms/upload/docs/application/pdf/2022-11/cp220188en.pdf.

[12] Article 21, Resolution adopted by the General Assembly on 2 June 2021 (United Nations General Assembly, 2021), page 7, https://documents-dds-ny.un.org/doc/UNDOC/GEN/N21/138/82/PDF/N2113882.pdf?OpenElement.

Next page: Looking forward: using beneficial ownership data to prevent and detect corruption