Beneficial ownership transparency in Armenia: scoping study

Beneficial ownership transparency in Armenia

In this section of the report, we outline Armenia’s current or planned BO reforms and assess these against OO’s Principles of Effective Beneficial Ownership Disclosure. For each of the nine principles, we have provided a short analysis of how Armenia’s disclosure regime is addressing the aspect identified and have provided recommendations for how the country could further strengthen its policies and processes.

Public access to a central register

OO PRINCIPLE

Data should be accessible to the public; data should be collated in a central register

- The public should have access to BO data.

- BO disclosures should be collated and held within a central register.

- Data should be accessible without barriers such as payment, identification, or registration requirements.

- Where information about certain classes of persons (e.g. minors) is exempt from publication, the exemption should be clearly defined and justified. Any case-by-case exemptions (for example, to mitigate personal safety risk) should additionally be proportionate, and fairly applied.

- In cases of publication exemptions, the public register should note that BO information is held by authorities but is exempt from publication.

Armenia should be commended for its determined efforts to produce an extensive public register, and for the rapid pace by which it has moved from making international commitments to publishing its first sets of data. A pilot disclosure regime for the few dozen firms operating in the country’s mining sector has already been implemented and the BO data submitted by these companies was published in April 2020.[7] Current plans are for Armenia to introduce similar requirements for a far broader range of industry sectors by the end of the year. The country is also developing a new software module for its central company register that will be used to store and publish companies’ BO information.

Recommendation 1: Armenia should further improve the accessibility and utility of future BO disclosures by publishing in “open data” format and enabling bulk downloads

The precise details of how Armenia will publish BO data in its forthcoming system are still being finalised and we encourage authorities to proceed with plans to ensure that the eventual system meets all characteristics of “open data”. This concept is defined by the International Open Data Charter as “digital data that is made available with the technical and legal characteristics necessary for it to be freely used, reused, and redistributed by anyone, anytime, anywhere”.[8 The main differences between the various categories of data publication are outlined in the table below:

| Closed: restricted access | Shared: public | Open: accessible to all |

|---|---|---|

| Access may be limited to law enforcement and other authorised bodies | Payment may be required to access | Free (no cost) |

|

Access may be limited to those demonstrating “legitimate interest” |

May require registration, password or authentication | Structured data |

| Data may be unstructured (e.g. paper forms, PDFs) | Open license | |

| Licence may limit use |

Armenia’s existing systems for the publication of information on companies’ legal owners fulfil most, but not all, of the characteristics of “open data”. For example, users who wish to obtain this information for an Armenia-registered company currently need to pay a small fee of approximately GBP5.00 to access the full record from the State Registry.[9] To fulfil the criteria for “open data”, the upcoming software for BO data Armenia should enable fee-free access to data that is available in a structured format (see Structured data section below).

In addition, data on legal owners is currently available on a “per-record” basis, meaning that users can only download information on one company at a time. We welcome indications from Armenia that it will enable bulk downloads when it comes to publish its full BO data in its forthcoming software. Enabling BO data to be accessed in bulk has numerous advantages, including economic ones.

Bulk downloads: creating value and increasing impact

Bulk access to BO data can facilitate creation of economic value by allowing firms to combine BO data with their own intelligence and other data sets to build innovative new products or services. For example:

- In Ukraine, the company YouControl uses open BO data from the State Enterprise Registry as a key data source for the innovative commercial due diligence tool it has developed. Their software combines the BO data together with information from multiple other data sources. YouControl then analyses the data through proprietary risk analysis tools to provide detailed commercial intelligence to investors and suppliers considering entering into business arrangements with Ukrainian entities. Their website lists several case studies where the company reports that its tools have helped identify wrongdoing and/or enabled businesses to avoid entering into suspicious commercial deals.[10]

- In the UK, Sqwyre uses data from the UK BO register to provide market intelligence services to the real estate sector. Sqwyre uses bulk data to match the names of ratepayers in local council data to their larger corporate groupings. This helps identify instances where, for example, a branded high street shop is in fact owned by, and paying rates as, a local subsidiary company. The BO data enables Sqwyre to fill in some of the gaps in their data where councils withhold ratepayer information, and to perform higher-level analysis of local economies. The end product is an assessment of how well independent businesses are doing in a specific area compared with larger corporations, and this information is then used to help advise firms on their optimal location.

Enabling bulk data downloads would help increase the number of people using Armenia’s data, and facilitate independent scrutiny of the information by allowing analysis of multiple records to identify potentially suspicious activity and/or inaccurate data submissions. Bulk downloads would also allow Armenia’s data to be pieced together more easily with information published in other jurisdictions, including with the data already available in Open Ownership’s Global Beneficial Ownership Register.[11] This, in turn, helps increase the impact of Armenia’s publications by facilitating investigator efforts to trace financial flows through the kinds of complex international BO chains that are invariably found in the largest money laundering schemes.[12]

Robust definitions

OO PRINCIPLE

BO should be clearly and robustly defined in law, with low thresholds used to determine when ownership and control is disclosed

- Robust and clear definitions of BO should cover all relevant forms of ownership and control.

- Low thresholds for triggering BO disclosure should be used so that most, or all, people with BO and control interests are included in disclosures.

- Particular consideration should be given to thresholds that apply to ownership by PEPs, with a clear definition used to determine what constitutes a PEP.

- Absolute values, rather than ranges, should be used when reporting the percentage of ownership or control that a beneficial owner has.

Armenia has two main definitions of BO within its legislation, which are outlined in the 2008 Anti-Money Laundering (AML) Law and the 2019 State Registration Law. The principle differences between these two legislative definitions are outlined in the table below. In line with best practices, Armenia’s understanding of what constitutes BO includes both elements of control (for example, if an individual is able to appoint or dismiss board members of a company) and of ownership (i.e. if an individual ultimately controls above a certain percentage of shares in the firm). The inclusion of these key elements in its BO definition will provide a solid foundation for requiring disclosure, by the end of 2020, for a broader range of firms in other sectors.

| Means of ownership or control | AML Law (2008) | State Registration Law (2019) |

|---|---|---|

| Shareholding | 20%+ of voting shares | 10% share – individually or jointly with an affiliated person |

| Voting rights | 20%+ of voting shares | "Voting stocks...granting the right to more than one vote" |

| Decision making or oversight | "exercises factual (real) control over the legal person or transaction (business relationship), and (or) for whose benefit the business relationship or transaction is being carried out." |

“[those] entitled to appoint or dismiss persons included in the management bodies of a legal person”; “member[s] of the management and (or) governing body of the given legal person”; or “entitled to otherwise predetermine the decisions of the legal person” |

| Profits | N/A | Those in receipt of 15% of company profits |

For the mining sector, a more stringent system of disclosure requirements has been applied to PEPs who are deemed a higher corruption risk due to allegations that stakes in mining firms had been illegally sold to firms controlled by PEPs after the revolution in 2018.[13] For these individuals, no threshold is in place, meaning their beneficial interests in mining firms had to be disclosed to authorities even where they controlled only a 0.01% share.

Recommendation 2: BO definitions in Armenian legislation should be harmonised as much as possible and plans made for the periodic evaluation and revision of threshold levels.

Generally, the existence of competing BO definitions in a country’s legislation can create confusion for both data users and disclosing entities about exactly what information needs to be reported to authorities. Moreover, there is a risk that some firms will seek to exploit loopholes by cherry picking those elements of the various definitions that are most favourable to them and/or using this as a legal defence if authorities seek to apply sanctions for non-compliance. Creating a unified definition in legislation, as Slovakia has done, for example, can help navigate some of these various difficulties.

When undertaking this harmonisation of BO definitions, we would generally advocate that the more comprehensive disclosure requirements be adopted wherever there is a disparity between the various laws. In Armenia’s case, this would see the application of the more robust threshold of 10% across the disclosure regime: all firms would have to declare the identity of anyone ultimately controlling a percentage of shares above this amount. Whilst there is no one-size-fits-all level for thresholds, [14] experience of other disclosure regimes suggests that figures in the range of 5-15% generally provide a good balance between obtaining data on a broad range of relevant beneficial owners, while retaining sufficiently high quality data to meet policy goals. For Armenia, we acknowledge that, at least for the first iteration of the register, there is an argument for using the 20% threshold from the AML legislation. This could facilitate more rapid adoption of reforms and fuller compliance with the economy-wide disclosure requirements among notaries and other actors that are already accustomed to working with the more long-standing definition. In either event – but especially if the higher threshold is eventually selected – we would recommend that Armenia adopt an iterative approach to its threshold setting. In practice, this means conducting periodic reviews to ensure the level selected is appropriate and enables the country to meet its policy goals from its BO disclosures. The first of these should be conducted after the first round of economy-wide disclosures have been submitted, based on an analysis of the BO information received, to determine the potential benefits and trade-offs involved in lowering the threshold. Future reviews and updates of the threshold level should also constitute an integral part of the iterative design process on which BO reforms are ideally based.

Recommendation 3: Clear guidance should be provided to disclosing entities regarding their reporting obligations for PEPs and “affiliated persons”

International definitions of PEPs commonly include not just the person directly holding political office, but also those close to them, such as their spouse and immediate family.[15] In Armenia’s case, in addition to the concept of PEPs, the country has created a category of “affiliated persons” in relation to BO. The precise scope of personal relationships that fall within the concepts of affiliated persons and PEPs should be explained clearly in guidance for those filling out BO disclosure forms. This is because a person’s control or ownership over an entity may lead to their being identified as a beneficial owner, primarily by virtue of familial and personal relationships, either because they are a PEP or because they are an “affiliated person” (or both). A clearer explanation of the precise delineation between the two concepts will help reduce accidental errors in the data disclosed by entities for those in political office and their close associates/relatives. Conducting a review of the data on the PEP and affiliated person submitted during the extractives pilot could also help assess how far disclosing entities have met the intended goals of the legislation and identify priority areas to clarify in the guidance. User forums and feedback sessions could also help highlight any particularly challenging areas for the disclosing entities and indicate where additional guidance or clarifications regarding the PEP and affiliated person disclosure processes are required.

Comprehensive coverage

OO PRINCIPLE

Disclosure should comprehensively cover all relevant types of legal entities and natural persons

- All relevant legal entities and arrangements, and all relevant natural persons (i.e. people), should be included in disclosures.

- Any exemptions of certain types of entity from the disclosure requirements (such as for listed companies) should be clearly defined and justified, and information on the ownership of such entities should be collected elsewhere with comparable levels of quality and access.

- Particular attention should be given to the disclosure requirements relating to ownership by state owned enterprises (SOEs).

Thus far, and as discussed above, Armenia has only legislated for BO disclosures in one sector.[16] However, the country is currently working on a series of further legislative reforms that will require disclosures across the economy by the end of the year. This would bring Armenia in line with the earlier commitments made to this effect within its Open Government Partnership National Action Plan for 2018-2020.

Recommendation 4: Drafting of economy-wide disclosure regulations should begin as soon as possible and aim to cover the overwhelming majority of companies registered in the country

A clear legislative strategy will be required to bring about the planned transition from requiring disclosures from one sector to creating legal obligations across all other sectors. At the time of writing, provisional plans were for a staggered introduction of BO disclosure requirements across the economy, beginning with regulated entities, followed by non-regulated commercial bodies, and finally non-commercial entities. This seems a sensible strategy. Given the anticipated several-month-long timeline for the drafting, scrutinising, and approving of legislation, Armenia should seek to initiate this process as soon as is feasible and not wait for the completion of the software system that will eventually store the full economy disclosures.

The principle of “comprehensive coverage” does not merely entail creating a register covering all industry sectors. It also means limiting, as far as possible, the introduction of exemptions from disclosure requirements for certain classes of company or legal vehicle.[17] Such exemptions, often introduced on the grounds of privacy concerns or because certain legal structures are deemed low risk, may limit the impacts of public registers by encouraging illicit finance to switch into those precise vehicles excluded from disclosure requirements (see case study box). When drafting the legislation for the next round of disclosures, Armenia should make efforts to adhere to the principle of comprehensive coverage as much as possible.

Case study: the risks of disclosure exemptions in the UK

Experience from other international contexts highlight the potentially detrimental effects of excluding certain classes of company from the requirement to disclose their beneficial owners.

When the UK, for example, first created its regime for declaring beneficial owners (as part of its “Persons of Significant Control” register), obligations to disclose were not applied to Scottish Limited Partnerships (SLPs). As a result, these formerly obscure legal vehicles became popular with international criminals seeking to hide and/or store illicit earnings, as they provided higher levels of anonymity compared to standard UK corporations. Registrations of this firm type increased, and the BO profile was later revealed to be rather different from other UK firms: over 40% of SLPs had a BO linked to a post-Soviet country compared to only 0.15% for more standard corporation types in England and Wales.[18]

Following the expansion of BO disclosure requirements to cover SLPs in 2017, the number of incorporations of this type of legal vehicle fell to its lowest level in seven years. At the same time, there was an unexplained rise in the creation of Northern Irish Partnerships – a different sort of corporate structure that was also excluded from BO reporting requirements.[19]

These shifting trends in company creation that closely followed the related alterations to UK disclosure obligations, illustrate the importance of allowing, at most, only very limited exemptions from requirements to report beneficial owners.

Structured data

OO PRINCIPLE

Data should be structured and interoperable

- BO data should be available as structured data, with each declaration conforming to a specified data model or template.

- Data should be available digitally, including in a machine readable format.

- Data should be available in bulk as well as on a per record basis.

As part of its BO disclosure pilot for companies in the mining sector, Armenia published BO data from these firms in spring 2020. To expedite data collection and publication for the pilot, Armenia opted to collect BO information via paper forms, which have then been converted into PDF format for publication. As such, these initial disclosures are not available in structured data format.[20] However, in May 2020, the country contracted a private sector provider to develop software that will enable publication of structured data and OO will continue to advise the contractor and implementing agencies to support the use of the BODS within the new software. Armenia also remains committed to structuring its data in line with the statement model outlined in the BODS [21] a digital format that enables BO data to be published in a machine-readable form that can be easily understood and connected with other datasets.[22]

Recommendation 5: Armenia should use an agile development methodology for its BO software, using mining sector disclosures to test the system’s handling of structured data

The development of the software system for storing and publishing BO data in a structured format is ongoing. Once available, the data from the mining sector disclosures should be used as test data that will help assess whether the software is adequately equipped to deal with complex and fringe cases of BO structures. Using the mining disclosures as test data will have the additional benefit of converting these early submissions into structured data that can then be linked with data from other international registers. More broadly, we would recommend using an “agile” methodology for the BO software development, focusing up-front effort on user research and design, prototyping potential solutions, and building and testing small advancements in the project in stages. This should be done repeatedly and cyclically so that learning can be rapidly ploughed back into development. In this way an initial version of the software can be deployed rapidly, but will remain in a rolling state of development and testing. This will help ensure it can be fitted to real use, and will make it easier to modify the software to meet future BO requirements for companies in other sectors of the economy. This is important, since the legal framework for BO disclosures of non-extractives companies is still under development, and the disclosure requirements may differ (e.g. in terms of information fields required, level of detail on affiliated persons, and ownership structures).

Sufficient detail

OO PRINCIPLE

BO disclosures should contain sufficient detail to allow users to understand and use the data

- Key information should be included about the beneficial owner, the disclosing company, and the means through which ownership or control is held.

- Clear identifiers should be used for people and companies.

- PEPs should be clearly identified within the data.

- Where BO is held indirectly through multiple legal entities, sufficient information should be published to understand full ownership chains.

Armenia has committed to implement the BODS, [23] which is a helpful guide as to an appropriate level of detail that should be collected and published about the declaring company, intermediate companies, and natural persons. The level of detail should be enough to meet the internal requirements of government, authorities and enforcement agencies, and citizens. It should support the clear, unambiguous identification of companies and individuals, allow them to be contacted where necessary, allow links to be drawn with information elsewhere, and provide information required for demographic, law-enforcement, economic, and sectoral analysis. Detailed information should also be collected about the means via which ownership or control are exercised.

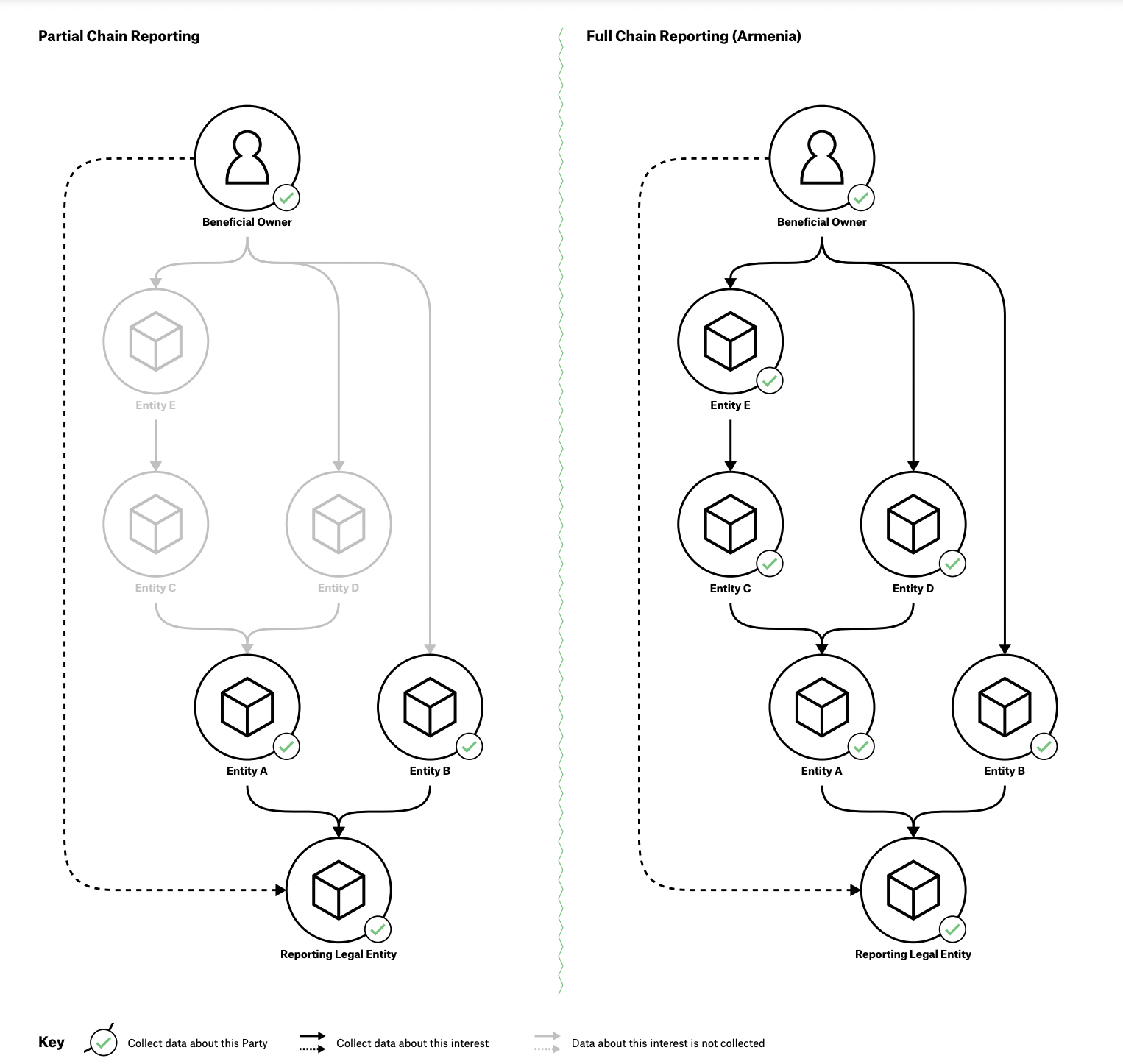

Countries have adopted different approaches regarding how much information they require to be disclosed about the intermediary companies and entities through which BO or control may be exerted. Armenia’s legislation for its extractives pilot obliges companies to disclose information on each intermediate company in the chain between the reporting entity and (a) each beneficial owner, and (b) each publicly listed company with a 10% stake or more in the reporting entity. This approach, illustrated on the right of the figure below, is more comprehensive than a “partial chain” approach, such as that on the left, applied in other international contexts such as the UK.

Armenia adopted this “full chain” approach for its mining sector due to the perceived high levels of corruption risk traditionally associated with resource extraction. This approach meets our minimum advised level for disclosure of information about ownership chains and provides valuable additional detail on the intermediary entities in these chains. Such information will likely increase the anti-corruption impact of BO disclosure by enabling a more granular understanding of how ownership or control is exerted. This also has the advantage of providing more details that can be analysed and verified after publication, helping to drive up overall data quality as well as to identify potentially suspicious disclosures in the register.

Figure 3. Ownership chain reporting requirements

Recommendation 6: In the first iteration of the economy-wide register, reporting requirements should be made simpler, requiring only data submissions for the beneficial owners and first level entities in an ownership chain.

Discussions of plans for disclosure requirements for the non-extractive sectors are ongoing, but indications are that Armenia will be somewhat reducing the scope of reporting obligations for less politically sensitive sectors. Specifically, initial plans are to require firms in other sectors to report only the first level intermediary, rather than the details of all companies in the ownership chain. This seems a sensible approach, at least for the first round of disclosures, and would fall more closely in-line with requirements in other international contexts.

The application of “full chain” reporting across all sectors is complicated by the additional difficulties companies face in accurately reporting information pertaining to all entities in the ownership chain, especially where these cover multiple jurisdictions. For complex ownership structures in the mining sector pilot, for example, firms have needed to submit a large quantity of forms for each declaration. Similarly, such disclosure requirements may mean that intermediate companies may be disclosed in multiple declarations, which in turn increases risks that information submitted by different entities will not precisely tally. Even within the small sample of firms involved in its pilot programme, there have been some suggestions of difficulties, with some firms reportedly submitting erroneous information due to not fully understanding the requirements. Whilst such discrepancies between different submissions could eventually serve as a means to crosscheck and verify data submissions, this would require a sophisticated data verification system of the sort that Armenia is yet to develop.

For BO data, as with many other data gathering exercises, there is likely to be a trade-off between collecting more data that is less accurate, and collecting less data that is more accurate. For its initial iteration of its economy-wide register, we would recommend that Armenia concentrate on gathering the higher quality data that would likely emerge from a more limited “partial-chain” reporting requirement. Once the first set of data has been gathered, the disclosures can then be evaluated with a view to understanding whether a more comprehensive approach would be useful. At this stage, online BO data submission forms are due to have replaced the current paper versions, improving the user experience of disclosing data and potentially facilitating the introduction of more comprehensive reporting requirements.

Recommendation 7: Unique IDs (including country-level IDs) for people and entities should be collected and published

Within its systems for extractive industry disclosures, Armenia has already integrated company identifiers that are unique within the country and thus clearly separate the records of any company operational within Armenia. To ensure that Armenia’s data for its full economy disclosures can be integrated with the data from other international registers, we recommend that the country appends country-level information to its Unique Identifiers (UIDs). Country-level IDs eliminate the possibility of ending up with two companies in separate countries having the same UID.[24] To this end, we advise that the country of registration and registration number should be collected for all registered companies (foreign and domestic) that are included in a given disclosure. These registration numbers should be validated against the records of the registration where these are available.

In particular, when publishing disclosures, company numbers should be accompanied by a reference to the registration authority. For this purpose we recommend the use of org-id.guide, which lists reference IDs for registration authorities; for example, the Armenian State register can be referenced using “AM-SRALE”.[25] Therefore, the company VXSoft is uniquely identified by the code: AM-SRALE-286.110.766087 [26]. Since the state registry also uses “Z-codes”[27] to identify companies, we recommend that these also be published.

On the issue of unique identification of individuals, Armenia already collects details of an individual’s ID documents. If people’s ID numbers are already in the public domain, then there is no reason to exclude them from published records of BO. However, data privacy laws may understandably proscribe such publication. Ultimately the aim is that the published data should allow users to confidently determine whether one person is a beneficial owner of more than one company in a jurisdiction. Since ID numbers will be used internally in the system for disambiguation, it should be possible to generate a unique internal ID for individuals – akin to the Z-code for companies in the state registry. This can then be published so that people’s records are not duplicated if they are related to multiple companies.

Verified data

OO PRINCIPLE

Measures should be taken to verify the data

- When the data is submitted, checks should be made to ensure values conform to known and expected patterns.

- Where possible, key information should be cross-checked against existing authoritative systems and other government registers.

- Supporting evidence should be required to enable details to be checked against original documents.

- Measures should be taken to verify the identity of the person making the disclosure.

- After data has been submitted, it should be checked to identify potential errors, inconsistencies, and outdated entries, using a risk based approach where appropriate, requiring updates to the data where necessary.

- Mechanisms should be in place to raise red flags, both by requiring entities dealing with BO data to report discrepancies and by setting up systems to detect suspicious patterns.

Discussions over verification systems in Armenia for BO data submitted remain in their early stages. The first firms submitting such information – from the mining sector – have done so via paper forms, meaning that it has not been possible to conduct the kind of automated checks which can be applied to structured and machine readable data. Structured BO data is not currently available in Armenia, but will be a feature of their BO software which is under development and expected to be launched in the latter part of 2020. Though no automated checks on BO data have been conducted, the publication of the mining sector disclosures has enabled a degree of external scrutiny and manual checking of the information submitted. Several civil society organisations and investigative journalists, for example, have already produced analysis pieces on the published data for the mining sector and highlighted several disclosures they deem problematic.

Recommendation 8: Plans should be created for future enhancement and expansion of data verification systems in the forthcoming electronic register

Data verification can take place either at the point of submission of BO data or after its publication. A high level of automated “point of submission” checks will likely not prove feasible to incorporate within the initial version of the Armenian BO software (due to be released in the coming months), but systems enabling verification checks should be incorporated in the next iteration.[28] At a minimum, Armenia’s BO software should enable the cross-checking of information regarding domestically registered firms, such as the company number, with the State Registry (though a more deeply integrated system would be preferable). For foreign companies, it may not be feasible to check company numbers against foreign registries in all cases due to the legal and technical difficulties associated with establishing systems for automatic data sharing between countries. However, Armenia should still collect and publish these foreign company numbers, as they enable a wide range of users, from law enforcement to civil society, to conduct their own additional checks when they suspect wrongdoing.

A broad range of potential further improvements to Armenia’s early verification systems could be considered prior to the next iteration of its BO software. Many of the key considerations are outlined in Open Ownership’s policy briefing on this topic [29] and a thorough analysis of the upcoming data disclosures would help identify especially problematic areas of data quality. Open Ownership will continue to work with Armenian government bodies to help them think through options for future enhancements to the verification systems once the initial software becomes available.

Recommendation 9: A feedback mechanism should be incorporated into the public register that allows all users to report suspected inaccuracies

Armenia’s commitment to making its BO data public can assist the verification process by increasing numbers of data users that, in turn, drives up the likelihood of inconsistencies or potential wrongdoing being identified.[30] However, for this to work effectively as a verification measure, Armenia would benefit from creating a feedback mechanism to allow private sector actors, the public, and CSOs to report inaccuracies in data published in the BO software. This can help users draw authorities’ attention to problematic areas of the data, such as highlighting potential indicators of corruption or instances in which it appears that disclosing entities have not fully complied with their regulatory obligations. Such a mechanism exists within the UK’s register, for example, and is in fact the country’s main tool for post-submission verification. Through this “report it now” tool, over 77,000 suspected discrepancies in BO data were brought to UK authorities’ attention during 2018/19.[31] Usage of this functionality would likely be lower in the early iterations of the Armenian register due to the smaller number of companies registered there than in the UK. Adopting a risk-based approach to investigating the discrepancies reported (for example, by prioritising firms in sectors associated with high corruption risks or those that have been subject of multiple user error reports) would help limit the amount of state resources required to examine the errors reported.

Up-to-date and auditable data

OO PRINCIPLE

Data should be kept up to date and historical records maintained

- Initial registration and subsequent changes to BO should be submitted in a timely manner, with information updated within a short, defined time period after changes occur.

- Data should be confirmed as correct on an annual basis.

- All changes in BO should be reported.

- An auditable record of the BO of companies should be created by dating declarations and storing historical records.

Armenia published its first set of BO data in April 2020 and firms are both obliged to inform authorities of future changes to their BO structures and to reconfirm their BO information on an annual basis. As only an initial round of BO disclosures has thus far been submitted, the country has no historic BO data that it could publish. However, in recent discussions with the BO software developer, it appears that plans are to make dated declarations and historical BO data publicly available within Armenia’s upcoming system. This would follow the procedure for historical data on the legal owners of firms, where the State Registry publishes the names of all current shareholders and directors, alongside those of its previous owners and the date on which the individuals began and ceased their relationship with that company.

Recommendation 10: Armenia should retain and publish information regarding changes in a company’s beneficial owners

With the exception of privacy redactions, we would advocate that BO data should be kept and published for at least the lifetime of a company, and ideally for several decades after its dissolution.This means that when changes occur to BO, the previous entries that have been made to the register should be retained and remain publicly available as historical data.[32] In the UK, for instance, company records are kept for a minimum of 20 years after their dissolution and, at this stage, authorities have the option to decide to apply selection criteria by which to archive some of the less useful data (for example, by maintaining only the records of companies over a certain size).[33] Historic BO information is of vital importance for CSOs, journalists, and criminal investigators seeking to trace financial flows and prosecute money laundering and corruption cases that involve hidden BO arrangements. Long-term storage of such data is key as the complexity of these cases, and the need to obtain supporting information from other jurisdictions, means that investigations can last years before being brought to trial.

Recommendation 11: The start date on which BO arrangements began should be included in future declarations, and this field should be made mandatory in Armenia’s software

For the investigative purposes noted above, it is important for users of BO registers to have access to the date on which a particular BO relationship began and/or ceased. Making this field mandatory in the software would mean that firms will be obliged to provide dates in order to proceed to the next section of the form. However, in recognition that firms with international BO structures may face greater difficulties in obtaining documentation to confirm such information, users could also be given the option to enter an approximate date (for example, the year and/or month, rather than the precise day) on which the BO relationship began. Several firms faced such issues in the mining sector pilot, but the paper disclosure form provided some flexibility in the date field that may not otherwise be available in an electronic version. Requirements for firms to inform authorities of alterations to their profile of beneficial owners within weeks of any changes should also make identifying the start/cessation date for a BO relationship easier in future disclosure rounds.

Sanctions and enforcement

OO PRINCIPLE

Adequate sanctions and enforcement should exist for non-compliance

- Effective, proportionate, and dissuasive sanctions should exist for non-compliance with disclosure requirements, including for non-submission, late submission, incomplete submission, or false submission.

- Sanctions should be considered that cover the person making the declaration, the beneficial owner, registered officers of the company, and the company making the declaration.

- Sanctions should include both monetary and non-monetary penalties.

- Relevant agencies should be empowered and resourced to enforce the sanctions that exist for non-compliance.

For Armenia’s mining sector disclosure pilot, there has been a clear enforcement mechanism in place: the Ministry for Territorial Administration and Infrastructure – the body in charge of Armenia’s mining licensing – can suspend a firm’s extraction or exploration licence if it fails to report its BO information accurately and in full. Beyond this formal mechanism, mining firms have been driven to comply by high levels of scrutiny and pressure on their operations from civil society organisations. As a result, several firms submitted more BO data and documentation as part of their disclosures than was strictly required to comply with local legislation. This situation is unlikely to be replicated for the disclosures across the broader economy.

Recommendation 12: Armenia should develop an effective sanctions regime to apply to non-extractive sector firms that fail to comply with BO disclosure requirements

Introducing an effective sanctions regime for BO data would involve ensuring: a) that adequate sanctions exist in law, perhaps by extending existing legislation on companies’ obligations to submit information to the State Registry; b) that agencies have a legal mandate to issue sanctions; and c) that the sanctioning body has sufficient capacity and resources to verify disclosures and to identify where a given company has not fulfilled its legal obligations.

Thus far, the debate in Armenia over sanctions for non-extractive firms appears to have focused largely on which agency or agencies would be responsible for investigating potential violations and issuing sanctions. One potential option would be for the State Registry, the agency that receives and stores company and BO data, to be awarded these powers. However, this would require not only a change in the legislation, but also a substantial change in the institutional purpose and functions of the Registry, transforming it from a purely administrative entity to one with enforcement and/or investigative functions. In other countries, it is the Ministry of Justice that has responsibility for the investigation and application of sanctions of firms that do not fulfil their BO reporting obligations. Whichever entity ultimately gains this responsibility, having a formal and enforceable sanctions regime will be especially important, given that CSO pressure to comply with the legislation is likely to be significantly lower for firms outside of the mining sector.

Footnotes

[7] PDFs of the disclosures (in Armenian) are available here: https://www.eiti.am/hy/%D4%BB%D5%8D-%D5%B0%D5%A1%D5%B5%D5%BF%D5%A1%D6%80%D5%A1%D6%80%D5%A1%D5%A3%D5%A5%D6%80/?tab=88.

[8] Open Data Charter, “Principles”. Available at: https://opendatacharter.net/principles/ [Accessed 6 August 2020].

[9] Users can access a limited summary of information on companies without paying this fee.

[10] YouControl, “Case studies”. Available at: https://youcontrol.com.ua/en/cases/ [Accessed 7 August 2020].

[11] Open Ownership, “Register”. Available at: https://register.openownership.org/ [Accessed 6 August 2020].

[12] The World Bank, “The Puppet Masters”. Available at: https://star.worldbank.org/sites/star/files/puppetmastersv1.pdf [Accessed 23 June 2020].

[13] For more on these allegations, see for example: https://arminfo.info/full_news.php?id=51522&lang=3

[14] There is no generally accepted optimal level for setting thresholds of BO, not least because any threshold can be “gamed” (e.g. if the level is set at 10% then an individual can limit their stake to 9.999% to avoid the disclosure requirements). The FATF has not recommended a specific threshold, but elected to explain the concept using a 25% threshold in its worked example. Many countries have opted for lower thresholds in order to ensure the disclosures capture a broader number of key beneficial owners of enterprises.

[15] See, for example, the United Nations Convention Against Corruption, Article 52(1), https://www.unodc.org/documents/brussels/UN_Convention_Against_Corruption.pdf.

[16] One legislative assembly member has pushed for laws requiring disclosures from energy sector firms, but the MoJ has requested to hold back the date at which the legislation comes into force. The aim of this delay is to allow authorities to improve data collection processes and publication systems based on the learnings from the extractives pilot.

[17] In other areas of regulations on company activity, there are differences between types of legal vehicles. For example, company registration procedures are notably different depending on whether the entity involved is a Limited Liability Company as opposed to a Joint Venture.

[18] Global Witness, “Three ways the UK’s register of the real owners of companies is already proving its worth”. 24 July 2018. Available at: https://www.globalwitness.org/en/blog/three-ways-uks-register-real-owners-companies-already-proving-its-worth/ [Accessed 6 August 2020].

[19] Global Witness, “The companies we keep”. Available at: https://www.globalwitness.org/en/campaigns/corruption-and-money-laundering/anonymous-company-owners/companies-we-keep/ [Accessed 6 August 2020].

[20] Structured data means the data will be made available in an electronic format with all relevant information regarding each beneficial owner (e.g. name, address, nature of their relationship with the declaring entity, etc.) separated out into different fields within the software. This is important, as it more easily enables automatic checks on the submitted data to ensure the data appears in the correct format and is, at the very least, plausible.

[21] For further details on our data standard, please visit: https://standard.openownership.org

[22] Note for technical implementers: the existing company data on Armenia’s e-register is available on a per-record basis in a structured form in XML format. To be fully BODS compliant, the BO data needs to be in JSON format. Publishing the BO data as JSON means that developers and those analysing the data can make use of validation and processing tools that handle BODS data. If, however, technical architecture and related considerations make publishing in JSON problematic initially, an interim solution would be to publish in XML, which maps cleanly on to the BODS data schema. Later iterations of the country’s BO systems could then involve a shift from XML to JSON.

[23] Open Ownership, Beneficial Ownership Data Standard, “EntityStatement”. Available at: http://standard.openownership.org/en/latest/schema/reference.html#entitystatement [Accessed 6 August 2020].

[24] UID duplication has not proved a significant issue for the EITI disclosures as there are only a small number of foreign firms operating in the sector, and the plans for publication do not involve data in machine-readable format.

[25] org-id.guide, “State Register Agency of Legal Entities of Armenia”. Available at: http://org-id.guide/list/AM-SRALE [Accessed 6 August 2020].

[26] Electronic Register, “VXSOFT LLC - VXSOFT LLC”. Available at: https://www.e-register.am/en/companies/1194172. [Accessed 6 August 2020]. This assumes that the company number - 286.110.766087 - is unique and persistent. That is: only this company has this number, and the number will not change over time or due to any features of the company changing.

[27] Z-codes are internal reference numbers generated for use in Armenia’s computer systems. They are separate from the registered company number and are used to link full records about firms and their history (for example, in cases where an original company split off into different parts).

[28] At the time of writing, some “point of submission” checks were planned to be incorporated into Armenia’s upcoming BO software release.

[29] Open Ownership, “Verification Briefing”. May 2020. Available at: https://www.openownership.org/uploads/OpenOwnership%20Verification%20Briefing.pdf [Accessed 6 August 2020].

[30] Open Ownership, “Briefing: The case for beneficial ownership as open data”. Available at: https://www.openownership.org/uploads/briefing-on-beneficial-ownership-as-open-data.pdf [Accessed 6 August 2020].

[31] Companies House, “Annual Report and Accounts 2018/19”. Available at: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/822078/Companies_House_Annual_Report_2019__web_.pdf[Accessed 6 August 2020].

[32] At the time of writing, Armenia planned to store and publish all changes in BO data submitted for mining sector firms since February 2020.

[33] The National Archives, “Operational Selection Policy OSP 25 ”. May 2016. Available at: https://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/documents/osp25-regulation-of-companies-final.pdf [Accessed 23 June 2020].