Beneficial ownership transparency of trusts in South Africa

Considerations for implementing beneficial ownership transparency of trusts reform

Despite a relatively clear understanding in South African jurisprudence of the roles of the different parties to a trust, there remains a high level of ambiguity about the legal nature of trusts. The result of this uncertainty is that there is a significant discrepancy between the legal theory and the practical application of trusts. [74] In theory, trusts are not legal persons, but in practice, they are often treated as such. [75] There is also no uniform acceptance in South African law about who the legal subject (the natural or juristic persons) of the trust is. [76] As a result, identifying the beneficial owner of a trust is not straightforward in law or in practice.

The intricacies of trust law and the interaction between those intricacies and BOT considerations will be discussed in more detail below. Nonetheless, it is important to note the complexity of trusts, as this complexity has a significant impact on the application and interpretation of BOT.

The beneficial ownership transparency of trusts and the Open Ownership Principles

Establishing an effective BOT of trusts regime could help accountable institutions meet the legal requirements in FICA, and will likely contribute to South Africa’s policy aims stated in the National Development Plan and the NACS objectives. However, it is critical that the correct narrative regarding the link between the BOT of trusts and anti-corruption, tax evasion, and countering IFFs is established. Bringing BOT into the mainstream political discourse in South Africa will likely create political pressure to implement reforms with more urgency.

Public sector corruption remains a major risk to economic growth in South Africa, and policymakers need to carefully consider how trusts are abused in public procurement processes and what steps can be taken to prevent such abuse. This consideration is of particular importance in relation to excluding identified individuals from doing business with the state, as trusts are an easy way to obscure the identity of such individuals.

The OO Principles are a useful framework for providing insights into South Africa’s BOT of trusts regime design. This section will use this framework to discuss the various elements of South Africa’s current and future BOT of trusts regime and identify the key considerations in relation to each of the nine principles, first by framing the principle as defined by Open Ownership, then by discussing the current situation in South Africa as measured against the principle. The following section will discuss additional considerations applicable to the BOT of trusts.

Definition

Beneficial ownership should be clearly and robustly defined in law. In the context of trusts, the definition of beneficial owners of trusts should be comprehensive enough to include all parties to a trust within its scope – settlor(s), trustee(s), and beneficiaries or class(es) of beneficiaries, as well as any natural person exercising control over the trusts, for example, through a chain of control/ownership or through a nominee arrangement. [77]

Discussion

As discussed above, the definition of beneficial ownership as per FICA does not adequately cover the beneficial ownership of trusts. The implication of this gap in legislation essentially means that there is no robust definition in South African trust law that states that a natural person should be identified as the beneficial owner of the trust, or that the settlor(s), trustee(s), or beneficiaries or classes of beneficiaries should be registered as the beneficial owners of the trust. Additionally, there is no provision made in law for registering any additional natural persons not captured in the trust deed that may exercise ultimate effective control over the trust, or ultimately benefit from the trust. The beneficial ownership of trusts should cover:

- founder(s);

- trustee(s);

- administrator(s) of the trust (where different from the trustee);

- (discretionary) beneficiary/ies and class(es) of beneficiaries;

- any other natural person exercising ultimate effective control over or benefiting from the trust (including through a chain of control/ownership or through a nominee arrangement).

Key considerations

- Agree and adopt a legal definition of the beneficial ownership of trusts, which should cover all the natural persons who are party to a trust. This should include the founder(s); trustee(s); administrator(s) of the trust (where different from the trustee); (discretionary) beneficiary/ies and class(es) of beneficiaries; and any other natural person exercising ultimate effective control over or benefiting from the trust (including through a chain of control/ownership or through a nominee arrangement).

- Consider adopting explicit definitions for the legitimate purposes of trusts, which will empower financial institutions and designated non-financial businesses and professions (DNFBPs) to identify any transactions that fall outside the regular use of trusts.

Coverage

The data collected for purposes of establishing a BO registry should comprehensively cover all relevant types of legal arrangements. The minimum requirement should be to maintain adequate, accurate, and up-to-date BO information of trusts. However, ideally, South Africa’s disclosure regime should comprehensively cover both domestic law trusts and foreign law trusts that have any connection with South Africa. [78] “Any connection” should cover:

- the trust being formed under the laws of the jurisdiction;

- any party to the trust being resident in the jurisdiction, including nominees or anybody else who administrates the trust;

- any trust assets (e.g. bank accounts) being located in the jurisdiction;

- any service providers to the trust being based in the jurisdiction;

- any trust that has a tax implication or that is used to conduct business in South Africa.

Additionally, all types of trusts should be included in the disclosure regime. Where privacy laws, risk assessments, or other considerations warrant exclusions of specific types of trusts (e.g. special trusts) or groups of people (e.g. minors) from disclosure requirements, those exemptions should be clearly defined and publicly justified. [79]

Land rehabilitation trusts and broad-based black economic empowerment trusts are unique to South African law, and they are intended to contribute to the achievement of specific developmental goals. When considering the scope of the BOT regime, it is critical that policymakers take into account the special conditions associated with these trusts.

As mentioned earlier in this document, the FATF is currently revising Recommendation 25, which may have an impact on how countries are expected to define which entities are to be covered. The impact of potential amendments on the regulation of trusts registered in foreign jurisdictions should be monitored closely so that South Africa’s reforms comply with anticipated future requirements.

Discussion

According to the TPCA, all trust deeds must be lodged and registered with the relevant Master of the High Court. As such, the relevant authorities already have the necessary information on all domestically registered trusts, but the challenge remains with adequate, accurate, and up-to-date information. Any amendments to the trust deed or in the trustees of the trust should be registered with the Master, which, in theory, means that the information should be adequate, accurate, and up to date. [80] There is currently no requirement that the parties to a foreign law trust with ties to South Africa (as trustees or beneficiaries) must be registered.

However, as various stakeholders noted, capacity issues at the Masters’ Office and poor enforcement mechanisms for self-reporting requirements mean that the information is not always accurate and up to date. Improving the accuracy and timeliness of information should be front of mind when implementing reforms, which could be achieved through interventions, such as stricter sanctions for noncompliance (discussed in more detail below); enforceability of those sanctions; and improving the ease of updating information.

Policymakers have to consider the roles of the various types of trusts when defining the exemptions to disclosure requirements. It would be, for example, acceptable to exclude both Special Trust Type A and B, taking into account the vulnerability of the beneficiaries such trusts are intended to protect. Furthermore, risk assessments should be conducted on the various trust types to determine whether special disclosure requirements should be imposed on specific trusts.

Key considerations

- Conduct a risk assessment to identify types of trusts that might be exempted from BO reporting requirements, which may include Special Trust Type A and B. If such exemptions are granted, clear justification for the exemptions must be published.

- Additionally, the risk assessment should identify any types of trusts that create a higher risk of abuse, and special BO reporting conditions for such trusts should be considered.

Detail

South Africa’s beneficial ownership of trusts disclosure regime should require the collection of a sufficient level of detail that allows users to understand and use the data, and to enable its accuracy to be verified to a reasonable level. This means collecting information on the trust itself; the natural persons who are beneficial owners; and any legal arrangements or entities that are in the ownership chain of the trust. [81] The information collected should empower data users to understand the ownership chain of a trust, even if such ownership is held in complex arrangements and across multiple jurisdictions.

Discussion

When designing South Africa’s disclosure regime, policymakers should require sufficient information to identify all the natural persons ultimately exercising effective control over the trust. In all cases, this should include the identification documents of the natural persons that are party to the trust, and the company information of any legal entities in the ownership chain. The following is not a comprehensive list, but are important aspects to note:

- Information on the trust: Currently, the founder of the trust must provide the trust name; asset location; whether the source of funds is from a Road Accident Fund claim; and whether the trust is set up in accordance with a court order. [82] The trust deed must also be registered with the Master’s Office, and it must identify the founder, trust assets, trustees, and beneficiaries. [83] The trust assets are thus identified in the trust deed, which is a private document. Currently, there is no requirement that additional documents, such as the letter of wishes, must be registered.

- Information on beneficial owners: During the registration of the trust, the name, identity number (accompanied by certified copies of identity documents), and the contact details of the founder, trustees, and beneficiaries must be provided. Should a legal entity be a party to the trust, the same information of the natural person representing the organisation and the registration details (company or trust registration number) must also be provided. [84]

- Where the beneficiaries are a class of beneficiaries, sufficient detail should be provided to ensure that the class of beneficiaries is easily identifiable.

- Implementers should give consideration as to what information they should capture in the event a beneficiary is a minor or mentally incapacitated. For example, the name and identity number of the guardian could be captured. Whilst POPIA states that the information of minors may be processed where it is necessary to exercise a right, policymakers should consider whether to explicitly identify what information to capture when beneficiaries are minors or mentally incapacitated.

- Auditor/accountant information: Where the trust deed requires the use of an auditor or accountant, or where the trustees elect one to manage the accounting records and financial statements of the trust (required for public benefit trusts), the auditor or accountant must provide their identity number, registration number, and accreditation body during the registration of the trust. [85]

In theory, the information required during the registration of the trust should, thus, provide sufficient data for a user to understand and use the data. However, there are significant gaps that should be addressed:

- The trust assets are only identified in the trust deed, which is an accompanying private document to which investigators may not have access. The details of the trust assets (within reasonable limitations) at the time of registration should be included in the registration form.

- The letter of wishes can have a significant impact on who exercises effective ultimate control over a trust. Any additional trust documentation that impacts the workings of a trust and who controls it should be registered with the trust.

Key considerations

- Clearly define, in legislation, which data fields will need to be disclosed to authorities for all of the following: 1) the trust; 2) the beneficial owners; and 3) the corporate trustees or other legal entities involved in the ownership structure, and what events should trigger the requirement for a disclosure.

- Determine how additional documents, such as the trust deed and identity documents, are to be disclosed, and what information from such documents should be disclosed.

Central register

Lessons from the implementation of BOT for legal entities in other jurisdictions show that central registers are the most effective approach to ensuring accurate, adequate, and up-to-date information. [86] In contrast to an approach where, for example, accountable institutions hold the information, having central registers also avoids tipping off the subjects of investigation; enables proactive investigations and bulk analysis by competent authorities; and facilitates compliance. In a similar vein, South Africa should establish a central register to collate information on the beneficial ownership of trusts in which data is stored in a standardised format. [87]

Discussion

South Africa has a significant advantage in establishing a central register, as trusts must be registered with the Master’s Office, which stores such data, and therefore already has a de facto central register. The Master’s Office provides access to information on the trustees of a trust only, available to the public on the Integrated Case Management System (ICMS) Web Portal. [88] Additionally, the Companies and Intellectual Property Commission’s (CIPC) BizPortal service provides public access to limited information on public and private companies. As such, South Africa possesses some fundamental aspects of a central register that can be leveraged to establish a beneficial ownership of trusts database.

However, stakeholders raised doubts about which body should be the custodian of such a register. Whilst the Master’s Office might seem like the obvious choice, the Master’s Office’s institutional framework was designed with its mandate of protecting beneficiaries’ interest and not to manage an information database, nor to enforce compliance with disclosure requirements. Nonetheless, a custodian that is a different body than the Master’s Office will create legal and data management risks that can be best avoided by capacitating the Master’s Office with the resources required to manage a central register.

Key considerations

- South African policymakers will have to make decisions about whether to create a centralised register for trusts, and whether to do so by requiring financial institutions and DNFBPs to collect and store this information.

- If establishing a central register, decide who the registrar will be.

- Should the registrar be the Master’s Office, develop a plan for using the records of the Master’s Office as a central register of information on the beneficial ownership of trusts. This plan should include details on the mandate of the Master’s Office as the custodian of the information, the functional and technical requirements, and budgetary implications for modernising current records into a usable register.

Access

Reasonable accommodations should be made to ensure that all data users have access to sufficient information on the beneficial ownership of trusts without undue restrictions. Government users, financial institutions, and DNFBPs should have direct access. Providing public access to the beneficial ownership information of trusts is likely an effective tool to prevent the misuse of trusts. However, there are various legitimate privacy concerns surrounding trusts, such as the interests of minors, which may warrant limiting public access to information. To achieve a balance between privacy and the benefits of broader access to BO information, some countries (including, for example, the United Kingdom) only allow third parties that can demonstrate a legitimate interest access to BO information for trusts. Discussions on this type of access have focussed on how a narrow definition of legitimate interest and the potential bureaucracy around accessing information means it is unlikely to deliver the potential benefits that public access would. [89]

Discussion

South Africa’s privacy legislation provides strong protection of individual information. As discussed in the section on the legal landscape in South Africa, there are various pieces of legislation that protect the personal information of individuals. Currently, an interested party must apply in writing to the relevant Master’s Office for access to trust information, providing reasons why the information is needed. The Master will then consult with the trustees and beneficiaries before making a decision. Should the Master decline access to the information, the interested party can lodge a PAIA application to the Department of Justice’s Information Officer. [90]

Due to the capacity challenges at the Master’s Office and the lack of a clear definition of material or legitimate interest, this process effectively means that there is no public access to BO information for trusts in South Africa. There is also no provision that allows for making the BO of trusts that appear in ownership structures of legal entities publicly available.

A major challenge identified by investigative authorities is the lack of bulk access to trust information, preventing authorities from conducting proactive investigations. Upon conducting an investigation into the beneficial ownership of trusts, investigators will have to prove a material interest in a specific, identified trust in the same way the public must prove such interest, which slows down investigations and creates a bureaucratic burden on both the investigative authority and the Master’s Office. Additionally, since trustees are also notified of any information request, any parties using trusts for illegitimate activities will be notified that they are being investigated.

In developing an effective access regime, policymakers may consider:

- Providing exceptions to the publication of information for specific types of trusts, informed by risk-based assessments. However, to avoid the risk of creating a loophole, these types of trusts must still comply with all other disclosure requirements and should not receive exemptions in making disclosures to the Master’s Office.

- How best to provide rapid and efficient access to competent authorities like SARS, the National Prosecuting Authority (NPA), and the FIC. Should this be granted, clear levels of access should be identified to ensure that only competent and authorised investigators have access to sensitive information. Policymakers should also consider whether to grant general access to confidential trust documents (such as letters of wishes) to competent authorities.

- When it comes to the beneficial ownership of legal entities, the CIPC provides higher level access to law enforcement agencies (through an MOU with the South African Police Service) and has a unit dedicated to assisting law enforcement agencies with requests for information during investigations. This approach could be duplicated by the Master’s Office.

- Whether to remove the legitimate interest requirement to information access of trusts where there is a public interest implication, e.g. where trusts appear in the ownership chain of companies involved in public sector procurement.

- How to manage access to information for investigative journalists, whether journalists have to prove a legitimate interest, and if so what the threshold for legitimate interest is.

- The implication of POPIA and its definition of public interest.

- Sanctions for abusing access to information by authorised individuals or organisations.

Stakeholders interviewed in the preparation of this briefing acknowledged the importance of safeguarding the personal information of parties involved in a trust and that there are a wide range of legitimate reasons to keep some information private. However, the relationship between South Africa’s various privacy laws and its impact on making BO information publicly available is complex and creates uncertainty. Identifying specific exemptions and levels of data access will contribute to providing clarity on the limitations of privacy protections.

Ultimately, policymakers will have to determine the right balance between protecting the legitimate privacy interests of parties involved in trusts and the public interest of the BOT of trusts. There should also be well-defined rules setting out any exceptions to privacy protections or disclosure requirements.

Key considerations

- Determine the feasibility of adopting memorandums of understanding (MOUs) or service-level agreements between competent authorities and the Master’s Office for unfiltered access to trust information in a variety of ways, including per-record search and bulk access, and the conditions attached to access. Any such agreements must identify the specific authorities that are regulated by the agreement.

- Ensure efficient access for financial institutions and DNFBPs.

- Review and adopt a formal definition of legitimate interest for broader access to trust information. During this review, the various factors that may impact access to BO information, such as privacy, public interest, and protection of the interests of minors and mentally incapacitated beneficiaries, should be considered.

- Consider adopting specific access measures for investigative journalists.

- Determine and adopt sanctions for abusing access to information.

Structured data

The collection, storage, and sharing of structured data that is interoperable is the best way to ensure information on the beneficial ownership of trusts can be easily used for its intended purpose. [91] Structured data is data that:

- is captured using a standardised format;

- has a well-defined structure;

- is organised according to a data model;

- follows a persistent order;

- is available in machine-readable formats; and

- is usually stored in a database. [92]

High-quality, structured data can be used and cross-referenced more easily and cheaply with data analysis tools. This may require training investigators. However, investments made into the production of structured data and the use of data standards are likely to generate more valuable insights into the activities and operations of trusts and their beneficial owners. [93] It remains critical that the data produced is interoperable so that it can be combined with information from other registers, different jurisdictions, or non-BO datasets to effectively identify beneficial owners.

A key aspect of structured data is the use of unique identifiers to identify individuals, trusts, and companies across different datasets. [94] Without such unique identifiers, management of datasets will be labour intensive and simple human errors, like misspelling names, may result in missed connections. Furthermore, structured data allows for data analysis across different databases. [95]

Should South Africa successfully implement a structured data standard (potentially BODS, discussed below), the BO information of legal entities can easily be linked to the BO information of legal arrangements. As South Africa is considering BO reforms for legal entities and trusts at the same time, structured data use provides a unique opportunity to maximise the impact of such reforms.

BODS is an open standard for publishing high-quality, machine-readable data on beneficial ownership and is based on the needs of both data publishers and data users. It is designed to be used by authorities managing a register or registers of ownership and is intended to capture, manage, and share data in a way that provides useful insights into beneficial ownership of legal entities and arrangements (which includes trusts). [96]

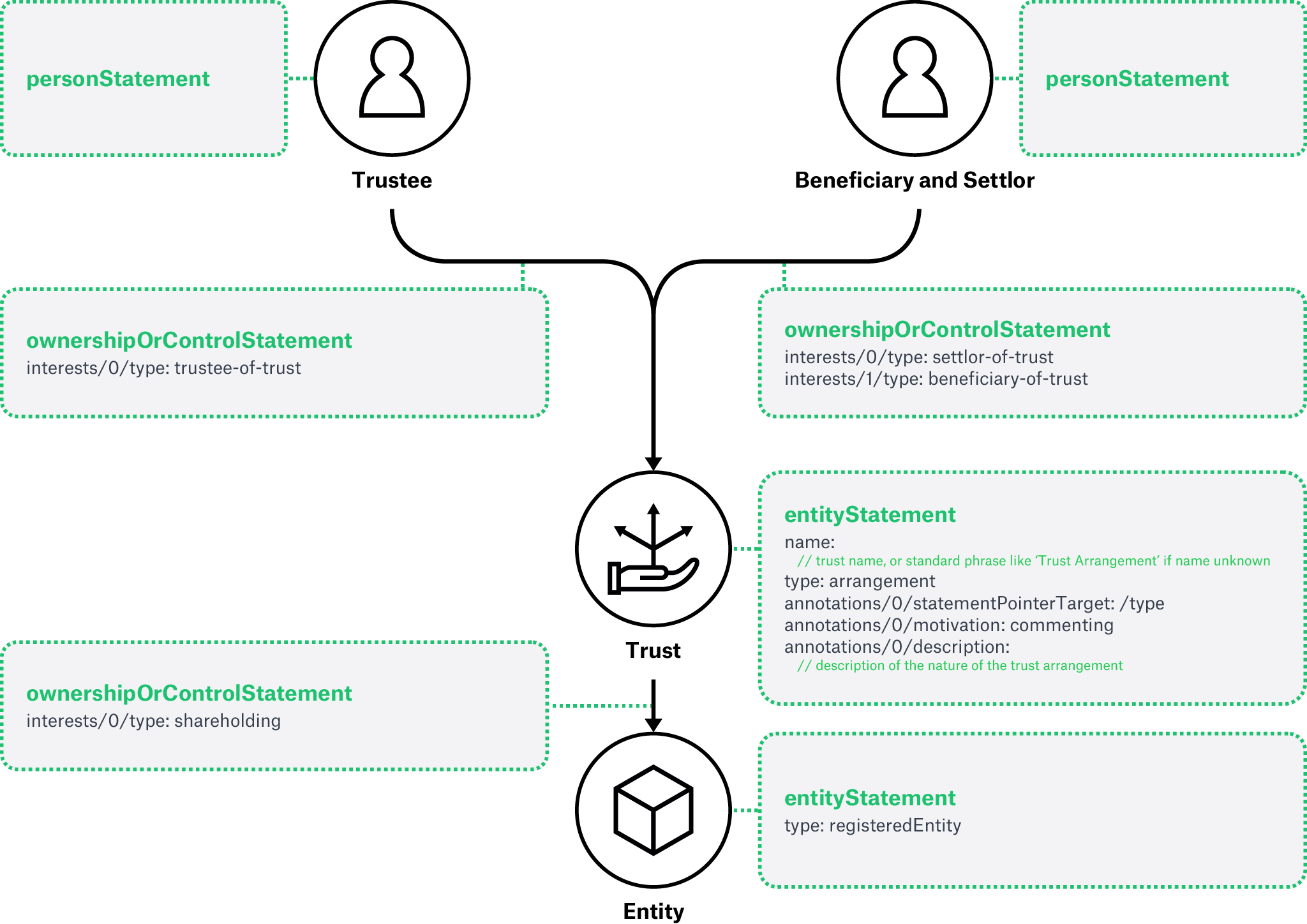

At its most basic level, BODS is intended to identify the links between individuals, legal entities, and arrangements by capturing and connecting chains of ownership or control. Ideally, the data standard will be used in all registries in South Africa, which will allow for tracking and linking ownership chains across registries. BODS uses three types of statements:

- The person statement captures the personal information of individuals, including names, personal identification numbers, date of birth, etc.

- The entity statement captures the information of the entity in question, such as the name of the trust, the trust registration number, the unique identifier, or the type of trust.

- The ownership or control statement defines the relationship between the individual (identified in the person statement) and the entity (identified in the entity statement). In the case of trusts, this may include the settlors, trustees, beneficiaries, or protectors.

Box 4. Representing trusts in BODS v0.2

Discussion

As things stand, the relevant authorities and regulators are not collecting structured data in relation to BO information. [97] Stakeholders believe the work being done at the level of the IDC on BOT is likely a step in the right direction to ensure the collection of structured data across all relevant databases, which will ultimately unlock the potential benefits by enabling data use. However, such efforts will require clarity on the mandate of each regulator to ensure effective cooperation between the different entities.

A critical step towards structured data is full digitalisation of the Master’s Office’s trust records. The experience of the CIPC provides a useful example of the benefits of digitalisation and automation. The CIPC allows its customers (legal entities) to self-capture all relevant ownership information online, which reduces the risk of error and eliminates the use of paper-based systems. Whilst the CIPC does not currently use a data standard such as BODS, there is currently a process underway to shift towards the use of structured data.

The Master’s Office, as the current custodian of trust information, still relies largely on paper-based systems. Whilst a digitisation process is underway, progress is slow due to institutional limitations and the fact that, for trusts registered from 2012, only the name, registration number, and trustees’ names are currently accessible digitally. To the authors’ knowledge at the time of writing, the technological requirements of establishing an effective BOT regime in South Africa has not yet been scoped.

Whilst adopting structured data standards should be an ultimate goal, the reality is that such adoption will take time and require careful collaboration between various stakeholders. One of the most complex aspects of adopting structured data is that the different entities (trusts, legal entities, and non-profit organisations) have different structures of ownership and decision-making, which leads to challenges with data collection and standardisation. The use of APIs can facilitate sharing structured data with various data users. [98]

Key considerations

- Consider publishing BO data for both legal entities and arrangements to the BODS, and develop an implementation roadmap for structuring existing data.

- Determine how to make data interoperable with information about the beneficial ownership of legal entities, for instance, through the use of unique identifiers.

- Consider the use of APIs as a potential option for data sharing between competent authorities, financial institutions, and DNFBPs.

Verification

The effective use of BO information requires that data users can trust that the data captured in the register is a reasonably accurate and up-to-date reflection of who exercises control over a trust. This is achieved through verification, a combination of checks and processes to ensure that BO data is accurate and complete at a given point in time. [99]

When a trust is registered, measures should be taken to verify the data. This includes verifying the trust’s documents, such as the trust deed, letter of wishes, and power of attorney upon registration.

Discussion

When registering a trust with the Master’s Office, the settlor (or anyone acting on their behalf) must provide certified copies of the relevant identity documents; proof of registration of any legal entities; the original trust deed (or a copy certified by a notary); original signed forms; sworn affidavits by any independent trustees; and final certified court order, where applicable. The mechanisms for verifying information at the time of registration thus seem to be sufficient, although proactive analysis of bulk data on trusts to raise red flags of potential misuse by, for example, the FIC, could complement these verification mechanisms. [100]

Whilst legal obligations to collect BO information are already in place for financial institutions and DNFBPs, greater clarity is required with regards to the extent of those obligations. The veracity of beneficial ownership of trusts information is a challenge due to the lack of updated and verified information, and reforms should consider the obligations of all stakeholders, including competent authorities and reporting entities/financial entities, when it comes to collecting and disclosing beneficial ownership of trusts information.

Key considerations

- Create legal obligations to submit relevant supporting documents (such as the trust deed, letter of wishes, verified forms of identity documents, etc.) when BO information is submitted, and for the registrar to implement mechanisms to ensure the accuracy of information in the register.

Up-to-date and historical records

Each country should establish methods to ensure that BO data is kept up to date and historical records are maintained to enable auditing. Whilst trusts are likely to have fewer and less frequent changes to BO information compared to legal persons, it is still critical that any changes in BO information are submitted in a timely manner. Additionally, BO information should be periodically confirmed as correct, and an auditable record of the beneficial ownership of trusts should be created and kept. This includes maintaining historical records about changes to trusts, terminated trusts, and inactive trusts. [101]

Discussion

The challenge with verification lies with updating information and verifying whether the information the Master’s Office has on record is up to date. Any changes to a trust deed (which includes the identity of beneficiaries or classes of beneficiaries) or change in trustees should be registered with the Master’s Office (following prescribed procedures, including submitting certified documents), but such changes are subject to self-reporting from the trustees. [102]

The challenge of ensuring information is updated is less pronounced with trusts established after 2012 (as such information has been digitised), but the paper-based nature of recordkeeping of older trusts means the information on those trusts is often not up to date. One potential way to address this gap is to require trustees to submit an annual declaration that all the information registered with the Master’s Office remains accurate.

Key considerations

- Develop an action plan to ensure that all the information held by the Master’s Office is verified and updated within set timeframes, and historical records are kept.

- Consider whether any additional actions and stricter enforcement mechanisms are required to improve self-reporting of any changes to BO information.

- Consider transaction thresholds for trusts and the reporting requirements linked to transactions above such thresholds.

Sanctions and enforcement

Governments should ensure that effective, proportionate, dissuasive, and enforceable sanctions for noncompliance are in place to hold parties that do not comply with disclosure requirements accountable. Such sanctions should be in place for all types of noncompliance, including non-submission, late submission, incomplete submission, or false submission. Sanctions should be applicable on the person making the declaration, the beneficial owner(s), the trustees, and the trust (in the form of its assets). [103]

Sanctions may include monetary penalties; prevention from opening bank accounts; acquiring property or assets; freezing accounts; or prevention from entering into business relationships or conducting transactions. [104] Additionally, sanctions can be enforced against individuals providing professional services (such as auditors or lawyers) to trusts or trustees. These sanctions may include revoking professional licences or disbarring or banning such individuals from holding positions with fiduciary duties. Finally, criminal sanctions may also be enforced against individuals when violating disclosure requirements with criminal knowledge and intent. [105] Implementing agencies can also consider giving legal effect to registration to improve compliance. For example, by requiring a trust to be registered to be legally valid, or for beneficiaries to be required to be registered before being legally able to benefit from the trust.

Discussion

Currently, the only sanctions that are directly applicable to disclosure requirements of trusts are found in the TPCA. According to section 20 of the Act, the Master of the High Court may remove a trustee should they fail to fulfil their duties in accordance with the Act. Additional sanctions for non-disclosure or false disclosure are imposed by the FICA, which could lead to penalties in the forms of fines, not exceeding ZAR 15 million fine, or up to 15 years imprisonment. However, these sanctions are largely applicable to accountable institutions, and it is not clear whether the beneficial owners of a trust could be held liable under these sanctions.

Whilst political support for BOT reform is high, critics argue that significant resource allocation is required for political will to be translated into action. In fact, whilst the NPA’s total budget increased in the 2021/2022 financial year, the real value of that increase was negligible after factoring for inflation. The NPA recently indicated that it would require an additional minimum of ZAR 1.7 billion per annum to modernise the institution and to prosecute cases identified during the State Capture Commission. [106] Without sufficient financial resources for prosecuting authorities, especially with regards to investigating complex legal structures, there is little hope of enforcing effective sanctions on those abusing trusts to conceal their involvement in illegitimate transactions.

Whilst there are sanctions in place, South Africa’s BOT of trusts regime would be best served with specific sanctions designed for non-disclosure of BO information. Clearly defining the parties that could be held liable for noncompliance with disclosure requirements, and the penalties applicable to such noncompliance, will create the level of clarity required for effective, proportionate, dissuasive, and enforceable sanctions.

Key considerations

- Establish sanctions in law for individuals and firms that fail to meet reporting obligations. Clearly define the competent authority responsible for enforcement of these sanctions and which parties can be held liable for not complying with reporting obligations.

Challenges to implementing the beneficial ownership transparency of trusts [107]

The research conducted in preparation of this briefing has identified a number of constraints that should be addressed to reform the BOT of trusts in South Africa:

- Legislative gaps: Whilst a comprehensive suite of legislation exists which authorities can use to implement BOT of trusts reforms, there remain gaps that create uncertainty. [108]

- Trust legislation: Experts in the trust creation and administration industry have noted that the lack of legal personality provided to trusts creates uncertainty, especially since trusts are often treated as having legal personality in practice. Amending trust legislation to accommodate trusts as juristic persons will address the lack of certainty and consistency.

- Institutional capacity: South Africa’s law enforcement agencies, judicial entities, and regulators are under-staffed and under-resourced. Various stakeholders also indicated that institutional capacity, which includes “hands on deck”, remains a challenge in all efforts to implement an effective BOT regime.

- Skills and knowledge gaps: The complexity of trusts and other complicated legal arrangements poses a challenge to investigators, who often do not have the training to understand such complex legal arrangements. In contrast, bad actors use highly skilled legal practitioners and advisors to set up these complex structures.

Understanding and overcoming these identified challenges, which is not an exhaustive list, is critical for moving towards an effective BOT of trusts regime. As the privacy protections of trusts are more complex than those applicable to other legal entities, steps taken to improve the BOT of trusts will likely have a positive effect on BOT measures in general.

Endnotes

[74] Olivier et al., Trust Law and Practice.

[75] For example, trusts are treated like legal persons in contractual relations, various aspects of taxation, and in estate planning, despite the theoretical assertion that trusts are not legal persons. See: Olivier et al., Trust Law and Practice.

[76] Olivier et al., Trust Law and Practice.

[77] Chhina, Beneficial ownership transparency of trusts.

[78] Connection to South Africa might mean that beneficiaries, trustees, or founders are South African citizens/registered for South African tax, or that assets are held in South Africa. See: Chhina, Beneficial ownership transparency of trusts.

[79] Chhina, Beneficial ownership transparency of trusts.

[80] Olivier et al., Trust Law and Practice.

[81] For details on the information that should be collected on the trust, the beneficial owners, and any companies/legal entities in the ownership chain, please see: Chhina, Beneficial ownership transparency of trusts.

[82] See Form J401: “Trust Registration and Amendments Form (Inter-Vivos)”, Republic of South Africa, n.d., https://www.justice.gov.za/master/m_forms/J401_trust-registration-amendment-eform.pdf.

[83] Olivier et al., Trust Law and Practice.

[84] Form J401.

[85] Olivier et al., Trust Law and Practice. Also see Form J405: “Undertaking by Auditor/Accountant (Inter-Vivos Trust)”, Republic of South Africa, n.d., https://www.justice.gov.za/master/m_forms/J405_acceptance-auditor-eform.pdf.

[86] Maíra Martini, Who is behind the wheel? Fixing the global standards on company ownership (Berlin: Transparency International, 2019), https://images.transparencycdn.org/images/2019_Who_is_behind_the_wheel_EN.pdf.

[87] Chhina, Beneficial ownership transparency of trusts.

[88] “ICMS Master’s Office Web Portal”, the Master of the High Court, the Department of Justice and Constitutional Development, Republic of South Africa, n.d., https://icmsweb.justice.gov.za/mastersinformation/Account/Login?ReturnUrl=%2fmastersinformation.

[89] HM Revenue & Customs, “Ask HMRC for information about a trust”, Gov.uk, 1 September 2022, https://www.gov.uk/guidance/ask-hmrc-for-information-about-a-trust; Graham Barrow and Ray Blake, hosts, “Trivia - when three paths meet” The Dark Money Files (podcast), 3 December 2022, https://www.buzzsprout.com/242645/11805918-trivia-when-three-paths-meet; Tymon Kiepe, “Making central beneficial ownership registers public”, Open Ownership, May 2021, https://www.openownership.org/en/publications/making-central-beneficial-ownership-registers-public.

[90] “Administration of Trusts”, the Master of the High Court.

[91] Tymon Kiepe and Jack Lord, “Structured and interoperable beneficial ownership data”.

[92] Tymon Kiepe and Jack Lord, “Structured and interoperable beneficial ownership data”; “What is Structured Data?”, TIBCO, n.d., https://www.tibco.com/reference-center/what-is-structured-data.

[93] Chhina, Beneficial ownership transparency of trusts.

[94] Chhina, Beneficial ownership transparency of trusts.

[95] Chhina, Beneficial ownership transparency of trusts.

[96] For more information on BODS, and for examples of how it can be used in the BOT of trusts, see: “What is the Beneficial Ownership Data Standard?”, Open Ownership, n.d., https://standard.openownership.org/en/0.3.0/primer/whatisthebods.html.

[97] Relevant regulators include the CIPC, the Master’s Office, SARS, and the Department of Social Development. The CIPC is currently undergoing a process of establishing data standards.

[98] APIs are mechanisms that enable two software components to communicate with each other using a set of definitions and protocols. In other words, one regulator may access the data held by another and use it within its own system using an API. See: “What is an API?”, Amazon Web Services, n.d., https://aws.amazon.com/what-is/api/.

[99] Chhina, Beneficial ownership transparency of trusts.

[100] “Administration of Trusts”, the Master of the High Court.

[101] Chhina, Beneficial ownership transparency of trusts.

[102] Olivier et al., Trust Law and Practice.

[103] Chhina, Beneficial ownership transparency of trusts.

[104] Chhina, Beneficial ownership transparency of trusts.

[105] Ramandeep Kaur Chhina and Tymon Kiepe, Designing sanctions and their enforcement for beneficial ownership disclosure, Open Ownership, 28 April 2022, https://www.openownership.org/en/publications/designing-sanctions-and-their-enforcement-for-beneficial-ownership-disclosure/.

[106] Jan Gerber, “NPA needs a further R1.7bn to lock up state capturers and to modernise the organisation”, News24, 11 May 2022, https://www.news24.com/news24/SouthAfrica/News/npa-needs-a-further-r17bn-to-lock-up-state-capturers-and-to-modernise-the-organisation-20220511.

[107] The challenges discussed in this section are based on insights gathered through expert stakeholder interviews.

[108] On 29 August 2022, the Minister of Finance introduced the General Laws (Anti-Money Laundering and Combating Terrorism Financing) Amendment Bill to South Africa’s National Parliament. Following public comment and parliamentary approval, the Bill was signed into law in December 2022. Whether the Bill will cover all legislative gaps has not been considered for this briefing. However, many implementation details will be covered by secondary legislation which this briefing can still inform.