Catalysing transformative change in beneficial ownership transparency

Programme design implications

Criteria for country selection

From the research, OO and EITI maintain that the programme should initially prioritise countries where initial interventions are likely to lead to concrete advancements in reform and increase in data use, i.e. countries that have the highest chance of successful BOT implementation and impactful use of BO data. How this can be understood necessitates considering a number of factors that will need to be assessed through both qualitative and quantitative measures.

The research confirmed that rule of law, regulatory effectiveness, and political will are key factors in successful implementation. They are also key enablers for impact, and therefore should be considered in country selection.

Political will has been identified through the research as the most important factor, but also one of the most difficult to assess, largely because it comprises many things. Accurately assessing political will requires understanding and assessing its separate components; the means to understanding these vary, including:

- What political commitments have been made and what are they aiming for? (E.g. committed to a register but not public; committed to a register for the extractives sector only.)

- Are there BOT champions and coalitions that can be identified?

- What are the incentives for reform at the political level? At the implementation level?

- How is inter-stakeholder coordination and collaboration?

- To what extent are politicians perceived to be involved in extractives-related corruption?

- Can we identify a clear lead agency? Can we identify government implementers who are likely to be there in the longer term, as well as implementers with good access and opportunities for inter-governmental coordination?

FATF Mutual Evaluations are a powerful driver, and the evaluation schedule can be factored into country selection as well as new BOT commitments under the IMF COVID-19 relief fund, as these may provide new entry points or strengthen existing commitments. As the FATF requirements are less ambitious than what we are trying to achieve with this programme, the programme should prioritise countries where there are also strong anti-corruption incentives for reforms, including at minimum an EITI commitment to BOT.

Political stability should also be factored into political will to assess whether political will is sustainable over time.

It will be important to identify incentives to implement BOT reforms and commitment at the implementer level, not just the decision-maker level. If the country has already passed BOT legislation, it will be important to conduct an extensive legal review, as loopholed and flawed laws can severely undermine implementation.

Whilst the programme can have an influence on certain criteria related to impact (e.g. sensitisation, capacity to use data), the programme should prioritise countries where there is an active civil society as well as a responsive judicial system, and for there to be civic freedoms including a relative freedom of speech and media. Criteria where the programme can have little influence should not be prioritised in the initial selection.

A key insight is that data use is key to impact, and data use depends on sensitisation and understanding. Therefore, the programme will need to factor this into its service offering (see following section). To this end, the programme will need to focus on countries with corruption in the extractive industry in order to have some early impact and build legitimacy. As this can also undermine political will and implementation, it would seem risky to focus explicitly on countries with high levels of corruption.

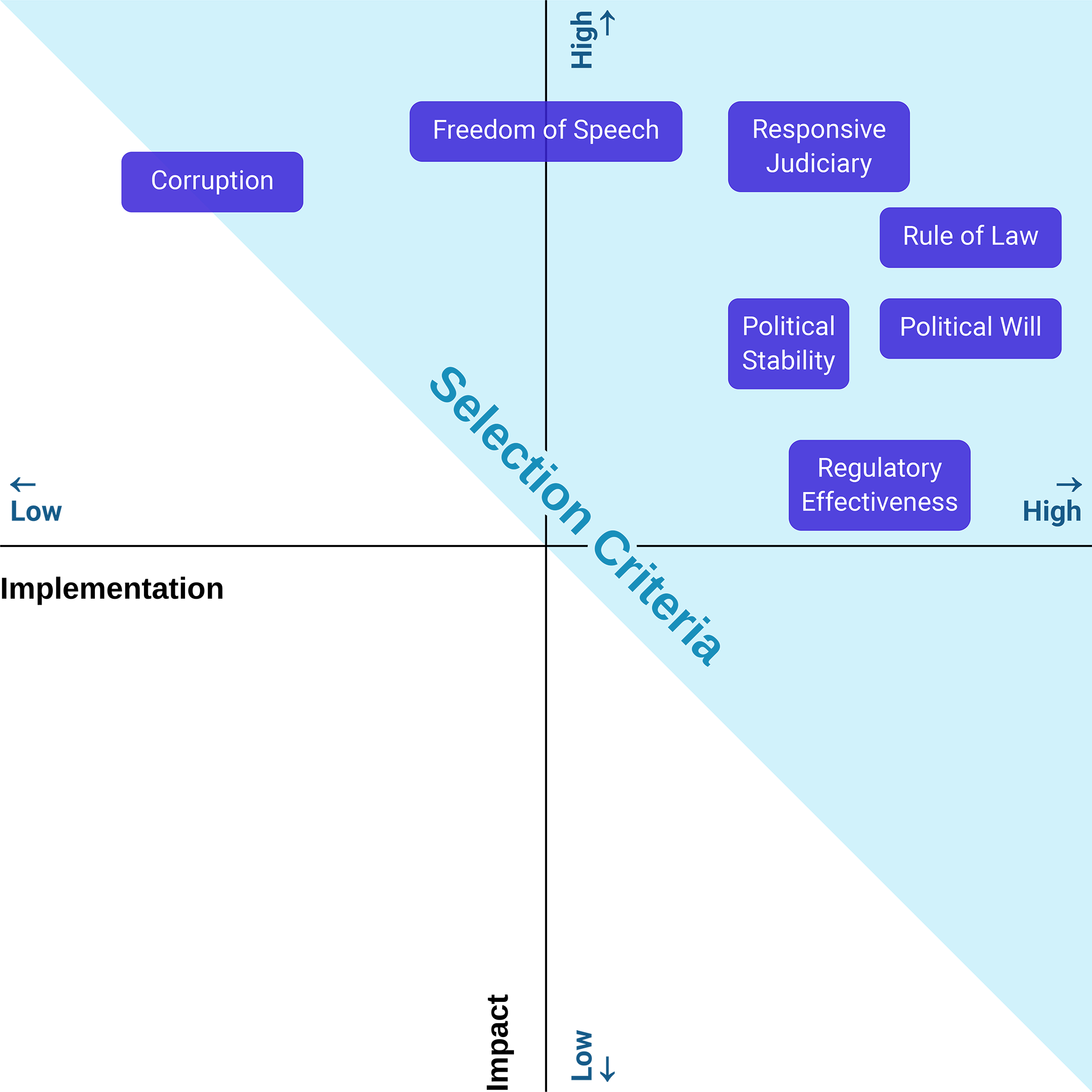

Figure 2. Mapping of criteria against their perceived effect on implementation and impact

The research has informed changes to how we categorise our criteria. Whilst it remains important for the program to consider which criteria affect implementation success and impact, we found that categorisation of the criteria did not cohesively fit how the categories would be used. We found that the factors or criteria affecting implementation and impact overlapped. For instance, the rule of law relates to the responsiveness of the judicial system, and there is a role of impact in sustaining political will. Therefore, implementation and impact cannot be fully separated.

Furthermore, the degree to which the factors were necessary prerequisites for engagement, versus the degree to which we could be able to influence the factors – therefore determining level of support – varied. The existence of a government commitment, for example, is an important prerequisite, but existence of BOT champions would require more direct access to, and communication with, the implementing government. We are also able to influence different aspects of political will. Such criteria should not only inform the country selection but also the subsequent offering of services.

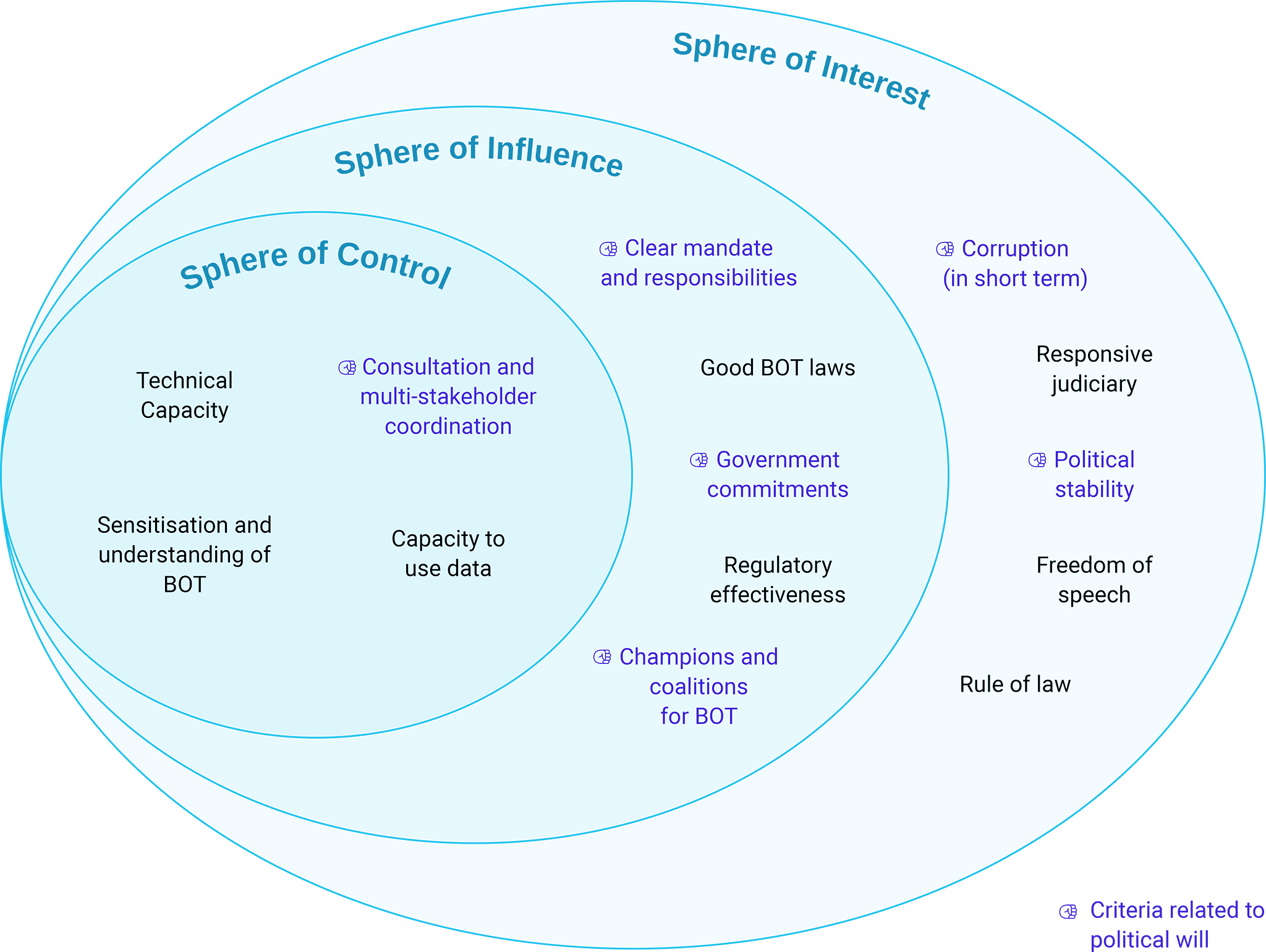

Instead, the criteria should be seen in terms of the influence the programme can have over them. This ranges from criteria that the programme will be able to directly affect through the support offered in a country (sphere of control); the criteria the programme may affect (sphere of influence); and the criteria that the programme cannot affect but which will affect implementation (sphere of interest).

Figure 3. The spheres of control, influence, and interest of the proposed programme

Defining a portfolio

In order to mitigate some of the risks associated with these criteria, the programme can consider a funnel approach to country selection. This entails initially starting with smaller activities in a larger number of countries, from which the most promising countries can be selected to work with in greater depth as the programme progresses. Targeted interventions to support specific implementation needs can then be designed based on initial scoping research, mapped against the criteria and programme outcomes.

For example, a number of research respondents pointed towards the necessity of impact stories from different stages of the implementation journey. With limited capacity, this would require balancing the country portfolio, and prioritising country selection based on the potential for the largest measurable impact as a result of the programme on the one hand, and desire for impact stories in various regions and at different stages of implementation on the other hand.

Based on EITI and OO’s knowledge from national level interventions to date and findings from the design research, the following selection criteria are proposed to assess the likelihood of succesful BO implementation and the level of subsequent impact in the new framework:

|

Criteria within sphere of control |

Criteria within sphere of influence |

Criteria within sphere of interest |

|---|---|---|

|

1.1 Technical capacity Assumptions: Higher levels of technical capacity lead to more successful implementation. |

2.1 Government commitment and incentives Assumptions: Commitment from the top level of government is important for political will to sustain implementation. |

3.1 Level of corruption involving the extractives sector Assumptions: Higher levels of corruption in the extractives sector translate into larger impact when BOT is implemented. |

|

1.2 Sensitisation and understanding of BOT Assumptions: An understanding of BOT from all involved stakeholders supports effective implementation and impact. |

2.2 Governance and regulatory effectiveness[14] Assumptions: Higher governance/regulatory effectiveness leads to more effective implementation of policy/legislation. If further along in implementation, the quality of laws is important for implementation. |

3.2 Rule of law and responsive judiciary Assumptions: Adherence to legislation is important for successful implementation and achieving impact. |

|

1.3 Progress along BOT journey Assumptions: Meaningful progress towards BOT at the point of engagement increases the chance of successful/effective implementation. |

2.3 Clear mandates and responsibilities Assumptions: A clear mandate for the lead agency, and clear responsibilities of all implementing actors, facilitates implementation. |

3.3. Political stability Assumptions: Political stability is key to sustaining political will over time. |

|

1.4 Multi-stakeholder coordination and consultation Assumptions: Effectively coordinating and consulting between different stakeholders (government actors, civil society, and industry) is important for successful BOT implementation and enabling data usability for impact. |

2.4 Demand for BOT from existing user groups Assumptions: The existence of users who want and are able to use BO data to drive impact is a key enabler for impact. |

3.4 Civil liberties Assumptions: Freedom of speech and the media and existing civic space are required for meaningful stakeholder participation in implementation and for civil society to be a meaningful data user/oversight actor for impact. |

Implications for programme activities

A clear finding from the research is that the implementation of BOT in different contexts will require bespoke combinations of support. From EITI and OO’s experience, as well as the research, it does not seem practical to identify a typology of implementing countries, and subsequently design specific implementation models to match these. Defining specific service portfolios for countries based on general factors such as income group and geography does not seem useful. The programme may be best delivered by ensuring that OO and EITI have their combined service offering as a menu of support services, addressing challenges based on specific needs at different stages of implementation. For example, this could include helping think through what a verification system could look like and the resources required at early stages of implementation, or a legal review to ensure there is a legal basis for data exchange between different government actors when implementing a verification system. That being said, it is clear that addressing issues around data publishing – data quality and usability, as well as accessibility and interoperability – need to be woven in throughout whatever support is given and should be a focus from the outset. Designing the programme as a menu of support services means that the programme’s monitoring, evaluation, and learning framework becomes incredibly important to constantly assess whether targeted interventions are supporting specific implementation needs.

Implications for specific support services

Besides the intrinsic importance of impact, it also appears to be critical to sustain implementation by creating legitimacy. Data users are key to driving impact, and there are no data users without sensitisation and understanding. As sensitisation seems to be one of the most important demands, it will need to be included in the support services for all potential data users. The research shows that there is a large demand to help people understand BOT in simple and accessible terms. Sensitisation will mean different things for different actors. The programme will need to develop a number of use cases and tailor these to different stakeholder groups. This should also address context specific concerns (e.g. capital flight) that emerge during initial assessments. Sensitisation could include building capacity to use the data. For instance, helping extractive industry regulators and licensing agencies in accessing and using BO data.

There is a strong demand for assistance in developing legislation and the drafting of laws. However, it also seems that there is a lot more support available for this. The programme should therefore be able to advise on main policy principles to adhere to when developing legislation, and how certain decisions at the legislation stage impact implementation further on.

Almost all respondents mentioned verification and improving data quality as a key challenge. The programme should consider developing easily deployable verification systems suited to different contexts (e.g. high- and low-tech). Standards of data collection need to be established and maintained to allow for future interoperability of data as countries expand their BO regimes beyond the extractives sector (as we have seen in Armenia and will see in Nigeria).

The research suggests that COVID-19 has highlighted the importance of digital access to data and has led to government agencies introducing virtual collaborative approaches to working. This presents opportunities for the programme, including peer learning across countries.

Implications for programme beneficiaries

BOT reforms have primary benefits within and across government. However, due to the demand for sensitisation of all data users and their role in achieving impact and sustaining political will, the programme should consider treating civil society and industry as primary beneficiaries from the outset of the design, who have proven to be potential drivers and catalysts for reform. The programme could differentiate between primary beneficiaries who are drivers, catalysers, or intermediaries versus lead implementers, as this would affect who would be benefitting from the main support services provided. EITI MSGs should be seen as intermediaries, coordinators, and facilitators, rather than implementers, although EITI National Secretariats may be implementers in some contexts.

Industry is not monolithic, and therefore understanding how BOT information is used differently by different companies (for example, of different sizes) within and across sectors is an important consideration for this project. Understanding how companies in the extractives sector will use the data, as well as what other businesses they interact with, will inform how to make the case for BOT. The research has indicated that there is at the very least a perception from implementers and international experts that many in the extractive industry – including regulators – may not currently be actively using BO data where it is available, which will require specific focus in the programme.

The programme should differentiate between different CSO actors, and consider their role not only as data users but also as advocacy and oversight actors that can ensure that BOT reform is undertaken in the right way, and should also consider engaging civil society stakeholders outside the anti-corruption movement.

The programme should consider whether to reflect other government agencies such as statistics offices and local authorities in potential government data users, and consider planning outreach and stakeholder engagement targeting government agencies as users.

COVID-19 programme implications

The effect of COVID-19 at the national level should be considered in the selection of countries. Specific criteria related to COVID-19 are not advisable, as the effect varies per country. For example, COVID-19 may have increased or decreased public demand for BO data. Scandals related to public procurement may increase demand, especially when coinciding with the economic crisis related to COVID-19. A country with strong political will to implement BOT may be unwavering in their commitment, but may need more support than before due to COVID-19 constraining government resources. For countries with limited political will, the crisis may serve as a pretext to delay BOT implementation. The direct and indirect effects of COVID-19 may not fully show in the indicators used for country selection, if those rely on data from previous years. Therefore, the implications of COVID-19 in each case should be considered additionally before concluding on focus countries and a “COVID-19 lens” should be applied to country selection criteria. For instance, the programme should assess to what extent a delay in implementation could be due to COVID-19 or other blockers, and should assess how COVID-19 has affected capacity.

Footnotes

[14] Quality of BOT laws, if present.