Charting New Waters: Strengthening Fisheries Governance through Beneficial Ownership Transparency

Challenges for Beneficial Ownership Transparency in Fisheries

Effective oversight and governance of fisheries tenure [5] is challenging because of the patchwork of international, regional and national rules and regulations, which overlap in some areas while leaving significant gaps in others. There are no international obligations on whether and how governments should collect and share information on parties that have an interest in fisheries tenure, although there are non-binding and voluntary guidelines. [6] Under the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, states have the right to exploit, in a sustainable manner, the marine resources within their exclusive economic zones (EEZs) – the area spanning approximately 200 nautical miles beyond their shores. [7] Regional Fisheries Management Organizations (RFMOs) provide a platform for deciding, coordinating and enforcing fisheries management measures in a given area, including setting limits on catch quantities and vessel numbers. The management of the majority of marine fish stocks falls within the remit of an RFMO, but some areas, such as the South Atlantic Ocean, are not covered. [8] There is significant divergence in tenure systems between countries, but often governments set a total limit for fishing particular species within a season. Rights to fish quotas within this limit are divided between different parties. While robust systems for quota allocation should include checks and balances to ensure the system of allocating rights contributes towards meeting fisheries policy goals, in many contexts the criteria upon which quota allocation decisions are made are not transparent. [9]

Transparency and Fishing Quotas

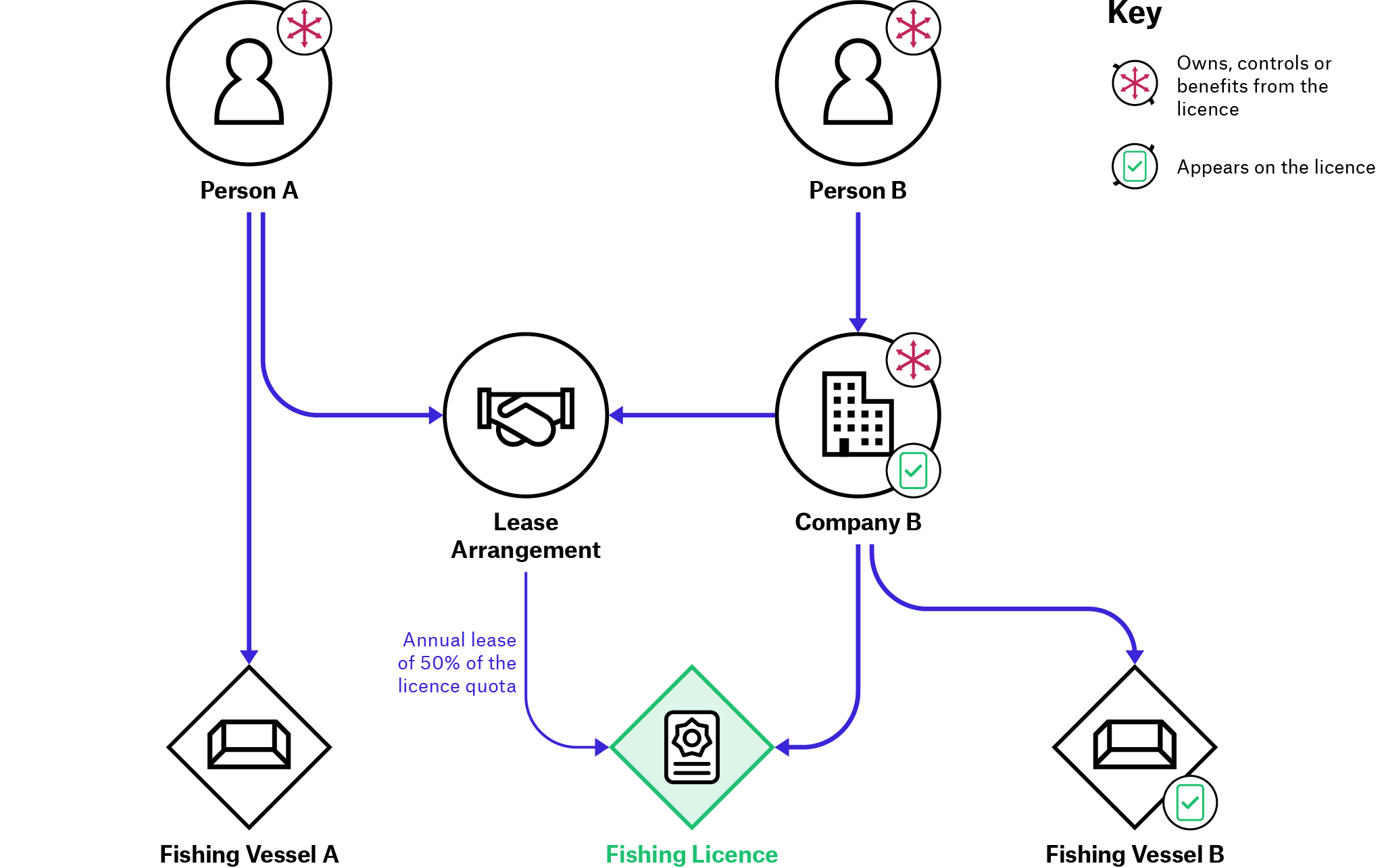

Many countries allow quotas to be freely sold and leased, which creates a substantial challenge to oversight as well as to establishing who ultimately owns, controls and benefits from fishing rights. [10] It is often possible for multiple parties to have an interest in the rights associated with licenses. Interests may be ultimately held by the legal owners’ beneficial owners. While the legal owner is usually registered, additional parties may also hold interests, particularly where certain rights are separated through arrangements or agreements (see Figure 1). This would be the case, for example, where one owner holds the fishing license while the quota is used by another party, or where a single vessel is registered as holding the lead quota but then leases parts of this quota to other vessels and operators. In some systems, the purchaser of a quota may not even be required to be licensed or to be a locally registered fishing operation, enabling agents and brokers to also play a significant role in fisheries tenure. [11]

Figure 1. Illustrative Example of Parties to a Lease Arrangement of a Fishing License

In this example, Company B and Fishing Vessel B are authorized to fish a specific quota through a fishing license. Person B owns and is the beneficial owner of Company B. Person A leases 50 per cent of the license, and fishes this quota using Fishing Vessel A. Despite other parties (i.e. Person A operating Fishing Vessel A) owning, controlling or benefitting from the license, only Company B and Fishing Vessel B appear on the license. Source: Open Ownership. [12]

Vessel Registration

The registration and BO of vessels involved in fishing activities further complicate efforts to ascertain which individuals hold relevant interests in fishing operations (see text box). In this context, governments, RFMOs and others involved in fisheries governance may find it difficult to enforce regulations, achieve fisheries policy aims or ensure accountability of operations. As has been well documented by a range of multilateral and civil society organizations (CSOs), it also provides a context in which individuals behind IUU fishing and illicit activities can remain anonymous and unaccountable. [13]

Vessel Registration and Licensing

As with fisheries licensing, there are hugely differing approaches to vessel registration and no binding international agreements about how and where ships should be registered. [14] A vessel can be registered in a location altogether different from where it holds a fishing license or where it primarily conducts fishing activities. [15] While ownership information disclosure is required in order to register with the International Maritime Organization (IMO) – a UN body responsible for shipping-related security, safety and environmental issues – there is no requirement to provide BO information, and no shared legal definition of BO of vessels.

A vessel on the high seas needs to be registered in a country and fly its flag, and is subsequently subject to that country’s laws. Some jurisdictions set very few conditions – for example, with respect to safety and labor regulations – and carry out few inspections and enforcement actions, providing a competitive advantage to registration. [16] One study found that most vessels involved in illegal fishing in its sample were registered in jurisdictions with no requirement to disclose the true owners of the vessel. [17] In another study, of all vessels involved in IUU fishing, 70 per cent were flagged in financial secrecy jurisdictions. [18] Research suggests that as regulations change, IUU fishing vessels reflag to jurisdictions with weaker governance. [19]

Footnotes

[5] Fisheries tenure systems refer to the rights and responsibilities with respect to who is allowed to use which resources, in what way, for how long and under what conditions; how these rights are allocated; and who is entitled to transfer rights (if any) to others, and how.

[6] For example, there are voluntary guidelines produced by the FAO (FAO, Voluntary Guidelines on the Responsible Governance of Tenure on Land, Fisheries and Forests in the context of National Food Security (Rome: FAO, 2022), First revision, https://www.fao.org/3/i2801e/i2801e.pdf). These were endorsed by the World Committee on Food Security in 2012.

[7] United Nations (UN), “United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea”, 1994, https://www.un.org/depts/los/convention_agreements/texts/unclos/unclos_e.pdf. In addition, there are a number of environmental and other international agreements which may be relevant to fisheries. These include, for example: the FAO Compliance Agreement; the Agreement on Port State Measures; the Convention for the Protection of the Marine Environment of the North-East Atlantic; the Convention on Biological Diversity; the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals; the Rio Declaration on Environment and Development; the Work in Fishing Convention 2007; the Convention on the Conservation of Migratory Species of Wild Animals; and World Trade Organization rules, for example on subsidies, as well as other voluntary measures and initiatives. See: UK Government, Fisheries Management and Support Common Framework: Provisional Framework Outline Agreement and Memorandum of Understanding (London: Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs, 2022), https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/62068f21d3bf7f4f0981a0c7/fisheries-management-provisional-common-framework.pdf.

[8] Chatham House (The Royal Institute of International Affairs), Recommended Best Practices for Regional Fisheries Management Organizations (London: Chatham House, 2007), 1, https://www.chathamhouse.org/sites/default/files/public/Research/Energy%2C%20Environment%20and%20Development/rfmo0807.pdf; Alfonso Daniels, Matti Kohonen, Nicolas Gutman and Mariama Thiam, Fishy networks: Uncovering the companies and individuals behind illegal fishing globally (Boston: Financial Transparency Coalition, 2022), 6, https://financialtransparency.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/FTC-fishy-Network-OCT-2022-Final.pdf.

[9] Fisheries Transparency Initiative (FiTI), Transparency of fisheries tenure: Incomplete, unreliable and misleading? (s.l.: FiTI, 2020), https://www.fiti.global/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/FiTI_tBrief02_Tenure_EN.pdf.

[10] FiTI, Transparency of fisheries tenure, 7; Anthony Cox, Quota Allocation in International Fisheries (Paris: Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), 2009), 8, https://www.ccsbt.org/system/files/resource/en/4e37735815a1e/SMEC_Info_01__New_Zealand_OECD_quota_allocation_report.pdf.

[11] Canada House of Commons, “West Coast Fisheries: Sharing Risks and Benefits”, Report of the Standing Committee on Fisheries and Oceans, 42nd Parliament, 1st Session, 2019, https://www.ourcommons.ca/Content/Committee/421/FOPO/Reports/RP10387715/foporp21/foporp21-e.pdf.

[12] Kiepe and Low, Using beneficial ownership in fisheries governance, 6.

[13] See, for example: UNODC, UNODC Approach to Crimes in the Fisheries Sector (Vienna: UNODC, n.d.), https://www.unodc.org/documents/Wildlife/UNODC_Approach_to_Crimes_in_the_Fisheries_Sector.pdf; UNODC, Transnational Organized Crime in the Fishing Industry – Focus on: Trafficking in Persons Smuggling of Migrants Illicit Drugs Trafficking (Vienna: UNODC, 2011), https://www.unodc.org/documents/human-trafficking/Issue_Paper_-_TOC_in_the_Fishing_Industry.pdf; UNODC, Fisheries Crime: transnational organized criminal activities in the context of the fisheries sector (Vienna: UNODC, n.d.), https://www.unodc.org/documents/about-unodc/Campaigns/Fisheries/focus_sheet_PRINT.pdf; UNODC, Stretching the Fishnet: Identifying crime in the fisheries value chain (Vienna: UNODC, 2022), https://www.unodc.org/res/environment-climate/resources_html/Stretching_the_Fishnet.pdf; UNODC, Rotten Fish: A guide on addressing corruption in the fisheries sector (Vienna: UNODC, 2019), https://www.unodc.org/documents/Rotten_Fish.pdf. Other organizations include: the FiTI, the World Wide Fund for Nature, Financial Transparency Coalition, Global Financial Integrity and the OECD.

[14] “Registration of ships and fraudulent registration matters”, International Maritime Organization, 2019, https://www.imo.org/en/OurWork/Legal/Pages/Registration-of-ships-and-fraudulent-registration-matters.aspx.

[15] OECD, Evading the Net: Tax Crime in the Fisheries Sector (Paris: OECD, 2013), 20, https://www.oecd.org/ctp/crime/evading-the-net-tax-crime-fisheries-sector.pdf.

[16] North Atlantic Fisheries Intelligence Group (NA-FIG), Chasing Red Herrings: Flags of Convenience, Secrecy and the Impact on Fisheries Crime Law Enforcement (Copenhagen: NA-FIG, 2018), 30, https://norden.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:1253427/FULLTEXT01.pdf.

[17] According to NA-FIG, “Of the 197 vessels used for illegal fishing activities with a known flag state, 162 (or 82.2%) have been registered in [open registers]. Conversely, only 35 (or 17.8%) of these vessels have never been registered in an [open register]. The four most often used flag states for vessels engaged in illegal fishing activities [all have open registers].” See: NA-FIG, Chasing Red Herrings, 31, 67.

[18] Victor Galaz, Beatrice Crona, Alice Dauriach, Jean-Baptiste Jouffray, Henrik Österblom and Jan Fichtner, “Tax havens and global environmental degradation”, Nature Ecology & Evolution 2 (2018): 1352-57, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41559-018-0497-3.

[19] Galaz et al., “Tax havens and global environmental degradation”.

Next page: Benefits of Using Beneficial Ownership Information in Fisheries Governance