Defining and capturing data on the ownership and control of state-owned enterprises

Establishing which control mechanisms to record

The importance of control

Unlike in the case of an ordinary business, for SOEs, the people whom the state represents have no direct relationship to the entity – neither in regard to the usual benefit of profit, nor in control over operations. However, SOEs deploy public funds. It is therefore taxpayer money that has been invested and is at risk, as well as, potentially, the state’s natural resources, reinforcing the need for transparency to enable accountability and oversight. [13]

In any declaration by an SOE, it is recommended to capture information about the state or state agency involved – this is in addition to the usual information required about natural persons, to be able to comprehensively understand their ownership and control. In this context, only declaring the state ownership of an SOE is insufficient, and more focus should be put on those in control and the benefits that may arise from their positions of stewardship.

Benefits are not limited to remuneration and also include operational activities, such as a preferred status or advantage within a particular market; the choice of trade and procurement partners; and the ability to conclude other contracts. Successfully stewarding an SOE may also bring a level of prestige to an individual, granting them further personal opportunities.

Exploring control mechanisms

The ways in which states exert ownership or control over SOEs can be complex and often fall outside established definitions of beneficial ownership, requiring specific regulations and guidance to give clarity on the types of interest that should be disclosed. [14] In the absence of the usual types of individuals who meet the criteria of beneficial ownership, it is not uncommon for legislation to specify others who have a degree of control over the business and/or details on persons holding particular positions in a company. [15]

Although not often identified explicitly in legislation, and sometimes explicitly excluded from qualifying as beneficial owners in the case of ordinary companies, senior managing officials (SMOs) are the most relevant individuals in SOEs, alongside government officials. SMOs are the individuals exercising control over the organisation, and their powers or appointment are usually mandated by law. Deciding which SMOs to include in beneficial ownership declarations will depend on policy aims and local organisational structures, but it is recommended to include executive-level managers as well as board-level positions.

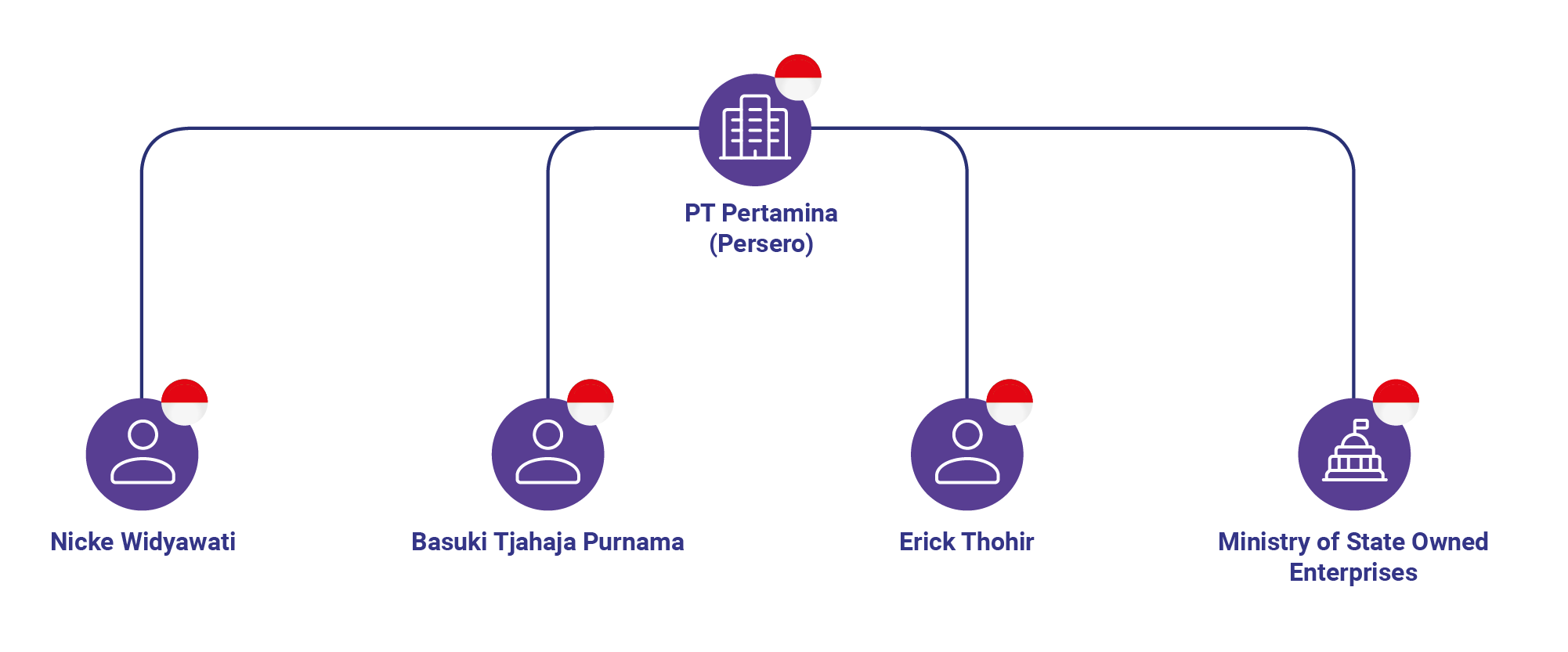

Public information on SMOs in Pertamina’s case shows the positions of the CEO, the Board President (also the CEO in this instance) and the President Commissioner. A more comprehensive approach would be to also list all members of the executive board and oversight commission.

Mapping the senior officials and government ministry which exert control over Pertamina

As part of the wider mapping exercise of Pertamina, the Ministry of State Owned Enterprises and the Minister Erick Thohir are also shown here. Nicke Widyawati is the CEO and Chair of the Board, and Basuki Tjahaja Purnama is the President Commissioner at the time of writing.

As information about the control of SOEs can be found in a range of legislative instruments, a comprehensive review of relevant legislation should be undertaken to identify SMOs. The source of this information will vary across jurisdictions. For example, NNPC is required by recent specific legislation on the petroleum industry in Nigeria [16] to have two ministers on its board during the period that it is wholly government-owned. Previously, this type of detail was found in the statute that created NNPC. In Indonesia and in the case of Pertamina, the legislation specifies that it is the responsibility of a particular minister to appoint the SMOs [17] alongside other oversight powers which are granted through legislation on the remit of the Ministry of State Owned Enterprises.

Relevant control mechanisms for SOEs

When establishing which control mechanisms to record, consideration should be given to the following:

- Board members and their appointment process

- Senior managing officials

- Role of government officials

- Control by legal framework

- Other influence and control

These types of control can all be captured within the Beneficial Ownership Data Standard (BODS), [18] an open standard developed and managed by Open Ownership and Open Data Services. [19]

Endnotes

[13] EITI, EITI Requirement 2.6 – State participation and state-owned enterprises: Guidance Note, 4.

[14] EITI, EITI Requirement 2.6 – State participation and state-owned enterprises: Guidance Note.

[15] E.g. “...there shall be entered… as its beneficial owners… the names of the one or more natural persons who hold the position of senior managing officials of the relevant entity” (Republic of Ireland (2019), S.I. No. 110/2019 - European Union (Anti-Money Laundering: Beneficial Ownership Of Corporate Entities) Regulations 2019, Article 5, paragraph 4. Retrieved from https://www.irishstatutebook.ie/eli/2019/si/110/made/en/print.

[16] Federal Republic of Nigeria Official Gazette, Petroleum Industry Act, 2021, Section 59, (2), (d)-(e), 51.

[17] Presiden Republik Indonesia, Undang-Undang Republik Indonesia Nomor 19 Tahun 2003 Tentang Badan Usaha Milik Negara, Chapter 2, GMS Authority, Article 14, 7; Article 15, 8; Article 27, 10-11.

[18] Open Ownership (n.d.), Beneficial Ownership Data Standard (v0.3). Retrieved from https://standard.openownership.org.

[19] Open Data Services (n.d.), Home page. Retrieved from https://opendataservices.coop.

Next page: Deciding whether to list individuals or role titles