Defining and capturing information on the beneficial ownership of investment funds

Introduction to investment funds

An investment fund generally refers to any type of collective scheme that pools together money from individuals, institutions (such as companies), or both to invest in different types of assets. The relevant details for investors to consider are described in one or more formal fund documents, such as a prospectus, which are typically filed with a designated authority, such as a jurisdiction’s securities and exchange commission or financial services authority. The different types of investment funds, the legal forms through which they are organised, the involvement of various intermediaries, and variations in the types of assets they can hold all introduce complexities when it comes to determining the beneficial owners of investment funds.

In retail investment funds, thousands of investors may be involved via intermediaries, and they may have little or no control of the fund’s activities or knowledge about the identities of other investors. The potential number of investors in a private investment fund is typically smaller than retail funds. Private investment funds tend to target high-net-worth individuals, including politically exposed persons, and fund managers may have a close relationship with their client investors. [6] A third classification is for actively managed funds that embrace a more aggressive strategy for buying and selling assets, versus passive funds that are, for example, indexed to the long-term performance of a large number of companies. Passive funds have been growing in their market share, and in some jurisdictions they hold a significant portion of ownership in publicly traded companies. [7]

Types of investment funds

There are many different classifications for investment funds. For example, some are closed-end, meaning they have a fixed number of shares or capital, whilst others are open-end, meaning they can grow into unlimited shares or capital. The number and types of investors that may be involved in a fund, which is most relevant to understanding its beneficial ownership, are generally shaped by the following classification:

a) Retail investment funds, which are available for any person to invest in. Many exchange-traded funds, pension funds, and mutual funds, referred to as undertakings for collective investment in transferable securities or the Undertakings for Collective Investment in Transferable Securities (UCITS) Directive in the EU, are examples of retail investment funds.

b) Private investment funds (or alternative investment funds), which are only available to specific categories of investors that may exist in a jurisdiction, such as advised investors, high-net-worth investors, certified or self-certified sophisticated investors, and restricted investors. [8] Hedge funds, private equity funds, venture capital funds, and family offices are examples of private investment funds. Rotating savings and credit associations are also sometimes used to pool funds for private investment, such as Stokvels, Chamas, and Gam’eya.

Legal forms of investment funds

Whilst an investment fund may be created using different types of corporate vehicles, they are usually organised as limited partnerships, trusts, or companies. According to the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), various legal forms are used for investment funds in different countries:

In Canada and the United States, for instance, both companies and trusts are used for investment funds. In Australia, New Zealand and Japan, the trust is the predominant form […] In many European countries, both joint ownership vehicles (such as fonds communs de placement) and companies (such as sociétés d’investissement à capital variable) are commonly used.

As another example, in the United Kingdom (UK), certain limited partnerships are often used as private investment vehicles for investing in assets such as real estate. Limited partnerships are an attractive corporate form to investors due to their flexibility and the fact that limited partners are passive investors who are not involved in the partnership’s routine management, thus minimising their liability. According to the British Private Equity & Venture Capital Association (BVCA), “[u]nlike in a private company (where shareholders of the same class have to be treated equally), the partners [in a limited partnership] can set the rules on matters such as how the profits are shared, how interests in the partnership are transferred and how the business is to be conducted.” [11]

Types of assets held by investment funds

Investment funds allow investors to own, control, and benefit from physical (or real) assets, such as land, gold, commodities, and infrastructure projects, or financial assets, such as shares of public companies listed on a stock exchange, shares of private companies, debt issued by corporations or countries, and indexes. Financial assets can be bought and sold freely through regulated exchanges or over the counter through private transactions involving a specialist dealer or broker. The beneficial ownership of a corporate vehicle operating as an investment fund is not necessarily the same as the beneficial ownership of the fund’s underlying asset.

Investment funds can also hold complex financial instruments offered through derivatives markets, such as options, swaps, and futures. The pricing, risk, and terms of derivatives are based on an underlying asset, and they allow investors to hedge a position, increase leverage, or speculate on an asset’s change in value. [12] For example, an investor might own both a stock and an option on the same stock that allows them to sell it at a set price; therefore, if the stock’s price falls, the option still retains value, reducing the investor’s losses. The increased use of derivatives has been a significant development in financial markets and can further complicate the identification of ultimate beneficial owners, as discussed below. Whilst considered, given the focus of this briefing on the BOT of corporate vehicles, a full treatment of the beneficial ownership of assets is outside its scope.

Intermediaries in investment funds

An investment fund serves as a conduit to benefit from one or more assets being held as investments. Investors can be individuals, corporate vehicles, or institutions, and there are usually a number of intermediaries between the investor and investment fund as well as between the investment fund and the underlying financial assets, especially if the fund’s units are exchange-traded (Box 1). This creates complexity when determining who exercises ownership or control at various points in the chain, and who is ultimately benefiting from the fund’s activities.

Depending on its legal form and structure, the individuals exercising control of an investment fund itself can differ from the individuals who own and benefit from the underlying assets being held by the fund at any given point in time, either directly or indirectly. Both retail and private investment funds typically have fund managers or advisors who make investment decisions for the fund, selecting securities that align with the fund’s objectives and risk tolerance. They conduct research, analyse market conditions, and aim to make informed decisions to maximise the fund’s performance. Reporting requirements vary, and fund managers may not need to be registered or licensed.

A single asset management company may oversee many investment funds. In this case, managers are typically employees who make decisions about the acquisition and disposal of assets in the funds for which they are responsible and who may benefit from a fund’s performance, for example through a bonus. Managers typically use funds to trade securities or engage in other transactions through which financial assets may only be kept for a very brief period of time on investors’ behalf, sometimes as little as a few seconds.

Box 1. Intermediaries involved in the management of investment funds [13]

Brokers and dealers act as intermediaries between investors and the fund, facilitating the buying and selling of fund shares. They connect investors with the fund’s shares and execute trades on their behalf.

Transfer agents manage the registration and transfer of fund shares, maintaining a record of shareholders, processing ownership changes, and issuing proxy materials for shareholder meetings.

Custodians act as a trusted third party, safeguarding the fund’s assets, including stocks, bonds, and other securities. They maintain accurate records of the fund’s holdings and ensure their safekeeping in a secure vault or depository. Often a bank, a custodian is the most likely actor to run checks on an investor’s identity and the origin of their money; however, these checks may not extend to the beneficial owners, where the investor is a company.

Central securities depositories are specialised financial institutions or organisations that play a crucial role in the operation and management of traded investment funds, providing essential services that ensure the safekeeping, settlement, and transparency of securities transactions. They act as trusted intermediaries between investors, investment funds, and other market participants, facilitating efficient and secure investment activities.

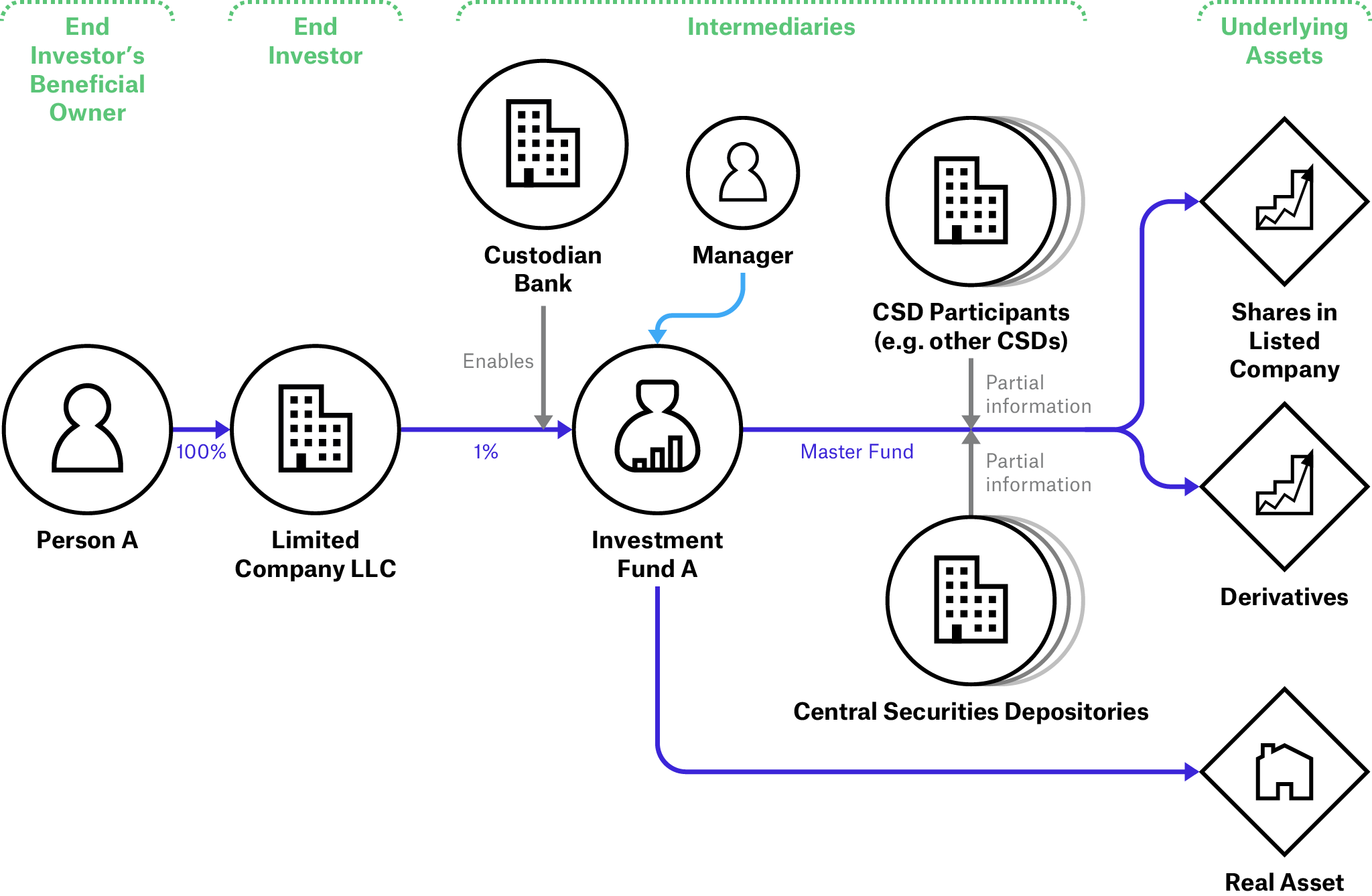

Figure 1. Illustration of intermediaries’ involvement in an investment fund and its financial assets

In Figure 1, Person A uses “Limited Company LLC”, of which Person A is the sole beneficial owner, to hold an interest in Investment Fund A. Investment Fund A invests in real estate and financial assets in the form of derivatives and shares in a PLC. In the middle, different types of intermediaries are involved. A custodian bank allows Limited Company LLC to invest in Investment Fund A, and central securities depositories hold registers of the ownership of securities, including shares in PLCs and exchange-traded derivatives. Each of these intermediaries holds partial information about various parties in the chain and investment ownership, making it difficult for each of them to know the identity of Limited Company LLC’s beneficial owners, the financial assets ultimately held by them, and all the intermediaries involved.

General legal and regulatory frameworks for investment funds

The investment industry is highly regulated in most countries. The existing regulations of the sector and securities trading are primarily intended to protect current and potential investors. [14] They ensure that investors are aware of the risks associated with their investments; help maintain the integrity of the market for investments and securities; and guard against fraud. Whether and how investment funds are subject to additional regulations, for example to combat money laundering, differs significantly between jurisdictions.

In some jurisdictions, the agency responsible for implementing laws and regulations governing investment funds is also responsible for implementing BOT. For example, the Securities and Exchange Commission of the Philippines is the national government regulatory agency charged with supervision over the corporate sector, including maintaining the country’s central BO register. It also oversees “capital market participants, the securities and investment instruments market, and the protection of the investing public.” [15]

Regulatory regimes in the United States and the European Union

The US has the largest investment fund industry in the world, with its managed fund assets amounting to around USD 32 trillion in 2022. [16] The EU follows with approximately USD 19 trillion under the management of investment funds, as of 2021. [17] In the US, the Investment Company Act of 1940 is the main legislation that imposes substantive requirements on investment funds’ organisation and operation, and the US Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) issues rules for the effective regulation and management of both retail and private investment funds. These rules are again mainly designed to protect investors by increasing transparency, integrity, competition, and efficiency in the investment and securities market. This includes measures such as requiring private fund advisers to provide quarterly statements to investors detailing certain information regarding fund fees, expenses, and performance, and obtaining and distributing to investors an annual financial statement audit of each private fund it advises. [18]

In the EU, the industry is mainly regulated by two Directives: the UCITS Directive and the Alternative Investment Funds Manager Directive (AIFMD). [19] The UCITS Directive covers mutual funds and lays down uniform rules, such as allowing for cross-border offerings as well as mandating certain information for investors to make it easier to understand the product in which they are investing. The AIFMD covers private (or alternative) investment funds, and lays down rules for authorising, supervising, and overseeing the managers of these funds. The bodies charged with implementing these Directives vary among member states and include, for example, securities and exchange regulators and tax agencies.

The US and the EU’s AML requirements for investment funds differ significantly, with implications for their oversight. In 2015, the EU passed the fourth Anti-Money Laundering Directive, which considers investment firms a financial institution and therefore renders investment advisers subject to the same AML standards as banks and other reporting entities, including measures such as customer due diligence (CDD) checks. At the time of writing, a new AML package including the sixth Anti-Money Laundering Directive was being drafted, and will aim to ensure the consistent identification of beneficial owners of UCITS and alternative investment funds with or without a legal personality by introducing a harmonised definition. [20] In contrast, the US’s AML regime, as set out in the Bank Secrecy Act, does not require investment advisers of private funds to maintain AML programmes. Several types of investment companies are also exempt, though AML requirements are in place for most retail funds. [21] At the time of writing, new rules were being contemplated in the US to strengthen AML requirements for private investment advisers. [22]

Footnotes

[6] Lakshmi Kumar, Private Investment Funds in Latin America: Money Laundering and Corruption Risks (Washington, DC: Global Financial Integrity, 2022), 1, https://gfintegrity.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/12/GFI-PIF-in-LatAm-Report.pdf.

[7] “Stealth socialism”, The Economist, 17 September 2016, https://www.economist.com/finance-and-economics/2016/09/17/stealth-socialism.

[8] These are the categories of investors classified by the Financial Conduct Authority (FCA) in the UK. See: “COBS 4.12B.38R – COBS 4.12B Promotion of non-mass market investments”, FCA Handbook, FCA, 1 February 2023, https://www.handbook.fca.org.uk/handbook/COBS/4/12B.html#D462937.

[9] “About Stokvels”, National Stokvel Association of South Africa, n.d., https://nasasa.co.za/about-stokvels/.

[10] OECD, “The Granting of Treaty Benefits with respect to the Income of Collective Investment Vehicles”, in Model Tax Convention on Income and on Capital 2017 (Full Version) (Paris, OECD Publishing, 2019), 9, https://doi.org/10.1787/53f97409-en.

[11] “The importance of UK Limited Partnerships for Private Equity & Venture Capital”, BVCA, n.d., 4, https://www.bvca.co.uk/Portals/0/Documents/Policy/Technical%20Publications/180822%20UK%20LP-PE%20brief%20(web%20version).pdf?ver=2018-08-22-160016-000.

[12] Kristina Zucchi, “Derivatives 101”, Investopedia, 23 August 2022, https://www.investopedia.com/articles/optioninvestor/10/derivatives-101.asp.

[13] Figure and text adapted from: Knobel, Beneficial ownership in the investment industry, 10.

[14] Knobel, Beneficial ownership in the investment industry, 10.

[15] “Mandate, Mission, Values, and Visions”, Securities and Exchange Commission, Republic of The Philippines, n.d., https://www.sec.gov.ph/about-us/mandate-mission-values-and-vision-2/#gsc.tab=0.

[16] See: Statista, “Total net assets of regulated open-end funds worldwide from 2012 to 2022”; Statista, “Managed assets in investment funds worldwide in 2022, by region”.

[17] The data for Europe is from 2021, as no statistics are available for 2022. See: “European investment fund assets value at the end of 2021, by country”, Statista, 1 February 2023, https://www.statista.com/statistics/368613/europe-value-investment-funds-assets-by-countries/.

[18] U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission, “SEC Enhances the Regulation of Private Fund Advisers”, Press Release, 23 August 2023, https://www.sec.gov/news/press-release/2023-155.

[19] European Union Law, “Directive 2009/65/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 13 July 2009 on the coordination of laws, regulations and administrative provisions relating to undertakings for collective investment in transferable securities (UCITS)”, Official Journal of the European Union, EUR-Lex, 17 November 2009, https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=celex%3A32009L0065; European Union Law, “Directive 2011/61/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 8 June 2011 on Alternative Investment Fund Managers and amending Directives 2003/41/EC and 2009/65/EC and Regulations (EC) No 1060/2009 and (EU) No 1095/2010”, Official Journal of the European Union, EUR-Lex, 1 July 2011, https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=celex%3A32011L0061.

[20] General Secretariat of the Council of the European Union, “Proposal for a Regulation of the European Union Parliament and of the Council on the prevention of the use of the financial system for the purposes of money laundering or terrorist financing”, European Council, 13 February 2024, 248, https://data.consilium.europa.eu/doc/document/ST-6220-2024-REV-1/en/pdf.

[21] Hanichak et al., Private Investments, Public Harm.

[22] FinCEN, US Treasury, “Financial Crimes Enforcement Network: Anti-Money Laundering/Countering the Financing of Terrorism Program and Suspicious Activity Report Filing Requirements for Registered Investment Advisers and Exempt Reporting Advisers”, Federal Register: The Daily Journal of the United States Government 89, no. 32: (February 2024), https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2024/02/15/2024-02854/financial-crimes-enforcement-network-anti-money-launderingcountering-the-financing-of-terrorism.