Early impacts of public beneficial ownership registers: Slovakia

Case study: Váhostav-SK

Public procurement for construction in Slovakia has historically been opaque and suboptimal, with companies previously bidding for work with low estimates resulting in bankruptcy and half-finished projects.

Slovakia’s largest construction firm, Váhostav-SK, faced bankruptcy in 2015, and its restructuring risked leaving hundreds of subcontractors largely unpaid. The police investigated Váhostav-SK, which had won several large state contracts for highway construction. Prime Minister at the time, Robert Fico, said in a press conference that it was not uncommon for Slovak construction companies to respond to the former government’s demand for cheap highways and bid as much as 60% less than the estimated cost by expert opinion.[1] In the Váhostav-SK case, companies ended up struggling to pay subcontractors, many of whom were small businesses.[2] Owing €104.68 million to hundreds of small and medium enterprises (SMEs), Váhostav-SK initially offered to pay a total of €15.7 million (15%) over a five-year period as part of its restructuring plan,[3] whilst the Slovakian Government proposed to buy up the remainder of the debt.

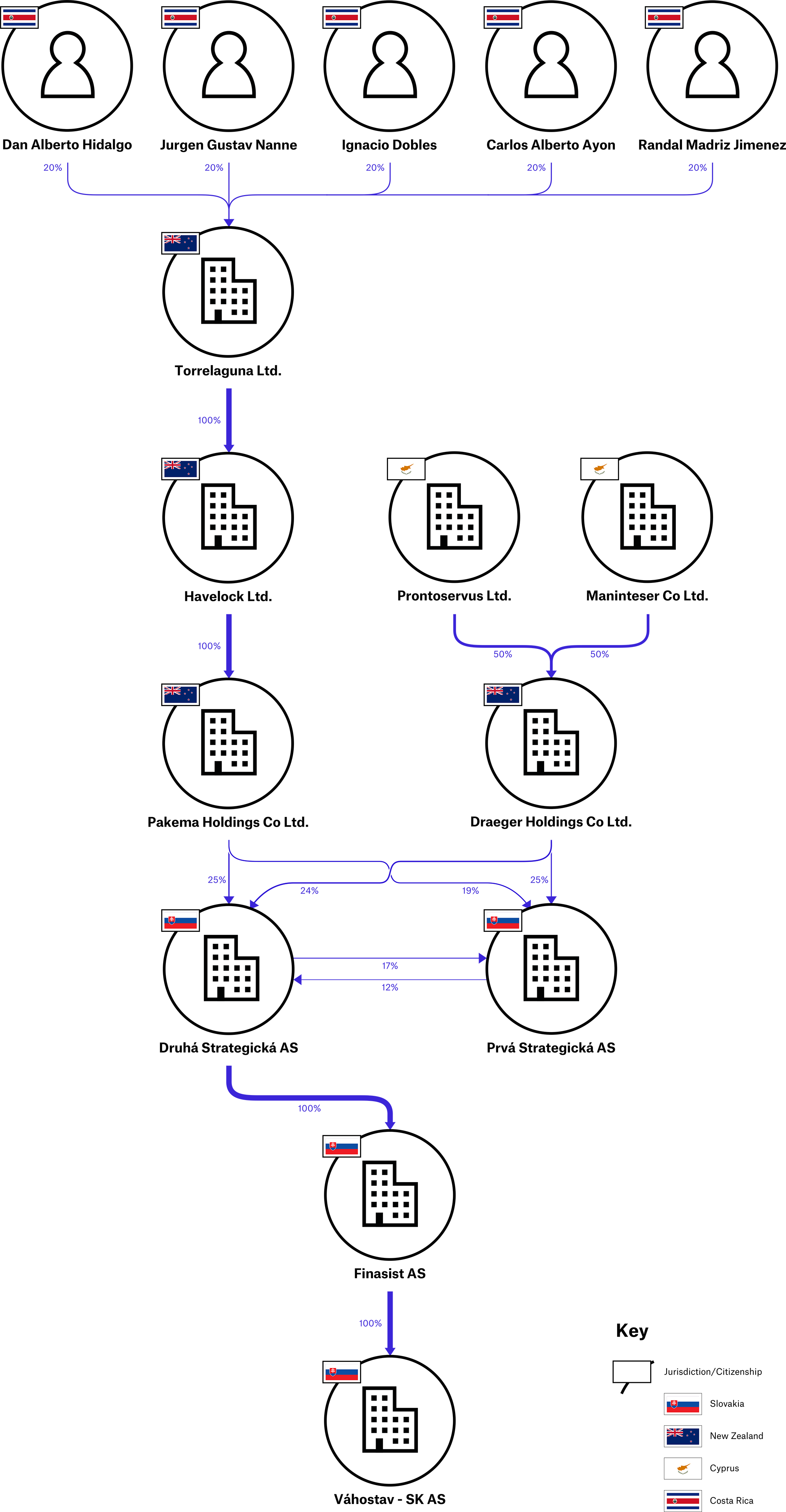

Transparency International Slovakia, in cooperation with Bisnode data company, uncovered the complicated ownership structure of Váhostav-SK, which led to shell companies in New Zealand and Cyprus as well as five private persons based in Costa Rica.[4] In response, opposition MPs filed a criminal complaint about the restructuring of Váhostav-SK, citing concern that claims were being registered from ‘fictitious [shell] companies.’ An opposition party chairman also noted that during the process of restructuring five shell companies had been created. There was a serious suspicion that the creditors included companies that had channeled state payments so Váhostav-SK would not need to fully pay its debts.

Figure 1. Vahostav beneficial ownership structure in 2015

Váhostav-SK ownership structure in 2015 according to Transparency International Slovakia and Bisnode research. Source: Transparency International Slovensko, Facebook, 26 March 2015.

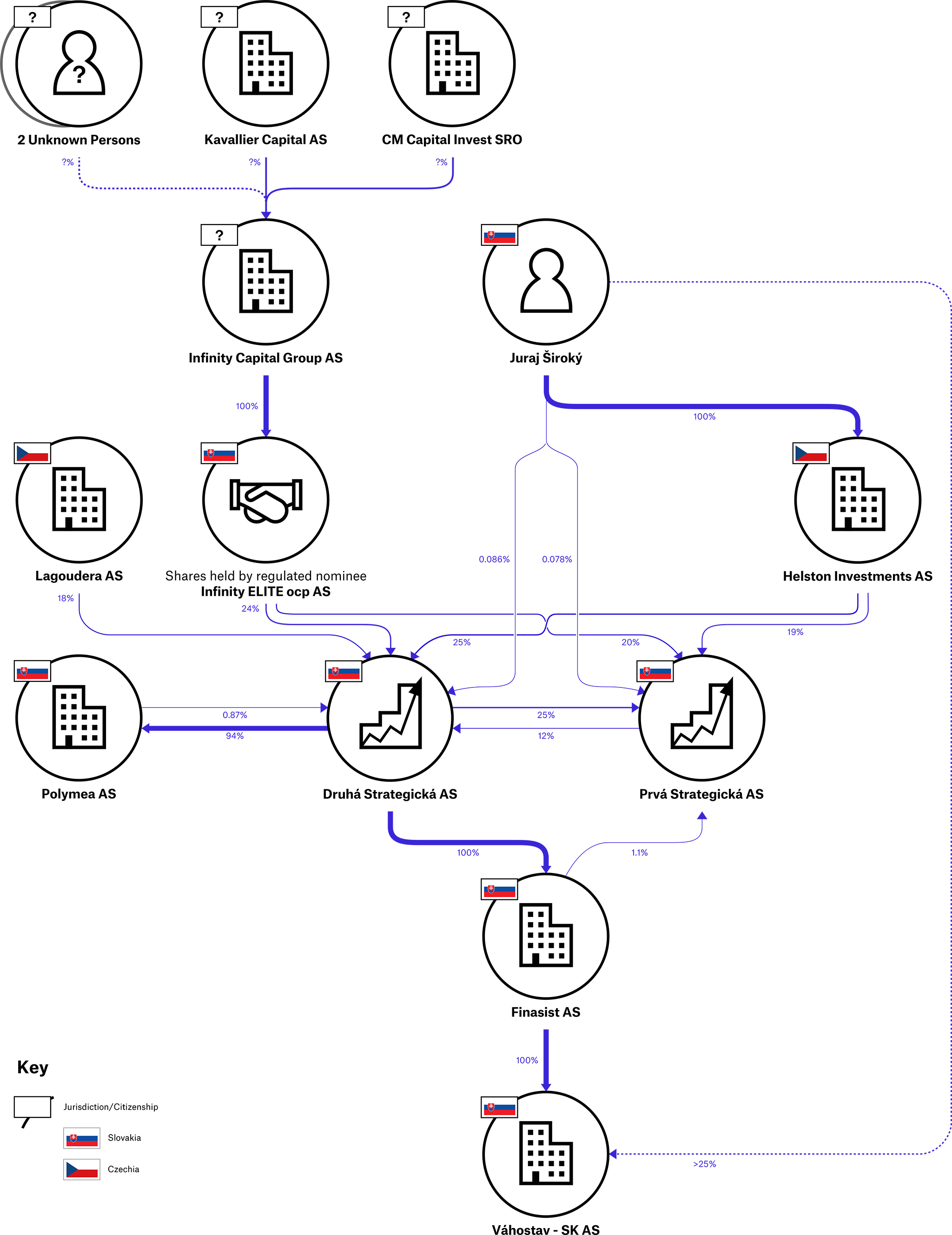

An alleged sponsor of the Prime Minister’s Smer party, Juraj Široký, was reported to hold a controlling interest in Váhostav-SK and potentially be behind the shell companies. This raised conflict of interest questions around the government’s investigations[5] and suspicions that Široký could be paid out himself in the government bailout, potentially at the expense of all the SME creditors.[6]

The Váhostav-SK case led to calls to establish a beneficial ownership register for companies receiving public funds.[7] In November 2015, The Register of Public Sector Partners was set up with the aim of revealing the management and ownership structures of companies entering contractual relationships with the public sector.[8] In 2017, Váhostav-SK was fined for misrepresenting its ownership, and the true beneficial owner turned out to be Juraj Široký, as confirmed in the company’s disclosure to the register that year. The company maintains that Široký was not an owner in 2015 and only acquired his ownership later.[9] The latest disclosure to the register from April 2020 shows an ownership structure that remains vague and complicated, although there is a noticeable difference in terms of the information that is available, the level of detail and how accessible it is, in addition to the fact that it is now fully clear how Juraj Široký exercises ownership and control over Váhostav-SK, meaning that the events from 2015 are less likely to repeat themselves.[10]

Figure 2. Vahostav beneficial ownership structure in 2020

Váhostav-SK ownership structure in 2020 according to the register, showing the ownership and control relationship between Juraj Široký and Váhostav-SK. (Source: Slovak Republic Register of Public Sector Partners, VÁHOSTAV - SK, a.s. verification document, 24 April 2020. Accessible at: https://rpvs.gov.sk/rpvs/Partner/Partner/Detail/9678)

Footnotes

[1] The Slovak Spectator, “Small businesses cut out in Váhostav case”. 2 April 2015. Available at: https://spectator.sme.sk/c/20056770/small-businesses-cut-out-in-vahostav-case.html [Accessed 24 June 2020].

[2] Ibid

[3] Ibid

[4] Transparency International Slovakia, “How to Make Beneficial Ownership Register Work: Lessons from the Slovak Beneficial Ownership Register”. December 2017. Available at: http://transparency.sk/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/HOW-TO-MAKE-BENEFICIAL-OWNERSHIP-REGISTER-WORK-_fin.pdf [Accessed 24 June 2020]; The Slovak Spectator, “Small businesses cut out in Váhostav case”. 2 April 2015. Available at: https://spectator.sme.sk/c/20056770/small-businesses-cut-out-in-vahostav-case.html [Accessed 24 June 2020].

[5] Prime Minister Fico did distance himself from Široký during the 27 March press conference. (FinWeb, “Kráľ štátnych zákaziek. To je legendami opradený Široký”. 2 December 2014. Available at: https://finweb.hnonline.sk/financie-a-burzy/538015-kral-statnych-zakaziek-to-je-legendami-opradeny-siroky [Accessed 24 June 2020].)

[6] The Slovak Spectator, “Small businesses cut out in Váhostav case”. 2 April 2015. Available at: https://spectator.sme.sk/c/20056770/small-businesses-cut-out-in-vahostav-case.html [Accessed 24 June 2020].

[7] Transparency International Slovakia, “How to Make Beneficial Ownership Register Work: Lessons from the Slovak Beneficial Ownership Register”. December 2017. Available at: http://transparency.sk/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/HOW-TO-MAKE-BENEFICIAL-OWNERSHIP-REGISTER-WORK-_fin.pdf [Accessed 24 June 2020].

[8] The Slovak Spectator, “Register of Public Sector Partners – brief overview on duties for foreign recipients of public funds”. 26 November 2018. Available at: https://spectator.sme.sk/c/20967942/register-of-public-sector-partners-brief-overview-on-duties-for-foreign-recipients-of-public-funds.html [Accessed 24 June 2020].

[9] The Slovak Spectator, “Tycoon Široký is the real owner of Váhostav”. 18 2015. Available at: https://spectator.sme.sk/c/20436124/tycoon-siroky-is-the-real-owner-of-vahostav.html [Accessed 24 June 2020].

[10] https://rpvs.gov.sk/rpvs/Partner/Partner/Detail/9678; https://rpvs.gov.sk/rpvs/Partner/Partner/Dokument/111291