Guide to drafting effective legislation for beneficial ownership transparency

Components of effective legislation

The following section highlights different components that should be found in BOT legislation, sequenced in the order these would usually be found in a law.

Policy objectives and purpose of the legislation

The purpose of a bill is its anchor, and it should be identified clearly at the beginning of proposed legislation or the preamble (the introductory part of a law that indicates its purpose and intent). Simply put, the purpose states the policy objectives that underpin the substantive provisions in the legislation.

The policy details should be established prior to drafting legislation. The policy process preceding legislative drafting can include the drafting of policy papers, commissioning impact assessments, [24] and conducting broad consultations. Consultations should include government departments – especially those that will collect the data (such as corporate registries); trust registries (such as tax authorities or the judiciary); and potential users of the data (such as procurement authorities, anti-corruption agencies, financial intelligence units (FIUs), and mining or extractive licensing agencies). Beyond government stakeholders and the private sector, any additional users of the data – such as civil society organisations (CSOs) and non-governmental organisations (NGOs) – and the general public should be consulted. [25]

Consultations can help define and broaden the policy goals for BOT reforms. These policy goals can then inform the drafting of certain elements of the legal framework, such as who will be given access to the information and what specifically they will have access to. For example, if a government’s policy goals are to improve transparency and accountability in public procurement and to improve citizens’ trust in the government, this would necessitate and justify providing access for the public to a subset of BOI. Conversely, a narrow purpose – such as pursuing the specific policy objective of fighting money laundering – would necessitate access to law enforcement agencies and competent authorities, as well as making it more difficult to justify broad access. There are a range of policy objectives to which BOT can contribute, and it is important for governments to identify all relevant objectives and to specify these in law.

The implementation of a BO register may face legal challenges, especially where access to personal data held by registers is provided to a broad range of users beyond government in order to maximise the impact of the reforms. This underscores the importance of balancing the need to safeguard individual privacy rights. In the case of legal challenges, courts will look at whether the measures are necessary and proportionate to achieving the stated objectives. Ideally, these should be anchored in broad terms in the public interest whilst covering specific voluntary commitments and binding obligations, such as those in the EITI Standard, Open Government Partnership action plans, the FATF Recommendations, and the UNCAC. Broadly, these can include:

- providing transparency, accountability, and oversight: for example, over natural resources or public spending;

- deterring and tackling illicit activities: including corruption, tax evasion, organised crime, money laundering, and terrorist and proliferation financing;

- creating a well-functioning business environment: for example, to regulate competition and improve public service delivery; encourage inward investment; and improve domestic resource mobilisation.

Box 5. Country examples: Kenya, Namibia, the United Kingdom, and the United States

In 2022, Kenya amended its legislation through the Companies (Beneficial Ownership) Regulations to include specific provisions on the use of BO data in public procurement. [26] This Regulation is accompanied by an explanatory memorandum that provides a background to the reforms, places them in the legislative context, and clearly states the policy objective for the amendment and what it intends to achieve. The memorandum also contains insights into the consultative process and various parties that were consulted. The memorandum states:

The Government is committed towards the growth and transformation of Kenya through vision 2030 with the firm emphasis on transparency, accountability and public participation and transformation of public procurement in Kenya. […] Transparency in […] Public Procurement is vital and […] the public disclosure of information of the people behind the entities that have been awarded tenders by the public procuring entities is crucial because it aids in identifying and reducing cases of mismanagement, fraud and corruption. This background necessitated the formation of the published Regulations entitled the Companies (Beneficial Ownership Information) Regulations, 2022 [emphasis added]. [27]

The policy objective is to improve transparency and accountability in public procurement, and there is a recognition of the role of public participation in achieving this. There is also a clear indication that although the information in the BO register is not accessible to the public, public access to information about the beneficial owners behind the corporate vehicles that are awarded tenders is necessary for the government’s broader objective to be achieved. This demonstrates how a clear set of objectives can inform specific elements of BO legislation, such as access.

The memorandum also articulates the government’s intention for amending the legislation, which is “to make the public procurement process transparent as well as enable the government to publish important information about a company in matters of public interest [and] is to streamline some regulations to give better effect to the [Companies] Act[, 2015]”. [28]

This is an example of a clear statement of purpose following a consultative process. This will serve as guidance for various government agencies tasked with implementing the regulation.

In Namibia, the government legislated for BOT through a series of acts. Because these provisions are part of a wider set of amendments, the preamble specifying the purpose and intent of the legislation is therefore broad, speaking to the overarching goal of regulating companies or trusts doing business in the relevant country, and it does not contain any specific information on the broader policy objectives for BOT reforms. The preamble in the Trust Administration Act of 2023 states its objectives are:

To regulate the control and administration of trusts; regulate trustees and trust practitioners providing services relating to trusts; specify powers and functions of trustees in respect of trusts; to specify powers and functions of Master in respect of trusts; specify powers and functions of court in respect of trusts; to require Master and trustees to keep beneficial ownership registers and other registers relating to trusts; and to provide for incidental matters. [29]

It mentions the central BO register, held by the Master, but does not provide an indication of the policy objective that underpins the creation of a BO register for trusts, although the regulation and control of trusts should also extend to preventing their misuse.

The UK amended its Companies Act to include BOT provisions. The amending act – the Small Business, Enterprise and Employment (SBEE) Act 2015 – outlines its purpose broadly: “to make provision about the regulation of companies; to make provision about company filing requirements; to make provision about the disqualification from appointments relating to companies; to make provision about insolvency”. [30]

The specific policy objectives are further detailed in multiple policy documents, including a post-implementation review: “The objective of the register is to enhance corporate transparency and, thereby, to facilitate economic growth and help tackle misuse of companies”. [31]

For the UK’s ROE, the policy objectives are clearly stated in its impact assessment:

The overarching objective is to create a publicly available register of ultimate ownership to enhance the transparency around the owners and controllers of relevant entities which own or buy UK property. In doing so the objective is to:

- Deter and disrupt crime, by making it more difficult to use corporate vehicles in the pursuit of crime.

- Deter criminals from money laundering in the UK

- Preserve the integrity of the financial system

- Increase the efficiency of law enforcement investigations, particularly in relation to identifying and tracing the proceeds of crime

- Require the same transparency of the relevant overseas entities as of UK companies [32]

The legislative act for the ROE is more specific in its purpose than the SBEE Act, and does not reference broader policy objectives. It describes itself as: “An Act to set up a register of overseas entities and their beneficial owners and require overseas entities who own land to register in certain circumstances”. [33]

The United States (US) Corporate Transparency Act firmly anchors the law in the policy objective of national security:

beneficial ownership information collected under the amendments made by this title is sensitive information and will be directly available only to authorized government authorities, subject to effective safeguards and controls, to—

(A) facilitate important national security, intelligence, and law enforcement activities; and

(B) confirm beneficial ownership information provided to financial institutions to facilitate the compliance of the financial institutions with anti-money laundering, countering the financing of terrorism, and customer due diligence requirements under applicable law [emphasis added]. [34]

Other documents – including a “Memorandum on Establishing the Fight Against Corruption as a Core United States National Security Interest” – and secondary legislation clearly explain that in the US, national security is BOT’s primary policy aim. [35]

Legislative placement

Where jurisdictions legislate for BOT by amending existing laws, at the minimum the amending laws – rather than the laws they amend – should include the overarching objectives of the reforms. A broad purpose will provide a better legal basis for broader access to BOI. Primary and secondary policy objectives should be identified prior to drafting legislation, and further detail should be made publicly available and easily accessible, such as in policy papers, explanatory memoranda, consultations, impact assessments, and parliamentary or legislative deliberations.

Where countries legislate for BOT through a standalone law on beneficial ownership, policy objectives can more readily be included in the preamble. Regardless of what approach is taken, an effective legislative framework should be anchored in a clear set of policy goals that are communicated at the beginning of proposed legislation.

Defining the beneficial ownership of corporate vehicles in law

The purpose of establishing the legislative framework is usually followed by clearly defining what constitutes beneficial ownership. Definitions are a foundational element of any legislation, and they must be carefully considered and clearly drafted. Any ambiguity may lead to inconsistency in the information reported, making the reforms less effective. Beneficial ownership is a material, substantive concept – referring to de facto control over a corporate vehicle – and not a purely legal or quantitative definition. A key challenge in defining beneficial ownership in law is to capture its substantive nature. [36]

Fundamentally, the definition should state that a beneficial owner is a natural person, and should cover all relevant ways a natural person can exercise ownership or control over, or derive benefit from, any type of corporate vehicle, whether directly or indirectly. A good way to capture the substantive nature of beneficial ownership is to include a broad definition of what it constitutes, coupled with a non-exhaustive list of examples of ways in which beneficial ownership can be held, including a catch-all clause.

Any thresholds should be set sufficiently low so that all relevant individuals are included in declarations. [37] This should balance the need for more information with a higher compliance burden and the risk of collecting too much information, introducing noise [38] in the data and increasing the resources required to collect, store, and use it. All beneficial owners and all interest types should be disclosed. Legislation should be complemented by guidance on how to determine or calculate certain interests, including ownership and voting rights where such interests are indirectly held.

Often, a definition will also make reference to the corporate vehicles it will apply to. Defining which criteria constitute beneficial ownership will also determine whether a specific corporate vehicle can be beneficially owned. For a regime to be comprehensive, definitions should consider all forms of ownership and control in an economy, and all corporate vehicles with or without distinct legal personalities through or by which assets can be owned, benefitted from, and controlled. These corporate vehicles should be required to make declarations about their beneficial ownership.

BOT as a policy area has historically focused on private limited liability companies. Increasingly, countries are looking to include additional corporate vehicle types into the scope of disclosure. Whilst substantively the concept of beneficial ownership remains the same – the natural persons who ultimately own, control, or benefit from corporate vehicles – initial legal definitions have mostly been developed for ordinary limited liability companies. These definitions are not necessarily suited to apply the substantive notion of beneficial ownership to other corporate vehicles. For example, whilst employees are sometimes explicitly excluded from the definition of beneficial ownership for private limited liability companies, senior managing officials of state-owned enterprises (SOEs) may have powers or appointments mandated by law, and therefore have a high degree of control and, as such, should be considered beneficial owners of SOEs. [39]

Additionally, whilst the rights to control and economic benefits have historically been closely tied to ownership, these rights are increasingly being separated through legal instruments and arrangements. Therefore, it may be necessary to detail all of these interests separately in a legal definition. As BOT is being applied to an increasing number of types of corporate vehicles, there is a need to constantly reassess what beneficial ownership means as a substantive concept when applied to other entities and arrangements, such as trusts, SOEs, investment funds, and listed companies. Consequently, jurisdictions may be best served by including a single, unified, broad definition of beneficial ownership in primary legislation, in line with global standards. This definition should not be prescriptive to a level of detail that limits what constitutes beneficial ownership when applying the substantive concept of beneficial ownership to different corporate vehicles to certain interests that are specific to certain corporate vehicles. The latter can be detailed in secondary legislation.

In defining the beneficial ownership of corporate vehicles, it is also important to use guidance provided by international standards, such as those set by the FATF and the OECD. This can ensure consistency across jurisdictions, and adherence to these standards can enhance the interoperability of BO registers across BO-implementing countries, facilitating easier cross-border information sharing and cooperation. Legislators should be mindful that the objectives they are pursuing may be broader than those of certain international standards, which should therefore be considered as minimum standards to incorporate into reforms.

A unified definition helps to avoid confusion and facilitate compliance. In several countries, a beneficial owner is defined by several pieces of legislation, all of which may overlap and differ. For example in Zambia, the Banking and Financial Services Act, the Financial Intelligence Act, the Securities Act, the Public Procurement Regulations, and the Income Tax Act are some of the laws that define who a beneficial owner is. [40] Although the Public Procurement Regulations and the Income Tax Act refer to the definition in the Companies Act, the other laws provide varying definitions, and the threshold for ownership interest also differs. [41] A unified definition can be created by expressly adopting, consolidating, or amending definitions in existing legislation. Ideally, primary legislation will include a broad definition, with additional secondary legislation referring to this definition and specifying what the definition means when applied to certain corporate vehicles, such as companies, LLPs, or legal arrangements. This is to ensure coherence across legislation and enable compliance. It is also essential for any verification mechanisms that rely on AML-regulated parties to check entries on the register to function effectively, so that both the parties reporting information and those checking the information do so using the same definition.

Exemptions

Whilst some types of corporate vehicles, such as listed companies, may be exempt from the full disclosure requirements, excluding certain corporate vehicles from any type of disclosure can displace risk or create loopholes. Entities and arrangements exempt from disclosing their beneficial ownership should still be required to make declarations, including the basis for their exemption. Any exemptions from full declaration requirements should be clearly defined and justified, and reassessed on an ongoing basis. [42] Exemptions from disclosing beneficial ownership may be granted when an entity or arrangement is already disclosing sufficient information and this information is readily accessible (e.g. when listed companies are subject to disclose sufficient relevant information to a regulator). State-owned vehicles often do not meet these criteria, yet are exempted by many countries. Any exemptions should mention specific criteria (e.g. a list of stock exchanges) rather than constitute blanket categories. All exemptions should be interpreted narrowly.

Box 6. Country examples: Ghana, Kenya, the Netherlands, South Africa, and the United States

In the US, the governing law for BO disclosures is the Corporate Transparency Act (CTA), which is supplemented regulations in the form of a number of Beneficial Ownership Rules put in place by the Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (FinCEN), the US FIU and the agency responsible for implementing the reforms.

In 2021, the CTA was amended to include provisions on beneficial ownership. It defines a beneficial owner as follows:

(3) BENEFICIAL OWNER.—The term “beneficial owner”—

(A) means, with respect to an entity, an individual who, directly or indirectly, through any contract, arrangement, understanding, relationship, or otherwise

(i) exercises substantial control over the entity; or

(ii) owns or controls not less than 25 percent of the ownership interests of the entity; and

(B) does not include—

(i) a minor child, as defined in the State in which the entity is formed, if the information of the parent or guardian of the minor child is reported in accordance with this section;

(ii) an individual acting as a nominee, intermediary, custodian, or agent on behalf of another individual;

(iii) an individual acting solely as an employee of a corporation, limited liability company, or other similar entity and whose control over or economic benefits from such entity is derived solely from the employment status of the person;

(iv) an individual whose only interest in a corporation, limited liability company, or other similar entity is through a right of inheritance; or

(v) a creditor of a corporation, limited liability company, or other similar entity, unless the creditor meets the requirements of subparagraph (A). [43]

This definition covers who a beneficial owner is and who a beneficial owner is not, which helps reporting entities understand which individuals are relevant. Building on the CTA, FinCen’s Beneficial Ownership Information Reporting Requirements Rule defines the terms “substantial control” and “ownership interests”, and also includes a catch-all provision to ensure other forms of substantial control beyond those listed are captured. [44] The Rule also expands on the five exemptions in the CTA, including, for example, “minor child[ren]” and “individual[s] acting as a nominee, intermediary, custodian, or agent on behalf of another individual.”

During consultations on the regulations, it was argued that the CTA limits FinCEN to collecting BOI on a single person because the definition refers to “an” individual. For the avoidance of doubt, FinCEN clarified this in the Rules by indicating that the term “beneficial owner” refers to “any” person, and restricting a beneficial owner to one individual could not have been the intention of the legislature, seeing as their goal is to “prevent and combat money laundering, terrorist financing, corruption, tax fraud, and other illicit activity, while minimizing the burden on entities doing business in the United States”. [45]

In the Netherlands, the Money Laundering and Terrorist Financing Prevention Act has a broad definition of beneficial ownership in Article 1, considering a beneficial owner as a “natural person who is the ultimate owner of or has control over a client, or the natural person on whose behalf a transaction or activity is carried out”. [46] This definition is used throughout the Act to cover the Know Your Customer (KYC) and Customer Due Diligence (CDD) obligations of entities. Article 10a of the Act covers information about beneficial owners and adopts a definition broader than the AML framing of “clients” and “transactions”, specifying that in one paragraph the definition deviates from the earlier definition. It reads: “the natural person who ultimately owns or controls a company or other legal entity or a trust or similar legal arrangement”. [47]

The same article specifies which legal entities are covered by the term “company or other legal entity”. For the term “trust or other legal arrangements”, the Act refers to secondary legislation for the registration of ultimate beneficial owners of trusts and similar legal structures. BO disclosure requirements for legal entities are covered in the Companies Act, which refers to the definition in the AML act in Article 15a:

The company register records who the ultimate beneficial owner is or who are the ultimate beneficial owners of companies or other legal entities as referred to in Article 10a, second paragraph, of the Money Laundering and Terrorist Financing Prevention Act [emphasis added]. [48]

Separately, the regulations for the register of the beneficial ownership of trusts also defines an “ultimate beneficial owner as referred to in Section 10a(1) of the Money Laundering and Terrorist Financing Prevention Act” (emphasis added). [49]

A detailed definition of what criteria constitutes the beneficial ownership of both legal entities and trusts as well as other legal arrangements are in AML regulations, and this definition is applicable to both disclosure of beneficial ownership to the register, as well as financial institutions and designated non-financial businesses and professions conducting KYC/CDD checks. [50] This includes a catch-all clause by including BO through “other means”. [51]

As a result, the Netherlands has a harmonised definition of beneficial ownership. However, the specific criteria in the AML regulations are not comprehensive, and they follow the FATF’s cascading test intended for KYC/CDD, which may risk not all beneficial owners, or their interests, being comprehensively identified. [52] So whilst unified, it is not a robust definition for BO disclosure. In addition, some legal entity types are excluded from disclosure requirements, although obliged entities are required to conduct KYC/CDD checks on those legal entities.

Kenya also has a broad definition of beneficial ownership, applying generally to all types of corporate vehicles. This is in primary legislation, the 2015 Companies Act, where “‘beneficial owner’ means the natural person who ultimately owns or controls a legal person or arrangements or the natural person on whose behalf a transaction is conducted, and includes those persons who exercise ultimate effective control over a legal person or arrangement”. [53]

Kenya’s multiple BO regulations – of 2020, 2022, and 2023 for companies, and 2023 for partnerships – provide additional detail, including defining concepts like “significant influence or control” and “ultimately own or control”, and criteria and details on how beneficial ownership can be held, including specific thresholds. [54] It also includes a catch-all clause through the concept of “significant influence or control”:

(2) For the purpose of these Regulations, a beneficial owner of a company shall be a natural person who meets any of the following conditions in relation to the company—

(a) holds at least ten percent of the issued shares in the company either directly or indirectly;

(b) exercises at least ten percent of the voting rights in the company either directly or indirectly;

(c) holds a right, directly or indirectly, to appoint or remove a director of the company; or

(d) exercises significant influence or control, directly or indirectly, over the company. [emphasis added] [55]

Whilst this is good practice, the BO disclosure regulations are restricted to companies and partnerships rather than all corporate vehicles, although the phrasing in the primary legislation allows further regulations to be developed for other corporate vehicle types, without amendments to primary legislation.

Whilst most countries focus on the two prongs of ownership and control, Ghana has a more comprehensive definition in its 2019 Companies Act, also explicitly covering benefit. It states: “‘beneficial owner’ means an individual […] who has a substantial economic interest in or receives substantial economic benefits from a company whether acting alone or together with other persons” (emphasis added). [56]

Also see the example of South Africa in the section Approaches to legislative reform.

Legislative placement

The core elements of a definition should be in primary legislation. These elements include stating that a beneficial owner should be a natural person, including foundational concepts such as ownership and (effective) control, and may include deriving substantial benefit from a corporate vehicle which can be held directly or indirectly. A clear prohibition of certain parties (e.g. agents, custodians, intermediaries, or nominees acting on behalf of another person qualifying as a beneficial owner) can be included in primary or secondary legislation. Primary legislation should specify to which corporate vehicles the definition applies and can make a provision for exemptions. Details on exemptions can be prescribed in secondary legislation to enable their periodic revision. Secondary legislation can specify that where no individual meets the definition of a beneficial owner, the name of a natural person in a senior role with managerial responsibility for the corporate vehicle in question is provided, making clear that this person is not a beneficial owner. This should be supported by guidance which can include graphics, case studies, and examples.

In defining a beneficial owner, different variations of phrases such as “significant influence and control”, “ultimate control”, and “substantial economic interest” are often used. These phrases are subject to different interpretations, and whilst it is helpful to use broad phrases like these to capture the substantive nature of beneficial ownership, it is equally important to define these phrases. This could be done in secondary legislation to allow for the relevant authority to regularly review the definition and modify it if necessary.

Reporting obligations

The legislation should create obligations for reporting BOI, establishing the legal basis for collecting BO data, and clearly indicating:

- who has the responsibility to submit information;

- when information should be submitted;

- what information should be reported;

- how the information should be reported; and

- which authority the information should be reported to.

Who has the responsibility to submit information

The legislation should be very clear on the types of corporate vehicles the reporting obligations apply to and on whom the responsibility lies to submit the BOI. Generally, reporting obligations are placed on the corporate vehicle itself. As per international AML standards, many countries also require companies to hold and maintain registers of their own beneficial owners. [57] There may also be obligations on the beneficial owner to provide information to the company, as well as powers for the corporate vehicle to compel the beneficial owners to provide information on request and issue penalties for failures to comply. [58]

Box 7. Country examples: Denmark and the United Kingdom

The Companies Act in Denmark includes clear a obligation on the company to obtain information, and on beneficial owners to provide specific information to the company:

§ 58 a. The company must obtain information about the company’s beneficial owners, including information about the beneficial owners’ rights.

PCS. 2. Anyone who directly or indirectly owns or controls the capital company must, at the company’s request, provide the company with the information about the ownership relationship that is necessary for the company’s identification of beneficial owners, including information about the beneficial owners’ rights [emphasis added].59

In the UK, the Companies Act gives companies the power to give notice to individuals it has cause to believe are beneficial owners. It also places a duty on beneficial owners where “the person knows that to be the case or ought reasonably to do so” on supplying information. [60] It also provides powers to a company to issue a restrictions notice to an individual who fails to provide information and who holds a relevant interest. Following the issuing of such a notice, the individual cannot transfer the interest, nor exercisable rights in respect of the interest, among others. [61]

When information should be submitted

The legislation should specify which events should trigger the submission of information, or confirmation that the information held is correct, and specify a reasonably short, defined time period within which this needs to be done. These usually include:

- by a specific deadline for initial reporting in the legislation (e.g. six months from enactment) and, subsequently, as part of any new registration or incorporation;

- when there is any change in beneficial ownership, such as a change in the particulars of an existing beneficial owner, the cessation of beneficial ownership, or the addition of a new beneficial owner (jurisdictions have used time periods that range from as little as 7–14 days);

- upon the passing of 12 months, or together with annual statements.

In determining the appropriate reporting timelines, countries should consider their specific context and take into account their institutional setup and other domestic circumstances that may impact one’s ability to comply. Generally, the shorter the time period, the more up-to-date the information, and the more useful it is.

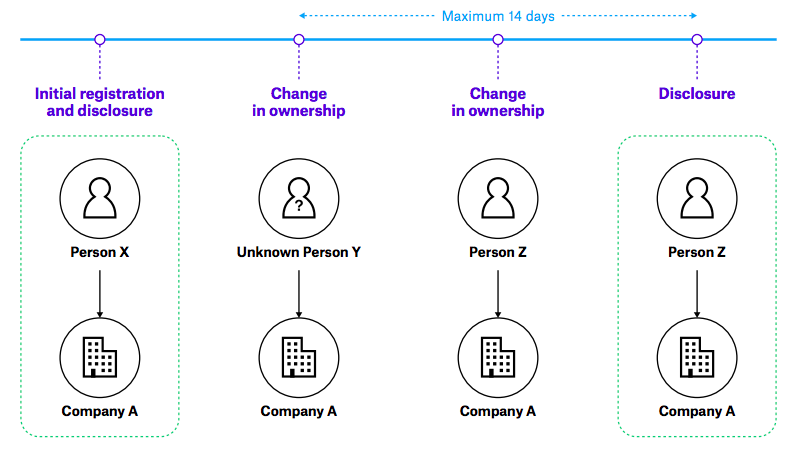

Following initial disclosure, all changes in beneficial ownership should be legally required to be reported to the central register in order to close a loophole explained below in Figure 2. Where companies hold their own registers in addition to the submission of information centrally, legislation should also require companies to retain the information for a certain number of years.

Figure 2. Reporting requirements loophole for changes in beneficial ownership

In this example, Company A has disclosed Person X to be its beneficial owner at initial registration. Later, Person Y replaces Person X as the company’s beneficial owner. The prescribed time period for reporting changes in this jurisdiction is 14 days. Within this time period, the beneficial owner of Company A changes again, from Person Y to Person Z. If there is no requirement to report all changes in BO, Person Y can legally avoid disclosure – and potentially exploit this for illicit purposes – provided that Person Z is disclosed as the beneficial owner within the prescribed time period of the first change in ownership. Source: Open Ownership. [62]

Box 8. Country examples: Denmark and Singapore

The Companies Act in Denmark specifies when companies need to submit information to the registrar, including reporting timeframes and which events should trigger reporting information:

PCS. 3. The company must register the information about the company’s beneficial owners, including information about the beneficial owners’ rights, in the Danish Business Authority’s IT system as soon as possible after the company has become aware that a person has become a beneficial owner. Any change to the information registered about the beneficial owners must be registered as soon as possible after the company has become aware of the change [emphasis added]. [63]

The Act also provides a requirement for annual confirmations, and to retain information:

PCS. 4. The company must at least once a year examine whether there are changes to the registered information about the company’s beneficial owners. […]

PCS. 5. The company must keep documentation for the information obtained about the company’s beneficial owners for 5 years after the beneficial ownership ceases. The company must also keep documentation for the information obtained about attempts to identify beneficial owners for 5 years after the completion of the identification attempt [emphasis added]. [64]

Singapore legislated reporting requirements through its 1967 Companies Act. [65] It complements the legislation with accessible guidance on the register’s website, stating clear timelines for keeping company BO registers, or Registers of Registrable Controllers (RORC), up to date:

Entities maintaining RORC must update the changes within:

- 2 business days after the particulars have been “confirmed”; or

- 2 business days after the end of 30 days after the date on which the notice is sent by the company to the registrable controller. [66]

In addition, it specifies when these changes need to be reported to the registrar, the Accounting and Corporate Regulatory Authority (ACRA):

Lodging RORC information with ACRA

All companies, foreign companies and limited liability partnerships (LLPs), unless exempted, are required to lodge their RORC information with ACRA. The information must be lodged with ACRA within two business days after the RORC has been set up.

Updating RORC information with ACRA

If there are changes to the RORC information of your entity, you must first update the information on your [RORC] maintained at your registered office address or at the address of your appointed registered filing agent (RFA). Following which, you must lodge the updates with ACRA’s Central Register of Controllers within two business days [emphasis in original]. [67]

What information should be reported

Legislation should clearly and exhaustively specify what information should be included in a declaration, particularly where this pertains to personal data. This should generally include sufficient information to identify the beneficial owner, the corporate vehicle, and the relationship between them. Sufficient information should be collected to be able to identify the individuals and corporate vehicles, and to allow the information to be verified. Some countries may choose to collect information about the individual making the declaration on behalf of the corporate vehicle. Implementers should also factor in specific requirements to collect information by various international standards, including the FATF and the 2023 EITI Standard. [68]

In determining what information to collect, it is also important for countries to carefully consider the needs of those who will use the information. This should include all parties that are able to use the information to achieve the stated policy objective. Users should be engaged throughout the implementation process, starting with consultations. For example, law enforcement agencies may require visibility of the full ownership structure of a company to facilitate establishing relationships between individuals, corporate vehicles, and assets in investigations. By implication, information about intermediaries, including other corporate vehicles and agreements, may need to be collected and mandated by law. Reliable identifiers should be collected for (or issued to) all individuals and corporate vehicles. [69]

It may be useful to include provisions for powers to amend the list of information. This is a way to future-proof legislation in light of the evolving nature of the BOT policy area and international standards, and the iterative approach to implementation to accommodate these changes.

Ultimately, the extent of information that a country chooses to collect should be driven by what is necessary to achieve their policy objectives and the needs of data users. Information required to be disclosed should be clearly and exhaustively enumerated in law and limited to what is necessary, in line with common requirements in privacy and data protection legislation.

Box 9. Country examples: Denmark and Zambia

The BO register in Zambia is run by PACRA. Sections 12(3)(e) and 30(1)(b) of Companies Act 2017 requires an intending company and existing companies to provide the following: “a statement of beneficial ownership which shall state, in respect of each beneficial owner— (i) the full names; (ii) the date of birth; (iii) the nationality or nationalities; (iv) the country of residence; (v) the residential address; and (vi) any other particulars as [may be] prescribed”, [70] among others.

This list does not include the information about the relationship between the beneficial owner and the company. It does contain a provision for powers to prescribe “any other particulars”, allowing this to be addressed in secondary legislation. The Companies (Prescribed Forms) and The Companies (General) Regulations in 2019 expand on this list to include: “(i) full names, (ii) date of birth; (iii) nationality; (iv) country of residence; (v) gender; (vi) residential address; (vii) number of shares owned; (viii) class of shares owned; and (ix) nature of beneficial ownership” (emphasis added). [71]

Therefore, primary and secondary legislation together include provisions to collect information about the beneficial owner and their relationship with the company.

In Denmark, secondary legislation clarifies which information should be reported through the executive order on registration and publication of information about owners in the Danish Business Authority:

§ 37. The registration of natural and legal persons associated with companies, foundations, associations as well as trusts or similar legal arrangements as owners must indicate full name, function in the company, [Danish social security] number, citizenship at birth, address and country of residence for natural persons or name, [Danish company] number and domicile of legal entities.

PCS. 2. If the natural person does not have a [Danish social security] number or the legal person does not have a [Danish company] number, the following must be stated:

1) For persons without a [Danish social security] number, information on date of birth, citizenship at birth, gender, passport number or number from a national identity card that can be used when entering a Schengen country, and the country of issue of the passport or the national identity card must be entered in connection with the registration as well as information about the relevant person’s tax identification number in their home country. A photo of a valid passport or national identity card that can be used when entering a Schengen country must be attached to the notification [emphasis added]. [72]

How the information should be collected

Information should be collected, ideally through online forms with accompanying guidance that includes illustrative diagrams of different ways in which BO can be held, and how indirect interests should be determined and calculated. Forms should be designed as a service informed by user needs and tested with actual users to facilitate and enable compliance, and should therefore be periodically reviewed. [73] To enable this, legislation should not include the forms themselves, but should define the information to be collected, as specified above.

Effective reforms would see a whole-of-government approach to BOT, working collectively towards a central repository of information on corporate vehicles. In some countries, however, other authorities may be legally required to collect BOI from certain corporate vehicles; for example, as part of procurement or licensing processes. In this case, it is imperative that the disclosure requirements are harmonised to the extent possible – including the forms used for collecting BOI to ensure uniformity in the information collected, and to lower the compliance burden. These types of requirements should be identified when other relevant legislation is considered, as previously discussed. Ideally, information collected should be checked against and consolidated with any existing BOI held in order to avoid a situation where a government may hold conflicting information on the beneficial ownership of a single corporate vehicle. As an alternative to various authorities collecting information and needing to consolidate it, corporate vehicles can be required to update their information held by the central register and provide an extract confirming this, including the BOI itself.

Which authority the information should be reported to

Reporting obligations should specify which authority the information should be reported to, i.e. the registrar. The following section provides more detail about this.

Legislative placement

Given that provisions on reporting obligations establish a legal basis for collecting information, such obligations should be in primary legislation. Specifically, the nature of the obligations, when information should be reported, and who is responsible for reporting should be in primary legislation. Given the fact that collecting BOI includes processing personal data, legislation should include an exhaustive list of details to collect, and these should be the minimum information required to meet the stated policy objectives; extraneous particulars should not be included. To enable an iterative approach, provisions delegating power to amend the list of particulars could be included. It is generally not recommended to include forms in legislation, as these may need to be amended, and the legislation should enable the design of the system, rather than inadvertently designing the system itself (see Designing systems and services through legislation in Common pitfalls). Reporting obligations should be clarified through guidance , ideally including example diagrams.

The registrar and the register

Legal basis for a central register

Legislation should form the basis for the establishment of a central register. Legislation should make it clear which authority should collect BOI in a central register, and provide the powers, mandate, and responsibility to this authority – the registrar – to establish and oversee a register. Different types of authorities can function as the registrar, such as corporate registries, tax authorities, FIUs, or regulatory authorities, such as securities commissions or central banks. Sometimes different authorities oversee registers for different types of corporate vehicles – e.g. legal arrangements such as trusts, or non-profit organisations – or for different administrative units in federated systems. In this event, the law should enable sufficient cooperation and exchange of information, ideally to allow the information to be centralised and integrated to create a comprehensive view of corporate vehicles.

It is not uncommon for different authorities or sector regulators to have a legal mandate to collect BOI for a specific purpose. For example, in Nigeria, apart from the Companies and Allied Matters Act, the Petroleum Industry Act requires the Nigeria Upstream Regulatory Commission to keep a BO register. Effective reforms require centralising information in order to work towards a single source of truth. Primary legislation can specify that other agencies, especially those that interact with or regulate companies, have a role in maintaining a central register. [74]

Information storage

The laws should specify how and for how long records should be kept, which should be a reasonable and specified number of years, including for dormant and dissolved corporate vehicles. International standards also include minimum information retention periods. [75] To ensure BOI can be effectively used, it should be collected, stored, and shared as structured and interoperable data as far as practically possible. [76] Primary legislation should not specify this in a great level of detail, but could place a responsibility on the registrar to ensure information is stored digitally in an organised, accessible, and usable way, and that both individuals and corporate vehicles can be uniquely identified via the collection and issuing of a reliable identifier. [77] Existing legislation, including data protection or laws governing public sector information, may have a bearing on these provisions.

Box 10. Country examples: Argentina, Ghana, and the United Kingdom

Ghana’s 2019 Companies Act establishes a central register of beneficial owners and specifies which information should be entered into the register. In addition, the law provides certain obligations for the registrar:

(3) The Registrar shall:

(a) collaborate with other authorities for [the] purpose of maintaining, verifying and updating the Central Register;

(b) on request and in a timely manner, make information entered in the Central Register available to the relevant authorities for inspection; and

(c) in line with open data best practices, make an electronic format of the Central Register available to members of the public for inspection [emphasis added]. [78]

The obligation in subsection 3(a) is useful for when information is collected by authorities other than the registrar. Arguably, this provision implies a mandate for the registrar to drive inter-agency coordination for the purpose of maintaining up-to-date and accurate information.

Subsection (3)(c) makes reference to “open data best practices”. [79] This places responsibilities on the registrar to ensure data is collected in a structured and standardised format, without prescribing in detail what that format should be.

Argentina passed Law 27.739 in March 2024. This law gives the federal tax administrator the authority and mandate to collect BOI, and ensure its accuracy, including specific functions and powers:

Article 28. The Federal Administration of Public Revenues (AFIP), an autonomous agency within the Ministry of Economy, will centralise, as the authority in charge of applying and enforcing the law, in a Public Registry of Beneficial Owners, the “registry” here onwards, the adequate, precise and up-to-date information referred to those human persons that are beneficial owners in the terms defined of Article 4 bis of the Law 25.246.

The Registry will comprise the information of the Information Reporting Regimes established by the AFIP for this purpose, as well as any other information that might be required by the authority of application to other public bodies. […]

Article 30. The authority will have the following functions and powers:

a) Incorporate and keep updated the information regarding final beneficiaries;

b) Receive information from the Financial Intelligence Unit (FIU) and other public organisations, for the identification, verification and incorporation of final beneficiaries into the registry;

c) Issue the complementary regulations necessary for the operation of the registry and for the receipt of information referring to final beneficiaries of other public organisations;

d) Sign agreements with other public organisations, in order to exchange information and carry out common actions linked to the purpose of the registry. [80]

In the UK, Part 35 of the 2006 Companies Act includes provisions about the functions and powers of the registrar. [81] The 2023 Economic Crime and Corporate Transparency Act extended the retention period for records about companies to 20 years after their dissolution. [82] This is also clearly explained in the registrar’s personal information charter:

Companies House retains all records of companies as long as they’re active. Records of dissolved companies are retained for 20 years, before they’re transferred to the Public Records Office at The National Archives (TNA). This includes all information relating to company directors or its officers. [83]

Legislative placement

Primary legislation should establish a central register and specify the authority responsible for creating, maintaining, and operating this register, including how long records should be kept. This should also place responsibilities on the authority to collect, collate, and store the information as structured and standardised data, without prescribing a specific format. Further details can be included in secondary legislation.

Verifying beneficial ownership information for accuracy

Verification is the combination of checks and processes that helps ensure that BOI is accurate and complete at a given point in time. Whilst the primary legal responsibility to ensure information is accurate lies on those reporting the information – who should be required to attest to its accuracy – the information should also be checked for accuracy. Checks can be conducted at different stages in the disclosure process with the aim of ensuring information is of high quality and reliable, maximising its utility and impact. Verifying the identity of beneficial owners and the means through which they hold beneficial ownership is a specific requirement of the FATF Recommendations. [84] There are many different approaches to verification, and there is no one-size-fits-all solution. [85] It is important to bear in mind that all of the components in this guide contribute to information being accurate, not just verification.

Mandate, obligation, and powers

Generally, primary legislation will not detail specific mechanisms for verification, but it should create an obligation for the responsible authority to ensure the accuracy of the information they collect and provide them with the mandate and sufficient powers to do so. Particularly for corporate registrars, historical mandates may prevent them from changing or removing information. Other relevant powers can include powers to require specific information, query information, and data sharing and processing powers. It is important that the legislation includes the powers and mandate to ensure the accuracy of the information.

Box 11. Country examples: Argentina, Ghana, Indonesia, Namibia, and the Philippines

Section 33(2) of Namibia’s Trust Administration Act states that “the [registrar] may take such necessary steps as prescribed to verify the information contained in the register referred to in subsection (1) to guarantee the accuracy of information in such register” (emphasis added). [86] The word “may” gives a mandate to the registrar, but does not place an obligation on it to ensure the accuracy of all information.

In Indonesia, the registrar has the powers to add more beneficial owners in addition to those identified by the company, based on results of audits; information from government or private institutions and professions that manage the data; and other reliable information. [87]

The Philippines has more extensive provisions on verification and includes a non-exhaustive list of ways the responsible authority can verify BOI – including specific checks such as onsite visits – and provides it with the powers to do so. Section 9 of the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) Memorandum Circular No. 15 states:

The Commission may, at any reasonable time, verify the beneficial ownership […] through an on-site inspection of the books and records of the corporation and/or through other means available which may include but not limited to information that may be obtained from other sources such as the books and records of other corporate entities and data gathered by law enforcement and other government agency and/or the Anti-Money Laundering Council (AMLC) in the exercise of their respective functions [emphasis added]. [88]

Also see the examples of Argentina and Ghana in the section above.

Third parties and discrepancy reporting

Verification may involve third parties. For example, AML-regulated entities such as financial institutions or notaries may be required to report discrepancies between the outcomes of their KYC/CDD processes and information held on a central register. [89] In other jurisdictions, information may only be submitted to registrars by certain third parties who are also made responsible for conducting verification checks. Lawmakers should ensure suitable obligations, oversight, and access to facilitate third-party checks are in place, and that no existing legislation could prevent the reporting parties from doing so (e.g. lawyer/client confidentiality). For discrepancy reporting to be most effective, the definitions for BO disclosure and for KYC/CDD should be harmonised, and they should apply to the same corporate vehicle types. Discrepancy reporting can be used as a complementary measure to enhance the quality and accuracy of BOI. The FATF does not allow jurisdictions to solely rely on this approach for verification.

Registrars should have sufficient powers to be able to act on discrepancy reports – for example, to request additional information from the reporting company – to challenge, change, and remove information. A discrepancy reporting mechanism should be supported by clear guidance. This should cover when and how to submit discrepancies, and outline the process for reviewing and resolving discrepancy reports.

Discrepancy reports may contain personal data. Countries should take into account client confidentiality and other relevant issues to ensure discrepancy reporting mechanisms are not unduly inhibited. Relevant privacy and data protection laws should be considered and appropriate data security safeguards should be put in place. Requirements related to discrepancy reporting are likely part of AML legislation, and outside the scope of this guide.

Box 12. Country examples: Slovakia and the United Kingdom

Both Slovakia and the UK use third parties for verification. [90] In the UK, primary legislation for the ROE – the ECTEA – includes a requirement to create provisions for ensuring the accuracy of information in secondary legislation, and provides some further parameters:

(1) The Secretary of State must by regulations make provision requiring the verification of information before an overseas entity—

(a) makes an application under section 4 for registration;

(b) complies with the updating duty under section 7;

(c) makes an application under section 9 for removal.

(2) Regulations under this section may, among other things, make provision—

(a) about the information that must be verified;

(b) about the person by whom the information must be verified;

(c) requiring a statement, evidence or other information to be delivered to the registrar for the purposes of sections 4(1)(c), 7(1)(d) and 9(1) (e).

(3) The first regulations under this section must be made so as to come into force before any applications may be made under section 4(1). [91]

The Register of Overseas Entities (Verification and Provision of Information) Regulations 2022 provide further details on how verification is to be conducted by “regulated persons” under AML legislation (i.e. obliged entities), including specifying the time period for verification, which information should be verified, and defining what verification means

6. — (1) An overseas entity may only undertake a relevant activity after a regulated person has verified the relevant information.

(2) Where a relevant person verifies information under paragraph (1), the verification is valid for the period of three months beginning with the day on which the relevant person verifies the information.

(3) Where a relevant person—

(a) has verified relevant information on behalf of an overseas entity; and

(b) delivers the relevant information to the registrar themselves, they must deliver the statement referred to in paragraph (5) at the same time.

(4) Where a relevant person—

(a) has verified relevant information on behalf of an overseas entity; and

(b) does not deliver that relevant information to the registrar themselves, they must deliver the statement referred to in paragraph (5) to the registrar within 14 days of that information being delivered to the registrar.

(5) The statement is a statement to the registrar providing—

(a) confirmation that—

(i) the relevant person has undertaken the verification of the relevant information; and

(ii) that verification has complied with the requirements of these Regulations and the ECTEA;

(b) the date on which the verification was undertaken;

(c) the names of the registrable beneficial owners, and as the case may be, the managing officers whose identity has been verified, but where it has not been possible to obtain full names, so much of that information as it has been possible to obtain;

(d) the relevant person’s service address;

(e) the relevant person’s email address;

(f) the name of the relevant person’s supervisory authority;

(g) where available, the relevant person’s registration number, or a copy of the certification details, given to the relevant person by their supervisory authority; and

(h) the name of the individual with overall responsibility for identity checks, where that is different to the name of the relevant person.

(6) For the purposes of this regulation—

[…]

(b) subject to sub-paragraph (ba), “verify” means verify on the basis of documents or information in either case obtained from a reliable source which is independent of the person whose identity is being verified, and “verified” and “verification” are to be interpreted accordingly;

(ba) a relevant person may verify the following on the basis of documents or information in either case obtained from a reliable source which is not independent of the person whose identity is being verified—

(i) which of the conditions in paragraph 6 of Schedule 2 to the ECTEA is met in relation to a registrable beneficial owner;

(ii) the required information in paragraphs 3(1)(d) and 5(1)(f) of Schedule 1 to the ECTEA;

(c) documents issued or made available by an official body are to be regarded as being independent of a person even if they are provided or made available to the relevant person by or on behalf of that person [emphasis added]. [92]

The regulations also specify that the regulated person conducting the verification cannot be a family member or known associate. The government has separately published guidance on how to conduct verification, including an annex with examples of documents and information which can be considered from “a reliable source which is independent of the person whose identity is being verified”. [93]

The AML regulations also place a requirement on obliged entities to check the outcome of their KYC/ CDD investigations with the information held by the registrar, and to report any “material discrepancies” to the registrar. [94] This is also accompanied by guidance. [95] Whilst these legislative provisions are robust, there are still weaknesses in the approach to verification, as those verifying statements are not required to submit supporting evidence (i.e. the documents used to verify the information) or an explanation of how the information was verified, which assurances were sought to consider the information “verified”, and which documents were used to do so. [96]

Other provisions

Additionally, countries may include requirements for the registrar to iteratively improve on its approaches to verification in legislation. Irrespective of the approaches taken, the onus of submitting accurate and complete information should be on those reporting the information. Some countries have taken the approach of reversing the burden of proving the accuracy of information by placing it on the reporting parties. This can disincentivise reporting parties from providing inaccurate information, as they could be required to prove its accuracy. This helps foster a culture of compliance among reporting parties, and it can strengthen the integrity of the information in a central register.

Box 13. Country examples: Indonesia, Malaysia, Nigeria, and Slovakia

Nigeria’s 2022 Persons with Significant Control (PSC) Regulations provide robust provisions for verification. Regulation 11 states:

(1) The [Corporate Affairs] Commission shall put measures in place to ensure the accuracy and timeliness of [PSC] information held in the central register, which shall include the processes of –

(a) ensuring timeliness and completeness of all required PSC data collected;

(b) minimising data entry errors; and

(c) learning from the operation of the PSC register and ensuring ongoing improvement of

(i) data collection process, and

(ii) the accuracy of data in the central register

(2) A reporting company or limited liability company shall ensure that the information submitted to the Commission on PSC is accurate and complete.

(3) Notwithstanding the provisions of sub-regulation (1) of this regulation, the burden of proving the accuracy of the PSC information submitted to the Commission shall rest on the reporting company or limited liability partnership. [97]

There is a clear obligation for the registrar to establish mechanisms to improve the accuracy of the information it collects. This also places an obligation on the registrar to take an iterative approach to ensuring information accuracy. The regulations also place the primary responsibility of ensuring the information is accurate on those submitting information.

Slovakia also reverses the burden of proof, and has set up a special procedure for dealing with complaints of inaccurate information. Law no. 315/2016 on the register of public sector partners and on amendments to certain laws states:

(1) The registering body can verify on its own initiative or on the basis of a qualified initiative […] the truthfulness and completeness of the data on the [beneficial owner] entered in the register; the legal status and factual circumstances at the time of initiation of the procedure are decisive for the registering body.

(2) Anyone can file a qualified complaint. A qualified complaint must, in addition to the general filing requirements, contain a description of the facts justifying a reasonable doubt about the truth or completeness of the data on the [beneficial owner] entered in the register. The registering authority does not consider a submission that is not a qualified initiative; [if it does, it] informs the notifier about it.

(3) The registering authority will deliver the decision on the initiation of the procedure to the public sector partner, the authorised person and the notifier of the qualified initiative. In the resolution on the initiation of proceedings, the registering body shall invite the public sector partner to state the facts and propose evidence that confirms the truthfulness and completeness of the entered data, and shall determine the deadline for the authorised person to submit the proposal pursuant to paragraph 4.

(4) The public sector partner is a participant in the proceedings. An authorised person is also a participant in the procedure, if he proposed it within the period determined by the registering authority. The whistleblower of a qualified complaint is not a party to the proceedings, but he has the right to look into the court file, submit documents from which the facts claimed by him emerge, propose evidence and be notified of the date of the hearing.

(5) The registering authority may order a hearing if it deems it necessary.

(6) Public authorities and obliged persons according to special regulation 12 are obliged to cooperate with the registering authority at its request and within the period determined by it in verifying the truthfulness and completeness of the data on the end user of the benefits entered in the register.

(7) If the public sector partner does not reliably prove that the data on the end user of the benefits entered in the register are true and complete, the registering authority will decide on the deletion of the public sector partner from the register; this does not apply if the seriousness of the breach of duty is insignificant in view of the manner of the breach of duty, its consequences, the circumstances under which the duty was breached and the degree of culpability. After the finality of this decision, the public sector partner will be deleted from the register and the procedure for imposing a fine will begin according to § 13 par. 1. Remedies are not admissible against the court’s decision on erasure.

(8) If during the procedure for verifying the truthfulness and completeness of the data on the end user of the benefits entered in the register, the public sector partner is deleted at the proposal of the authorised person, the registering authority will complete this procedure. If the public sector partner does not reliably prove that the data on the end user of the benefits entered in the register were true and complete, the registering authority proceeds according to paragraph 7, with the exception of the decision on deletion. After the finality of the decision according to the previous sentence, the registering authority will start the procedure for imposing a fine according to § 13 par. 1 [emphasis added]. [98]

In both Indonesia and Malaysia, legislation places the burden on companies to conduct specific verification checks prior to submitting the information. In Indonesia, companies are required to check the conformity between the information submitted by the beneficial owner and supporting documents. [99]

Similarly, in Malaysia, the law states:

[I]n ensuring the accuracy of beneficial ownership information, verification of beneficial ownership information at a company’s level must be conducted. A company is obliged to conduct verification of the beneficial ownership information when any of the following situation[s occur]:

(1) When an obligation arises to record the name of a beneficial owner in the register of beneficial owners;

(2) When an obligation arises to record the changes to any particulars of the beneficial ownership information in the register of beneficial owners;

(3) When an obligation arises to register a foreign company under the C[ompanies] A[ct] 2016; or

(4) As and when instructed by the Registrar from time to time. [100]

Legislative placement

Whilst primary legislation should provide a legislative basis for verification and the obligation for the relevant authority to put in place measures to ensure the accuracy and adequacy of BO data, secondary legislation should provide more detailed guidance on what these mechanisms of ensuring data quality are. Where third parties are responsible for verification, governments should produce clear guidance.

Sharing of and access to beneficial ownership information

To maximise the impact of BO reforms, all actors who can use the relevant information to further a country’s policy aims should have access to the information they need. Ideally, the government should have identified potential data users – inside and outside government – in the planning stage and detailed these in supporting policy documents. It should have involved these users in consultations and user research to identify what information they need and in what format. For government data users, this may also need to include systems and data flows mapping. These insights should inform the development and design of a system that meets these needs effectively. The legislation should then contain provisions that will enable the access to and sharing of relevant information for these identified data users. The FATF requires information to be accessible to competent authorities and encourages access for obliged entities. [101] In order for BOI to be effectively used, additional legislation and rules may be required. For example, AML legislation and supervisory rules may require the use of BOI from central registers for KYC/CDD processes, and specify in which circumstances the information can or cannot be relied upon. In addition, procurement legislation may need to change to be able to require and allow procuring entities to use BOI in due diligence and decision-making. These provisions may need to be made very clear and explicit in civil law jurisdictions to enable use. These types of legislative changes are not within the scope of this guidance.

BOI inherently comprises personal information and includes names, dates of birth, contact details, and nationalities. The collection, processing, and access to this information therefore have a bearing on privacy. Privacy and, increasingly, data protection, are human rights that are practically universally recognised and protected by law. Access to BOI should comply with domestic privacy and data protection laws, ensuring a balance between access and safeguarding individuals’ rights to privacy and data protection. How this balance should be struck will be highly context specific. It will be determined by a country’s policy aims, the domestic legal context, and societal norms regarding privacy. Considering privacy and data protection laws when looking at existing legislation in the preliminary phases of the legislative process is crucial (see Considering other legislation above).

Clearly specifying who has access to what

Generally, implementing governments should consider how to safeguard legally protected rights whilst trying to maintain access to sufficient information by relevant user groups that can help achieve stated policy aims. [102] To minimise the interference with the right to privacy, data users should only be provided with the information they require. Generally, this means that a user such as a law enforcement agency will have access to sensitive information such as an individual’s ID numbers, whilst others may not. Different layers of access can be created for different users. For example, competent authorities, financial institutions, journalists, NGOs, and the general public may have varying access levels based on their respective needs and responsibilities. Where information is made available to the public, generally a subset of the data is provided, comprising the minimum number of fields to identify an individual. This often involves removing the individual’s date of birth and residential address to lower the risk of identity theft. Other sensitive fields such as an individual’s sex are often published unnecessarily. [103] It is important to exhaustively specify in legislation which fields will be made available to which user groups, based on user needs. Governments should carefully consider and design access provisions, as well as conduct an assessment of the potential privacy impact of their intended measures. As previously discussed, legislation will be more likely to withstand legal challenges if the purpose of access to information is to achieve broad public interest aims. Any access to information should be necessary to achieving the stated aims, and the infringement on the right to privacy proportional to achieving those aims.

Box 14. Country examples: Armenia, European Union member states, Kenya, Namibia, and the Philippines

Laws should clearly state what information will be made available to whom. Although the Philippines does not have a digital central BO register, the SEC does collect BOI. The legislation clearly states which parties it will and will not be made available to. Section 1 of the SEC’s Circular No. 10 on Beneficial Ownership provides a list of information that is supposed to be submitted by all SEC registered corporations. This includes the name, residential address, nationality, and percentage of ownership interest. It also states that:

Such information, however, shall not be uploaded to the [Securities and Exchange] Commission’s publicly accessible electronic database. Said information shall, nonetheless be made accessible or available in a timely manner to competent authorities for law enforcement and other lawful purposes. [104]

Namibia’s Companies Act, Section 6 states:

The information of the beneficial owner and other information regarding a company held by the Registrar are public information and upon request must be made available by the Registrar for inspection by a member of the public, whether electronically or physically, but the information of the beneficial owner is limited to the full name of the beneficial owner and the nature and extent of beneficial ownership [emphasis added]. [105]

Armenia has a central register which is freely accessible to the public. Article 61 of Armenia’s BO law clearly spells out which information is made available, and that this should be accessible for free:

The following information of the unified state register on legal entities, individual entrepreneurs and state bodies is available from the agency’s official website without paying a state fee through the information system:

1) name, surname or title and organisational legal form;

2) date of registration;

3) registration number;

4) taxpayer’s registration number;

5) enterprise code classifier;

6) location or business address;

7) the name, surname, citizenship of the beneficial owner of the legal entity, the date of becoming the beneficial owner, the grounds for becoming the beneficial owner of the legal entity;

8) information about being in the liquidation process or being deregistered [emphasis added]. [106]

Article 6 also clearly specifies which information is not made publicly available, and makes provisions for the public to access extracts:

1. The information stored in the unified state register is public, except for information about individuals’ passport data, social card number (CSS), their residence and registration addresses and means of communication.

2. Information, as well as extracts from the register, are provided in accordance with the procedure provided by this law [emphasis added]. [107]

Finally, Kenya’s Companies Beneficial Ownership Amendment Regulations indicate clearly which information will be made available and which will not: “The publication or disclosure of the beneficial ownership information under these Regulations shall not include protected personal identifiable information, except where such disclosure is made to a competent authority or pursuant to a court order”. [108]

“Protected personal identifiable information” is defined as including:

(a) birth certificate number, national identity card number or passport number;

(b) personal identification number;

(c) date of birth;

(d) residential address;

(e) telephone number; and

(f) email address […] [109]

The EU’s 2018 fifth anti-money laundering directive (AMLD5), included the following clause:

5. Member States shall ensure that the information on the beneficial ownership is accessible in all cases to:

(a) competent authorities and FIUs, without any restriction;

(b) obliged entities, within the framework of customer due diligence in accordance with Chapter II;

(c) any member of the general public.

The persons referred to in point (c) shall be permitted to access at least the name, the month and year of birth and the country of residence and nationality of the beneficial owner as well as the nature and extent of the beneficial interest held.

Member States may, under conditions to be determined in national law, provide for access to additional information enabling the identification of the beneficial owner. That additional information shall include at least the date of birth or contact details in accordance with data protection rules [emphasis added]. [110]

In November 2022, the Court of Justice of the European Union ruled that the AMLD5 provision making BOI accessible to the public was legally invalid. Part of the reason, as stated in paragraph 82 of the judgement, was because it did not exhaustively specify which information should be made available:

However, it is apparent from the use of the expression “at least” that those provisions allow for data to be made available to the public which are not sufficiently defined and identifiable. Consequently, the substantive rules governing interference with the rights guaranteed in Articles 7 and 8 of the [EU] Charter [of Fundamental Rights] do not meet the requirement of clarity and precision recalled in paragraph 65 above [emphasis added]. [111]

Paragraph 65 details that the provision does not meet the proportionality requirement: