Legislating for effective beneficial ownership transparency reforms in the extractive sector

Components of effective legislation

Policy objectives and purpose of the legislation

The objective of a bill is its backbone, and it should be identified clearly at the beginning of proposed legislation. Subsequent provisions should be consistent with these policy objectives, and they should be necessary and appropriate to achieving those aims.

The policy details should be clear prior to drafting legislation. They should be set out in policy papers and impact assessments, and consultations with government departments, especially those that are potential users of the data, such as mining or extractive licensing agencies; the private sector, including those operating in the extractive sector; any additional users of the data, such as civil society organisations (CSOs) and non-governmental organisations (NGOs); and the general public. [12]

Consultations can help consider the range of possible policy objectives and define and broaden the goals for BO transparency reforms. Once legal provisions are being proposed, drafted and debated, broad consultations with experts, civil society and other stakeholders remain key.

Governments should identify all relevant objectives and specify these in law. The implementation of a BO register may face legal challenges, especially where access to personal data is provided to a broad range of users beyond government to maximise the impact of the reforms. In these instances, courts will look at whether the measures are necessary and proportionate to achieving the stated objectives. Ideally, these should be anchored in broad terms in the public interest, while covering specific obligations such as those in the EITI Standard, the FATF Recommendations, and the UNCAC. Broadly, these can include providing transparency, accountability and oversight to the general public, e.g. over natural resources (see Box 2) or public spending; deterring and tackling illicit activities, including corruption, money laundering and terrorist financing; and facilitating economic growth, e.g. by improving the business environment and enabling the proper functioning of corporate vehicles; among others.

Box 2. Ensuring transparency and tackling corruption in the extractive sector

In numerous countries, extractives have been identified as a high-risk sector for corruption. Consequently, many countries have passed sector-specific legislation incorporating requirements regarding the beneficial ownership of companies engaged in activities within this industry. With the increased adoption of central BO registers focusing on all sectors, a growing number of countries are pursuing transparency in extractives. However, these countries might incorporate more stringent requirements for the extractive sector, or allow broader access to this information.

Beyond the policy objective of tackling corruption within high-risk sectors, there is an overarching case for transparency in extractives, distinct from other industries. This revolves around the recognition embedded in many constitutions that deems citizens as the ultimate owners of natural resources. This underscores the need to reflect these constitutional principles within the legislative framework.

By incorporating these elements, countries can improve the efficacy of their legislative frameworks. This ensures that these frameworks are finely tuned to address the unique challenges and considerations prevalent within the extractive industry, thereby fostering a more robust and accountable governance structure.

Checklist

The legislative framework:

- Includes a clear policy objective at its beginning, anchored broadly in transparency and the public interest

- Has been widely consulted with relevant parties, including but not limited to:

- Ministries responsible for extractives

- Licensing agencies

- Companies in the extractive sector

- EITI national secretariats

- NGOs and CSOs

- Other relevant stakeholders

- Is supported by policy documentation and impact assessments, which have also been widely consulted on with relevant parties

Defining the beneficial ownership of corporate vehicles in law

Building a legislative framework for BO transparency starts with clearly and unambiguously defining beneficial ownership. The definition should cover all aspects of what constitutes a beneficial owner, and it should clearly prescribe low thresholds to ensure that all relevant ownership and control interests are covered. The 2023 EITI Standard includes minimum requirements for the legal definition of beneficial ownership under 2.5(f)(i), in line with other international standards. [13]

The prescription of thresholds is particularly relevant to the extractive sector. The EITI Standard requires countries to “include ownership threshold(s), which should be informed by the country context and the type and level of risk that the country aims to address”. [14] It encourages countries to “adopt an ownership threshold of 10% or lower for beneficial ownership reporting”, as well as “request full disclosure of [PEPs’] beneficial ownership regardless of their level of ownership” for the extractive sector. [15]

The definition should cover the full range of ways a natural person can exercise ownership or control over, or benefit from, a corporate vehicle. Legislation should be complemented by guidance on how to calculate ultimate ownership where such ownership is indirectly held.

As legislation may already contain a definition of beneficial ownership, new legislation should create a single, unified definition. [16] This could be done by expressly adopting, consolidating or amending definitions in existing legislation. Ideally, a broad definition will be contained in primary legislation, with additional secondary legislation referring to this definition and specifying what the definition means when applied to certain corporate vehicles, such as companies or legal arrangements, including providing specific thresholds. This approach can also be applied to sector-specific requirements, such as lower thresholds for the extractive sector. [17] This is to ensure coherence across legislation, and enable compliance and potential additional verification mechanisms, like discrepancy reporting, to function effectively.

Often, a definition will also refer to the corporate vehicles to which it will apply. Defining which criteria constitute beneficial ownership will also determine whether a specific corporate vehicle can be beneficially owned. For a BO disclosure regime to be comprehensive, definitions should consider all forms of ownership and control in an economy, and all corporate vehicles with or without distinct legal personalities through or by which assets can be owned, benefitted from and controlled. These corporate vehicles should be required to make declarations about their beneficial ownership. According to the 2023 EITI Standard 2.5(c), this should include at the very minimum “corporate entity(ies) that apply for or hold a participating interest in an exploration or production oil, gas or mining license or contract”. [18] License applicants or holders should not necessarily be limited solely to entities registered within the country. International best practice recommends broadening the scope to encompass subsidiaries of license holders, as well as intermediaries and subcontractors associated with these corporate entities engaged in activities within the extractive sector.

While some types of corporate vehicles, such as listed companies, may be exempt from the full disclosure requirements, excluding certain corporate vehicles from any type of disclosure can create loopholes. Corporate vehicles exempt from disclosing their beneficial ownership should still be required to make declarations, including the basis for their exemption. Although SOEs and listed companies are often exempted, the EITI Standard includes specific disclosure requirements for both, covered later in this guidance. [19] Any exemptions from full declaration requirements should be clearly defined and justified, made public and reassessed on an ongoing basis. Therefore, they are best placed in secondary legislation. Exemptions from disclosing beneficial ownership may be granted when a corporate vehicle is already disclosing sufficient information and this information is accessible through alternative mechanisms. For example, a listed company may be subject to sufficient disclosure and transparency requirements to a stock exchange or a regulator. SOEs often do not meet these criteria, yet are exempted by many countries. This is particularly relevant for the extractive sector, as many of the corporate vehicles will be listed or have some state ownership. Any exemptions should mention specific criteria (e.g. a list of stock exchanges or jurisdictions) rather than constitute blanket categories. [20] All exemptions should be interpreted narrowly.

Checklist

The legislative framework:

- States that a beneficial owner should be a natural person

- Covers all relevant forms of ownership, control and deriving substantial benefit from

- Specifies that these interests can be held both directly and indirectly

- Includes a single, unified, catch-all definition of what constitutes beneficial ownership, ideally in primary legislation

- Includes a non-exhaustive list of example ways in which beneficial ownership can be held, ideally in secondary legislation

- Specifies a threshold for relevant corporate vehicles, or multiple thresholds based on risk, which is justified in policy documentation, with a threshold of 10% or lower for the extractive sector (or for all sectors)

- Includes a clear prohibition of agents, custodians, employees, intermediaries or nominees acting on behalf of another person qualifying as a beneficial owner

- Specifies that the criteria for beneficial ownership can be met through joint action, and when joint action is assumed

- Defines additional concepts, such as significant control or substantial benefit, as required

- Applies to all corporate vehicles through or by which assets can be owned, benefitted from and controlled, unless exempt

- Exemptions are clear and justified, and this information is made public

- Exempt corporate vehicles are still required to submit declarations

- Is accompanied by guidance to help declarants understand the definition

Reporting obligations

Legislation should clearly specify upon whom reporting obligations fall. Usually, this falls on the corporate vehicle itself. Under international AML standards, companies are also required to hold and maintain their own registers. Therefore, there may also be obligations on the beneficial owner to provide information to the company, and powers for the company to compel the beneficial owners to provide information on request and issue penalties for failures to comply.

The legislation should make the provisions of BO information one of the requirements for incorporating a corporate vehicle. For existing corporate vehicles, the legislation should specify which events trigger reporting. Following an initial requirement for existing corporate vehicles to declare their BO information after the introduction of new legislation, these should include incorporation or formation; any and every subsequent changes to BO information; and annual statutory reporting (e.g. annual returns). Information should be required to be updated within a short, defined time period after these events. To close a loophole explained in Figure 1, all changes in beneficial ownership should be legally required to be reported.

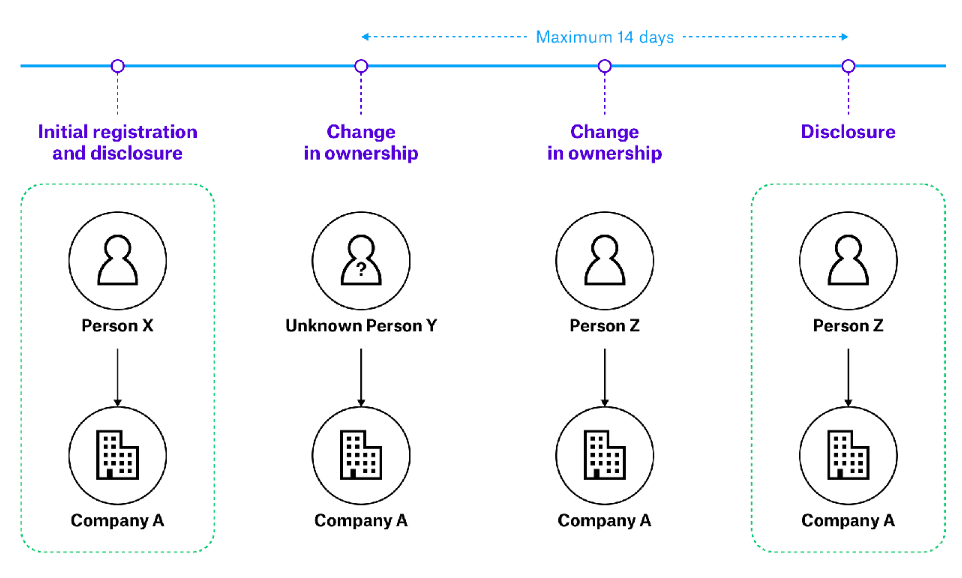

Figure 1. Reporting requirements loophole for changes in beneficial ownership

In this example, Company A has disclosed Person X to be its beneficial owner at initial registration. Later, Person Y replaces Person X as the company’s beneficial owner. The prescribed time period for reporting changes in this jurisdiction is 14 days. Within this time period, the beneficial owner of Company A changes again, from Person Y to Person Z. If there is no requirement to report all changes in beneficial ownership, Person Y can legally avoid disclosure – and potentially exploit this for illicit purposes – provided that Person Z is disclosed as the beneficial owner within the prescribed time period of the first change in ownership. Source: Open Ownership [21]

Legislation should specify clearly what information should be included in a declaration. This should generally comprise information about the beneficial owner; the corporate vehicle; the relationship between them; and the individual submitting the information. Sufficient information should be collected to be able to identify the individuals and corporate vehicles, and to allow the information to be verified. The 2023 EITI Standard includes minimum requirements for information to be made available, with specific requirements for all corporate vehicles (2.5(d) and (g)), PLCs (2.5(f)(iii)), joint ventures (2.5(f)(iv)) and SOEs (2.5(f)(v)). [22] For example, all corporate vehicles are required to disclose whether their beneficial owner is a PEP, as well as their legal owners and shareholders. PLCs and wholly owned subsidiaries are required to disclose the name of the stock exchange and include a link to the stock exchange filings where they are listed to facilitate public access to information on their beneficial owners. SOEs are required to disclose the name of the states owning or controlling the SOE; the level of ownership; and details about how ownership or control is exerted. For more information, see Box 1.

Governments should either collect this information through BO disclosures or collect sufficient information to connect disclosures to this information. For example, if a government has a PEP register, sufficient information should be collected to identify individuals disclosed in the register of PEPs.

Information required to be disclosed should be clearly enumerated in law and limited to what is necessary, in line with common requirements in privacy and data protection legislation. Information should be collected, ideally through online forms with accompanying guidance. It is not considered good practice to include the specific disclosure forms in legislation, as these may need to be amended.

In some countries, extractive regulators may be legally required to collect BO information from companies they regulate, or as part of licensing or permit applications, in addition to the information being centrally collected. As the EITI Standard mandates the disclosure of BO information for those applying for, holding or transferring licenses, even without an enabling legal framework, the EITI process includes the requirement to collect BO information from companies operating in the sector through EITI reporting. It is imperative that forms used for collecting BO information either by the EITI process or extractive regulators are modelled after existing disclosure forms and processes of the authority primarily responsible for collecting BO information. [23] This is important in ensuring uniformity in the data fields collected. Ideally, this information should be checked against and consolidated with any existing information held in order to avoid a situation where a government may hold conflicting information on the beneficial ownership of a single corporate vehicle. Alternatively, these corporate vehicles can be required to confirm the information held by the registrar is correct, and to include an extract from the register.

Checklist

The legislative framework:

- Clearly states which events should trigger a disclosure, including:

- Initial declaration within a specified time from when the obligation in law is created

- Every subsequent new registration or incorporation

- Any and every change to beneficial ownership

- Annual reporting

- Clearly enumerates which information should be collected about the individual; the corporate vehicle; and the relationship between them, and:

- This is sufficient information to either include or identify information required to be disclosed by the EITI Standard 2.5(d), (f) and (g) [24]

- Does not include more information than is considered strictly necessary to achieve the stated objectives

- Includes provisions for this information to be collected in online forms – or analog forms which are subsequently digitised – without copies of these forms being included in legislation

- Is accompanied by guidance to help declarants understand their obligations

The registrar and the register

Legislation should clearly identify the authority to which information should be submitted, and delegate the powers, mandate and responsibility to this authority to create and oversee a register. If part of country-wide BO transparency efforts, these authorities are often corporate registrars, tax authorities or financial investigative units. Sometimes, different authorities oversee registers for different corporate vehicles, for example, legal arrangements such as trusts, or non-profit organisations. In this event, the law should enable sufficient cooperation and exchange of information.

The laws should specify how and for how long records should be kept, which should be a reasonable and specified number of years, including for dormant and dissolved corporate vehicles. To ensure BO information is useful, it should be collected, stored and shared as structured and interoperable data. Primary legislation does not need to specify this in detail, but could place a responsibility on the registrar to ensure information is stored digitally in an organised, accessible and usable way. It is important that legislators do not accidentally design digital systems through legislation, for example, by including disclosure forms in legislation, or including language that is overly specific or not technology neutral.

Where other authorities – e.g. industry regulators, license issuers or a national EITI secretariat – are also mandated to collect BO information, ideally this information should be interoperable and consolidated with the central register.

Checklist

The legislative framework:

- Establishes a register

- Designates a registrar, i.e. an authority in charge of overseeing the register

- Includes the necessary powers, mandate and responsibilities for this authority to collect information, and to administer and maintain the register, including a clear legal basis for collecting and processing information in line with existing privacy and data protection legislation

- Specifies how long information should be kept for

- Enables the collection, storage and sharing of information in a digital and structured format

- Does not prescribe or place limits on the design of those systems

Verifying beneficial ownership information for accuracy

In order for BO information to be useful and usable, governments should put in place mechanisms to verify its accuracy. Information is accurate when it reflects reality at the point of submission: for example, that the beneficial owner is who they say they are, and that that person is actually the beneficial owner. Inaccuracies may be due to accidental errors or omissions, or deliberate falsehoods.

Verifying the identity of the beneficial owners and the means through which ownership or control is exercised in a corporate vehicle is a specific requirement of the FATF Recommendations. [25] Additionally, the EITI Standard’s Requirement 2.5(e) mandates multi-stakeholder groups to “assess any existing mechanisms for assuring the reliability of beneficial ownership information and agree [on] an approach [...] to assure the accuracy of the beneficial ownership information they provide”, while 2.5(c) requires that BO information must include the “identity(ies) of their beneficial owner(s); the level of ownership; and details about how ownership or control is exerted”. [26] Additionally, countries are recommended to verify the information provided about the corporate vehicle and the individual making the declaration. There are many different approaches to verification, and there is no one-size-fits-all solution. [27] Generally, primary legislation will not detail specific mechanisms, but should include provisions to require and powers to enable the registrar to ensure accuracy, including the ability to share data with other relevant authorities.

Verification may involve third parties. For example, information may be allowed or required to be submitted, or checked by AML-regulated entities such as financial institutions or notaries through discrepancy reporting. Lawmakers should ensure suitable obligations and oversight are in place, and that no existing legislation could prevent the registrar from doing its job (e.g. lawyer/client confidentiality).

Checklist

The legislative framework:

- Places the responsibility on the registrar to ensure the accuracy of information

- Provides the mandate and powers for the registrar to ensure the accuracy of information, including:

- Powers to require information

- Powers to remove material from the register

- Powers to correct or query information

- Powers to take action against those failing to provide information

- Data sharing and processing powers

- Includes suitable obligations, oversight and sanctions for third-parties involved in BO disclosure

Sharing and accessing beneficial ownership information

To maximise the impact of the reforms, all actors who can use the relevant information to further a country’s policy aims and strengthen citizens’ involvement in corruption mitigation measures should have access to the information when they need it. The legislation should make provisions for the sharing of and access to BO information in line with privacy and data protection requirements. BO information comprises, by definition, personal information, and therefore has a bearing on privacy. Privacy and, increasingly, data protection, are practically universal, legally protected human rights. All access provisions should be legislated for in line with domestic privacy and data protection legislation and obligations, and should seek to balance access to the information with any interference with legally protected rights. This balance will be highly context-specific and should consider policy aims as well as the domestic legal context and norms around privacy in society. Where these aims are anchored broadly in the public interest, the potential benefit of broader access to information should be carefully weighed against private interests. Generally, implementing governments should consider how to safeguard legally protected rights as much as possible while trying to preserve the usefulness and usability of the information.

Ideally, the government will have identified potential data users inside and outside government in supporting policy documents, and included them in both consultations and user research as part of developing and designing a system. Consultations and user research should also inform the information that various users need, and its format. To minimise the interference with the right to privacy, data users should only be provided with the information they require. Generally, this means that a user such as law enforcement will have access to sensitive information such as ID numbers, while others may not. Different layers of access can be created for different users. Where possible and justified, the easiest way to meet the information needs of the widest range of relevant data users is by making it publicly available.

Where information is made available to the public, generally a subset of the data is provided, comprising the minimum number of fields to identify an individual. This often involves removing the individual’s day of birth to lower the risk of identity theft. Other sensitive fields, such as an individual’s sex or gender, are often published unnecessarily. [28] Governments should carefully consider and design access provisions, and conduct an assessment of the potential impact on privacy of their intended measures. The 2023 EITI Standard includes specific requirements regarding which data fields should be made publicly available, including: the name of the beneficial owner; their nationality; and their country of residence; as well as identifying any PEPs and specific data accessibility requirements under Requirement 7.2. [29] This is considered best practice in mitigating risks in the extractive sector. Where information is made publicly available, making this free to access will maximise its impact. Charging a fee for this information will decrease its use, and may be counterproductive.

This is considered best practice in mitigating risks in the extractive sector. Where information is made publicly available, making this free to access will maximise its impact. Charging a fee for this information will decrease its use, and may be counterproductive.

Generally, personal data should only be used for specified purposes, and the risk to privacy arises from information being misused for different purposes. Various approaches can be taken by governments to prevent and detect misuse. Governments should have already spelled out their policy objectives in the law and various supporting policy documents, as covered above. The EITI Standard’s policy objectives relate to transparency, accountability and oversight. Legislation will be more likely to withstand legal challenges if the purpose of access to information is to achieve these broad public interest aims.

Methods to reduce misuse include providing information to certain users with a legitimate interest, particularly where this concerns access to a large amount of information, and high flexibility in how this information can be searched and used. This can be implemented in addition to, rather than instead of, public access. Other measures can include registration; attestations to use the data in line with specific purposes; and data licenses. While these specific measures are not likely to be included in primary legislation, broad provisions for access may be. Alternatively, legislation may designate certain user groups as having a legitimate interest by default. The EITI Standard places certain requirements on the format and access of EITI data under Requirement 7.2. [30] Countries could consider specific access provisions for the subset of corporate vehicles covered in Requirement 2.5(c) (see Box 3). [31]

In order for BO information to be effectively used, additional legislation and rules may be required. For example, licensing legislation and rules may mandate and require the use of BO information from central registers for specific purposes, and they may need to change to enable the use of BO information in licensing due diligence and decision-making. These types of legislative changes are not within the scope of this guidance.

Box 3. Sharing data across agencies to use beneficial ownership information in licensing

Legislation should enable data sharing across agencies to enable active use of BO information for specific policy objectives. In the case of the extractive sector, two requirements under the 2023 EITI Standard reinforce the connection between licensing and BO information, helping ensure that licenses are granted to transparent and accountable entities.

- Requirement 2.2(c): “Where licenses are awarded through a bidding process, the government is required to disclose the list of applicants, including their beneficial owners in accordance with Requirement 2.5, and the bid criteria”. [32]

- Requirement 2.3(d): “Implementing countries are encouraged to link publicly available license registers to other government platforms that disclose or hold information in accordance with Requirement 2.5 on the legal and beneficial owners of oil, gas and mining companies”. [33]

Linking information can help regulators analyse who is behind the corporate vehicles applying for, holding or transferring licenses.

Checklist

The legislative framework:

- Takes into account the specific requirements about public access to BO information – considered best practice in mitigating risks in the extractive sector – and its format under requirements 2.2, 2.3, 2.5 and 7.2 of the 2023 EITI Standard [34]

- Includes a clear legal basis for sharing and accessing information, clearly stating its purpose

- Where the purpose is broadly anchored in the public interest, such as where ownership of natural resources is involved, consider whether public access is necessary and proportional

- Considers domestic obligations and rights with respect to privacy and data protection under existing legislation

- Makes provisions for access for relevant data users identified in policy documents, which is both necessary and proportional to the stated objectives

- Mitigates interference with legally protected rights to the extent possible

- Makes provisions for a protection regime, including clear criteria so exemptions to access are not discretionary or arbitrary

- Clearly states which data fields are made available to which user groups in a system of layered access, based on the minimum data needed

- Includes additional relevant safeguards commensurate to the access

Sanctions for noncompliance

Finally, the legislation should include sanctions to ensure compliance. These should be effective, proportionate, dissuasive and enforceable. Sanctions should exist for all forms of noncompliance, and they should cover all the persons involved in declarations as well as key persons of the corporate vehicle. Sanctions are not the only way to achieve compliance. Many aspects covered above, e.g. public consultations and education, accessible guidance and easy-to-use forms, can all contribute to higher compliance levels.

Sanctions should include both administrative and criminal sanctions. In order to be effective, financial sanctions should be set sufficiently high. Low financial sanctions can be seen as the cost of doing business and may lead to corporate vehicles opting for noncompliance. Financial sanctions should be complemented by non-financial sanctions, which can be more effective. [35] For example, preventing financial institutions from doing business with corporate vehicles that have not met their reporting requirements is a highly effective approach to ensuring compliance. These can also be specific to the extractive sector. For instance, sanctions could prevent noncompliant individuals or companies from holding extractive licenses.

Primary legislation should contain provisions authorising regulatory agencies to issue administrative sanctions. Details of these sanctions can be set out in secondary legislation.

Checklist

The legislative framework:

- Includes sanctions for all types of noncompliance, including:

- Non-submission

- Late submission

- Incomplete submission

- Incorrect submission, clearly distinguishing this from a deliberately false submission

- Persistent noncompliance

- Other obligations related to BO disclosure (e.g. for third parties)

- Includes sanctions on all parties involved in disclosure, including:

- Beneficial owner(s)

- Declaring person

- Company officers

- The declaring corporate vehicle

- Includes administrative and criminal sanctions

- Includes financial and non-financial sanctions

- Sanctions are sufficiently high to be dissuasive, yet proportional

- Sanctions are enforceable, and automated where possible

- Clearly determines which authority is responsible and authorised to enforce sanctions

- Ensures the registrar has the authority to issue basic administrative sanctions and enforce the collection of information

- Provides sufficient resources, legal mandate and powers to all authorities involved in the sanctions to enforce them

Footnotes

[12] Please see: Thom Townsend, “Introduction” in Effective consultation processes for beneficial ownership transparency reform (s.l.: Open Ownership, 2020), https://www.openownership.org/en/publications/effective-consultation-processes-for-beneficial-ownership-transparency-reform/introduction/.

[13] EITI, The EITI Standard 2023 – Part 1, 20.

[14] EITI, The EITI Standard 2023 – Part 1, 20.

[15] EITI, The EITI Standard 2023 – Part 1, 20.

[16] Most jurisdictions will already have a definition of beneficial ownership in their laws; for example, in their AML legislation or in legislation outlining customer due diligence requirements for financial institutions. See FATF Recommendation 10: FATF, The FATF Recommendations, 14–15, 66–75.

[17] Specific legislation will take precedence over general legislation in most jurisdictions. If primary BO transparency legislation does include thresholds, sector-specific thresholds may also need to be in primary legislation, as secondary legislation cannot prevail over primary legislation.

[18] EITI, The EITI Standard 2023 – Part 1, 20.

[19] EITI, The EITI Standard 2023 – Part 1, 20-21.

[20] The disclosure and transparency requirements of stock exchanges and regulators of listed companies can vary significantly. Therefore, blanket exemptions should not be given to listed companies. Exemptions should be given on the specific transparency and disclosure requirements they are subject to. For more information, see: Ramandeep Kaur Chhina and Tymon Kiepe, Defining and capturing information on the beneficial ownership of listed companies (s.l.: Open Ownership, 2024), https://www.openownership.org/en/publications/defining-and-capturing-information-on-the-beneficial-ownership-of-publicly-listed-companies/.

[21] Ramandeep Kaur Chhina and Tymon Kiepe, Designing sanctions and their enforcement for beneficial ownership disclosure (s.l.: Open Ownership, 2022), 5, https://www.openownership.org/en/publications/designing-sanctions-and-their-enforcement-for-beneficial-ownership-disclosure/.

[22] EITI, The EITI Standard 2023 – Part 1, 20–21.

[23] EITI, EITI Requirement 2.5 – Beneficial ownership model declaration form (Oslo: EITI, 2020), https://eiti.org/guidance-notes/beneficial-ownership-model-declaration-form.

[24] EITI, The EITI Standard 2023 – Part 1, 20–21.

[25] FATF, The FATF Recommendations, 96.

[26] EITI, The EITI Standard 2023 – Part 1, 20.

[27] For more information, see: Tymon Kiepe, Verification of beneficial ownership data (s.l.: Open Ownership, 2020), https://www.openownership.org/en/publications/verification-of-beneficial-ownership-data/.

[28] Lubumbe Van de Velde, Gender and beneficial ownership transparency (s.l.: Open Ownership, 2022), https://www.openownership.org/en/publications/gender-and-beneficial-ownership-transparency/.

[29] EITI, The EITI Standard 2023 – Part 1, 37.

[30] EITI, The EITI Standard 2023 – Part 1, 37.

[31] EITI, The EITI Standard 2023 – Part 1, 20, 37.

[32] EITI, The EITI Standard 2023 – Part 1, 16.

[33] EITI, The EITI Standard 2023 – Part 1, 17.

[34] EITI, The EITI Standard 2023 – Part 1, 15–16, 17, 19–21, 37.

[35] Chhina and Kiepe, Designing sanctions and their enforcement for beneficial ownership disclosure.