Leveraging ownership information to improve taxation

Domestic and international frameworks relating to beneficial ownership information for taxation

The use cases discussed above all require BO information about both domestic and non-domestic legal vehicles. The key relevant international regulatory frameworks relating to the collection and exchange of BO information for legal vehicles are the FATF’s Recommendations and the OECD’s international tax transparency standards. The FATF Recommendations cover the collection of BO information of legal vehicles by central government registers and certain regulated entities as part of a broader framework for countries to combat money laundering, terrorist financing, and financing the proliferation of weapons of mass destruction. [77] Over 200 jurisdictions around the world have committed to the FATF Recommendations through the FATF membership or membership of so-called FATF-style regional bodies. [78]

The OECD’s tax transparency standards consist of the standard for Exchange of Information on Request (EOIR) adopted in 2009 and the AEOI, comprising the Common Reporting Standard (CRS) adopted in 2014, and the more recently adopted Crypto-Asset Reporting Framework. The AEOI and EOIR standards aim to combat tax evasion perpetrated through holding undeclared assets by enabling jurisdictions to reciprocally share information they hold about each other’s tax residents. The AEOI is modelled on and a response to the US’s Foreign Accounts Tax Compliance Act from 2010.

The OECD has adopted the FATF’s definition of BO for the EOIR and the AEOI standards. The implementation of both FATF’s Recommendations and the OECD’s tax transparency standards is assessed by periodic peer reviews. The implementation reviews of the tax transparency standards are organised by the Global Forum on Tax Transparency and Exchange of Information for Tax Purposes. As of January 2025, the Global Forum has 171 members, although members are in different stages and have different timelines for implementing these mechanisms. [79]

Central beneficial ownership registers and exchange of information on request

To meet the requirements of the FATF’s 2022 and 2023 revisions relating to BOT for legal entities (Recommendation 24) and legal arrangements (Recommendation 25), most countries require legal entities – and, albeit to a lesser extent, legal arrangements – to disclose their BO to a central register. [80] These registers are often maintained by a company registrar, or otherwise by other agencies, including by tax authorities, as is predominantly the case in Latin America. [81] In the UK, the company registrar collects BO information for all legal entities, while the tax authority collects BO information for certain trusts, initially restricted to those which had a tax implication but subsequently expanded. Tax authorities variably hold information about legal arrangements and the assets they hold.

Some countries have implemented central BO registers for broader purposes, including enabling the functioning of legal entities and preventing their misuse more generally (e.g. Latvia and the UK), enabling the use of the information for multiple purposes. Some countries specifically list tax and tax integrity as policy objectives (e.g. Australia, Brazil, and Peru). [82] Typically, these central registers include BO information for domestic legal vehicles. [83] The policy objectives set by the jurisdiction generally determine – and potentially limit – how the information can be accessed and used, and by whom.

Central BO registers are also a key aspect of the EOIR. The EOIR standard includes the “identity of the legal and beneficial owners (and the identity of other relevant persons […]) of relevant entities and arrangements” as part of ownership and identity information, along with account and banking information. [84] Many jurisdictions rely on their central BO registers to satisfy the requirements of the EOIR standard. [85] Despite participating in the mechanism, some tax authorities report that it is difficult to get information from some jurisdictions.

While the EOIR standard uses the FATF definition of BO, it also recognises some differences: “regarding beneficial ownership information applicable under [the EOIR], it is recognised that the purposes for which the FATF standards have been developed (combatting money-laundering and terrorist financing) are different from the purpose of the standard on EOIR (ensuring effective exchange of information for tax purposes)”. [86] Not all information collected as part of complying with the FATF Recommendations may be relevant to and shareable under the EOIR.

Financial institutions and the automatic exchange of information

Under Recommendation 10, the FATF requires financial institutions (FIs) and other designated non-financial businesses and professions – collectively called obliged entities – to establish the BO of their customers as part of AML statutory requirements relating to customer due diligence (CDD) and know-your-customer (KYC) checks. [87] As part of verification measures, some jurisdictions may require obliged entities to check their findings against central BO registers and report any discrepancies. [88] Some jurisdictions also allow or require obliged entities to use information from central registers as part of their statutory CDD requirements. [89]

FIs also play a key role in domestic tax administration and tax transparency. In most jurisdictions, tax administrations have the authority to access information that FIs hold on taxpayers to ensure compliance, i.e. that taxpayers are reporting all taxable assets and income as well as paying the right levels of tax. FIs also play a key role in the AEOI. The information standard used by the AEOI – the CRS – includes the term “Controlling Persons”, which is aligned with FATF’s definition of a beneficial owner. [90]

Under the AOEI, FIs are responsible for identifying reportable accounts. Reportable accounts are those for which the account holders or controlling persons are tax residents in a participating jurisdiction. This includes both the entities and the controlling persons when an entity holds an account that is deemed passive, i.e. receiving more than 50% of its earnings as passive income from interest, rents, dividends, and royalties. [91] For information about controlling persons, FIs may rely on information acquired as part of AML obligations. [92]

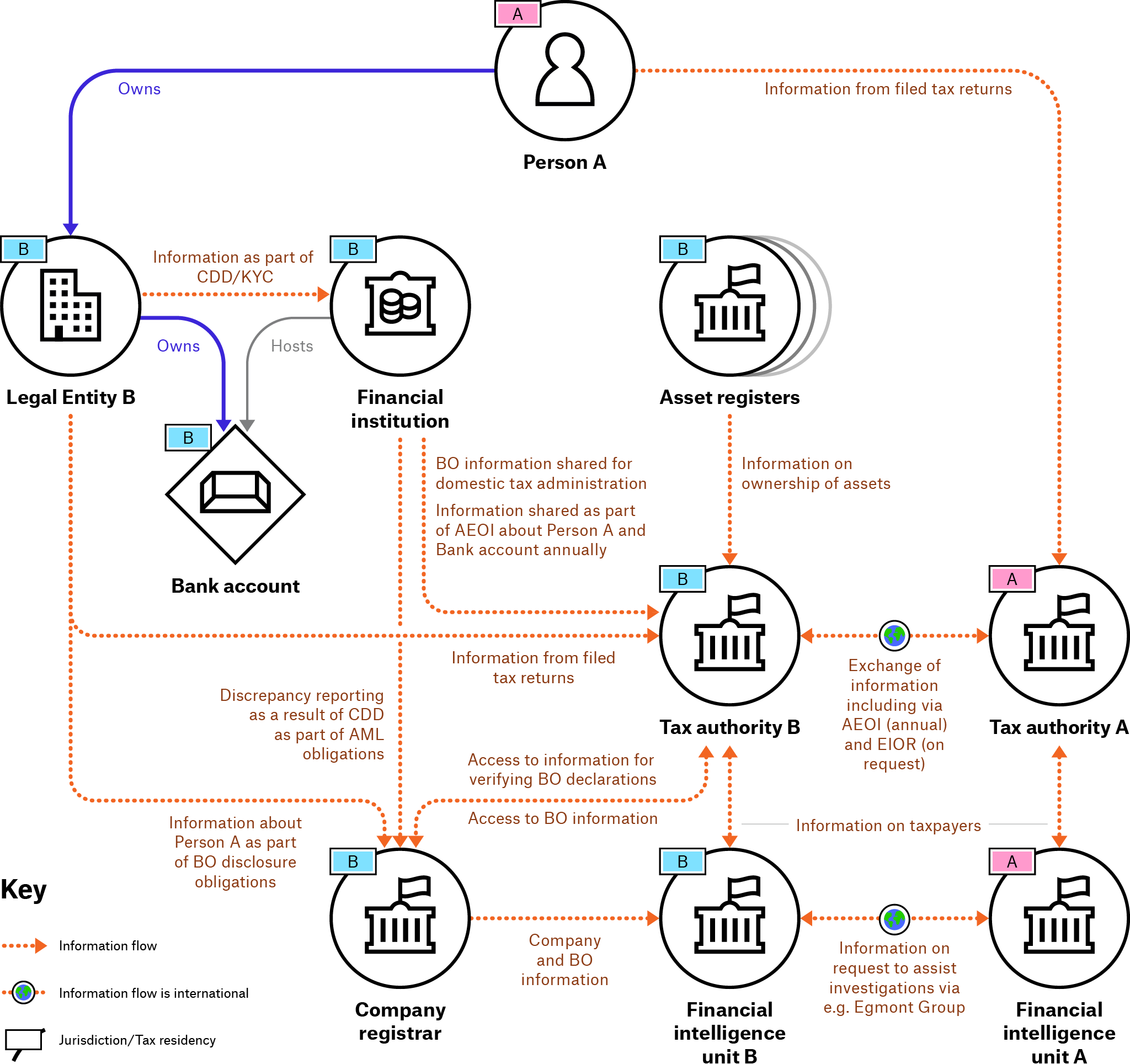

FIs report information to their domestic tax authority annually. [93] Information about any tax residents of participating foreign jurisdictions is then shared with the corresponding tax authority. Participating jurisdictions share information on an annual basis in bulk, which includes information on identities, including tax identification numbers, and information about the account, including a year-end balance or value and distributions made to the account. [94] Figure 2 shows the information flows between different registers, authorities, and jurisdictions, under the frameworks discussed.

Figure 2. Example of domestic and international flows of information about beneficial ownership networks

The diagram shows an example of the multiple avenues through which BO information about legal vehicles can be exchanged and used for taxation, domestically and internationally. In this illustrative example, Legal Entity B is incorporated and tax resident in Jurisdiction A, where the company registrar collects BO information for legal entities. The entity is beneficially owned by a tax resident of Jurisdiction B. The dotted lines represent domestic and international information flows

The AEOI can help increase tax revenues. [95] The extent to which it does this depends on the quality of its implementation, including the degree of digitisation and enforcement, and the capacity of the recipient to use the information. [96] For example, a 2023 report stated an African country collected EUR 10.6 million in additional revenue by using information obtained through the AEOI. [97]

However, issues identified with the AOEI include that the completeness of information and its usability can vary from jurisdiction to jurisdiction. [98] This can be attributed to certain fields – such as dates of birth and tax identification numbers – not being mandatory, the potential duplication of information received, and because the co-ownership of accounts is not identified. [99] The information is only shared annually – at different times by different jurisdictions – and is therefore not readily accessible and up to date. [100] Some of these issues can be resolved through automated processes by the recipient country, which requires either in-house skills and capacity to do so or resources to rely on commercial solutions. The information that is received is reported to be very accurate, partly attributable to the peer-review mechanism. [101] Some tax authorities also use BO information from commercial providers.

Information that FIs hold on BO (and subsequently share through the AEOI) may not be readily comparable to that held by central registers. This can be due to several factors, including differences in legal definitions of BO in laws governing AML obligations for FIs, disclosure requirements for legal vehicles not being aligned within jurisdictions, and approaches to identifying BO not being aligned. However, more jurisdictions are aligning these definitions and including requirements for obliged entities to report any discrepancies between the outcomes of their CDD/KYC processes and information held on central BO registers for legal vehicles, and these different sources of information are slowly converging, although a single view of BO of legal vehicles is still a distant reality.

There may be some overlap between BO information received through the AEOI and the information held by the domestic central BO registers, for example, when a domestic entity has a foreign bank account and it also has beneficial owners that are tax residents in the jurisdiction. However, while this information would pertain to the same entity, BO information is most useful when it is up to date and there is a complete record of changes made over time. [102] As mentioned above, information exchanged through the AEOI would only be updated annually.

Beneficial ownership information for non-financial assets

Most tax authorities have extensive access to domestic registers of assets, such as motor vehicles, land and real estate, as well as vessels. These registers often contain information on the legal ownership of such assets. Assets may be held by a legal entity or a trustee on behalf of another individual or legal entity, and registers often do not contain information on who ultimately owns, enjoys, profits from these assets. At the domestic level, some jurisdictions require the disclosure of the beneficial owners behind entities involved in the transfer of property. In Argentina, for example, notaries involved in the transaction are required to report this to the real estate register. [103] Where legal vehicles are based abroad, this can pose a particular challenge. [104]

There is evidence that international tax transparency measures have led to a reduction in cross-border bank deposits held in tax havens, suggesting that these have been successful in reducing tax evasion through holding undeclared financial assets in foreign bank accounts. [105] Research suggests that the implementation of the CRS may lead to a significant shift in wealth held in financial assets to real estate investments. [106] As a result, there is an increasing focus on transparency in and access to information about the ownership of assets, specifically real estate.

In a 2024 report, the OECD noted that “under existing international legal instruments jurisdictions are generally required to exchange available real estate information upon request for tax purposes”, however, “jurisdictions are not obliged to ensure the availability and access to such information and therefore not all jurisdictions’ tax administrations have ready access to such information. Moreover, the scope of spontaneous and automatic exchanges of information on real estate remains limited at present”. [107]

As a result, the OECD is exploring solutions to ensure the availability of up-to-date BO information on real estate. [108] The EU has already taken steps towards this, requiring member states to set up a single access point to “information which allows for the identification in a timely manner of any real estate property and of the natural persons or legal entities or legal arrangements owning that property” by all domestic competent authorities by 2029. [109] Additionally, the EU requires the registration of the BO of all foreign entities that own real estate with retroactivity until 1 January 2014, similar to the UK’s Register of Overseas Entities (ROE). [110] Information on asset ownership by non-resident entities and offshore asset ownership by residents is key information for tax authorities. To address this, there are also calls for a global asset register for tax purposes, both by civil society and multilateral actors, although it is not clear what shape this would take. [111]

Footnotes

[77] FATF, International Standards on Combating Money Laundering and the Financing of Terrorism & Proliferation – The FATF Recommendations (FATF, updated 2023), https://www.fatf-gafi.org/content/dam/fatf-gafi/recommendations/FATF%20Recommendations%202012.pdf.coredownload.inline.pdf.

[78] “Countries”, FATF, n.d., https://www.fatf-gafi.org/en/countries.html.

[79] “Glossary”, OECD Compare your country – Tax cooperation, n.d., https://www.compareyourcountry.org/tax-cooperation/en/3/all/EOIR_rating_round_1; “Automatic Exchange of Information (AEOI): Status of Commitments”, OECD, Global Forum on Transparency and Exchange of Information for Tax Purposes, updated 13 January 2025, https://web-archive.oecd.org/tax/transparency/documents/aeoi-commitments.pdf.

[80] FATF, The FATF Recommendations, 93–102.

[81] Andres Knobel and Florencia Lorenzo, Beneficial ownership registration around the world 2022 (Tax Justice Network, 2022), https://taxjustice.net/wp-content/uploads/2022/12/State-of-Play-of-Beneficial-Ownership-2022-Tax-Justice-Network.pdf.

[82] Australian Government, The Treasury, Multinational tax integrity; Government of Brazil, “Instrução Normativa RFB nº 2119”, 6 December 2022, http://normas.receita.fazenda.gov.br/sijut2consulta/link.action?idAto=127567; Government of Peru, “RESOLUCIÓN DE SUPERINTENDENCIA N.° 185-2019/SUNAT”, 23 September 2019, https://www.sunat.gob.pe/legislacion/superin/2019/185-2019.pdf.

[83] Some jurisdictions also collect BO information for non-domestic legal vehicles, for example, when these hold specific assets, such as the ROE in the UK.

[84] OECD, Exchange of Information on Request: Handbook for Peer Reviews 2016-2020 – 2016 Terms of Reference, Third Edition (OECD, 2020), 19, https://web-archive.oecd.org/tax/transparency/documents/terms-of-reference.pdf.

[85] See, for example, for Latin America: Rodriguez Pratt, Implementación del beneficiario final en economías en desarrollo, 25–26.

[86] OECD, Exchange of Information of Request, 19.

[87] FATF, The FATF Recommendations, 66–74.

[88] FATF, Guidance on Beneficial Ownership of Legal Persons (FATF, 2023), 25–26, https://www.fatf-gafi.org/content/dam/fatf-gafi/guidance/Guidance-Beneficial-Ownership-Legal-Persons.pdf.coredownload.pdf.

[89] For example, in the Netherlands: Dutch Banking Association, Risk-based industry baseline: UBO identification and verification of the UBO’s identity (Dutch Banking Association, 2023), 5, https://www.nvb.nl/media/5702/nvb-standaarden_1_ubo_30-5.pdf.

[90] OECD, Standard for Automatic Exchange of Financial Account Information in Tax Matters, Second Edition (OECD, 2017), https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264267992-en.

[91] OECD, Standard for Automatic Exchange, Second Edition, 57–58.

[92] OECD, Standard for Automatic Exchange of Financial Account Information – Common Reporting Standard (OECD, 2014), archived 14 May 2014, at the Wayback Machine, https://web.archive.org/web/20140514041621/http://www.oecd.org/ctp/exchange-of-tax-information/automatic-exchange-financial-account-information-common-reporting-standard.pdf.

[93] See, for example: UK Government, HM Revenue & Customs, “Guidance – How to report Automatic Exchange of Information”, updated 23 June 2021, https://www.gov.uk/guidance/how-to-report-automatic-exchange-of-information.

[94] OECD, Standard for Automatic Exchange, Second Edition, 24–25.

[95] Hjalte Fejerskov Boas, Niels Johannesen, Claus Thustrup Kreiner, Lauge Larsen, and Gabriel Zucman, Taxing Capital in a Globalized World: The Effects of Automatic Information Exchange (Saïd Business School, 2024), https://oxfordtax.web.ox.ac.uk/sitefiles/taxing-capital-in-a-globalized-world-the-effects-of-automatic-information-exchange.

[96] Annette Alstadsæter, Elisa Casi, Jakob Miethe, and Barbara Stage, “Lost in Information: National Implementation of Global Tax Agreements”, NHH Dept. of Business and Management Science no. 2023/22 (2023), https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=4630849.

[97] African Union, ATAF, and OECD, Tax Transparency in Africa 2023: Africa Initiative Progress Report (OECD, 2023), 17, https://web-archive.oecd.org/temp/2023-07-21/659894-tax-transparency-in-africa-2023.htm.

[98] OECD, Peer Review of the Automatic Exchange of Financial Account Information 2023 Update (OECD, 2023), 17, https://doi.org/10.1787/5c9f58ae-en.

[99] Reviewer, 27 January 2025.

[100] OECD, Enhancing International Tax Transparency on Real Estate, 24.

[101] Reviewer, 28 January 2025.

[102] Kadie Armstrong, Building an auditable record of beneficial ownership (Open Ownership, 2022), https://www.openownership.org/en/publications/building-an-auditable-record-of-beneficial-ownership/.

[103] Rodriguez Pratt, Implementación del beneficiario final en economías en desarrollo, 23.

[104] See, for example: Government of Norway, Ministry of Finance, “Kartlegging av myndighetenes bruk av opplysninger om eierskap av aksjer og fast eiendom”, 26 January 2024, 3, https://www.regjeringen.no/no/aktuelt/kartlegging-eierskapsopplysninger/id3023024/.

[105] Jeanne Bomare and Ségal Le Guern Herry, Will We Ever Be Able to Track Offshore Wealth? Evidence from the Offshore Real Estate Market in the UK – Working Paper No. 4 (EU Tax Observatory, 2022), https://www.taxobservatory.eu//www-site/uploads/2022/06/BLGH_June2022.pdf.

[106] Bomare and Le Guern Herry, Will We Ever Be Able to Track Offshore Wealth?.

[107] OECD, Strengthening International Tax Transparency on Real Estate – From Concept to Reality.

[108] OECD, Enhancing International Tax Transparency on Real Estate: OECD Report to the G20 Finance Ministers and Central Bank Governors (OECD, 2023), https://www.oecd.org/content/dam/oecd/en/publications/reports/2023/07/enhancing-international-tax-transparency-on-real-estate_4567c0aa/37292361-en.pdf.

[109] Official Journal of the European Union, “Directive (EU) 2024/1640 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 31 May 2024 on the mechanisms to be put in place by Member States for the prevention of the use of the financial system for the purposes of money laundering or terrorist financing, amending Directive (EU) 2019/1937, and amending and repealing Directive (EU) 2015/849”, (AMLD6) Article 18, 31 May 2024, https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/HTML/?uri=OJ:L_202401640&qid=1718774932504.

[110] European Council, Press Release, “Anti-money laundering: Council and Parliament strike deal on stricter rules”, updated 14 February 2024, https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/press/press-releases/2024/01/18/anti-money-laundering-council-and-parliament-strike-deal-on-stricter-rules/.

[111] Independent Commission for the Reform of International Corporate Taxation (ICRICT), It is Time for a Global Asset Registry to Tackle Hidden Wealth (ICRICT, 2022), https://www.icrict.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/04/ICRICTGARreportEN.pdf; DESA, Elements paper for the outcome document, 3.