Leveraging ownership information to improve taxation

Policy considerations

The Open Ownership Principles provide a framework for effective BO disclosure, outlining the elements that influence whether the implementation of BOT reforms can generate high-quality and reliable data, maximising usability. [112] The Principles provide a guiding framework for jurisdictions seeking to implement central BO registers for legal vehicles in order to support effective taxation.

Building on this framework, the following section sets out broad implementation considerations which can make BO information more useful and usable for tax authorities.

A whole-of-government approach

Taking a whole-of-government approach to implementing centralised BO registers for legal vehicles involves creating a single platform for various authorities to access information to meet a range of different policy aims. [113] In many jurisdictions, multiple government agencies collect BO information according to their own definitions. This can have a number of drawbacks. It can lead to a higher compliance burden and confusion for those that need to comply, and it also fails to leverage government-wide resources and registers to verify information. Both of these may lead to lower-quality information. Additionally, a government may hold conflicting information on the same legal vehicle, unable to confirm which one is incorrect, and unable to consolidate the information due to definitional differences.

Governments should work towards a single, accurate view of the ownership and control of legal vehicles. Accuracy of information can be a significant barrier for tax authorities. Tax authorities can both benefit from and significantly contribute to verification mechanisms, as they are likely to hold relevant information that BO declarations can be verified against. [114] A whole-of-government approach can ensure the resources of various government agencies are leveraged to ensure the information is accurate.

Legislating for a whole-of-government approach means anchoring a broad and foundational purpose for the reforms in law. Legislating for ensuring the proper functioning of legal vehicles, their transparency, and preventing their misuse will enable BO information to be used for multiple policy aims. [115] Currently, many jurisdictions are implementing BO registers for legal vehicles for relatively narrow purposes, such as AML. Legislating for these purposes often legally restricts the use of information in other areas, limiting the effectiveness of the register. Even if other users can access the information, if they have not been included in the implementation process to identify and factor in their needs, the information may not be as useful to these parties as it could be. For example, central BO registers may not collect identifiers that allow tax authorities to match individuals and entities to their own information. Where tax authorities are not in charge of the central BO register for legal vehicles themselves, they should be involved from the early stages of BO implementation to ensure their specific needs are met. [116] Conversely, jurisdictions that have only pursued tax objectives through BOT and housed central registers with tax authorities will likely limit the potential to use BO information for other purposes.

All relevant domestic authorities should be given direct access to necessary information based on user research. In a 2024 survey about the use of information on the ownership of shares and real estate, the Norwegian Tax Administration found that “information about ownership is important for the performance of the social missions of many authorities and is used for several different purposes”, including supervision, taxation, national security, local government, and effective administration, and that these all require better access. [117]

In some countries, such as the Philippines, access by the tax authority to BO information from the central register is still conducted manually and on request. It can take weeks or months for a reply, severely limiting its usefulness. Improving the efficiency of this information exchange has been identified as an objective within the Philippines reform plans for 2025. [118] By contrast, Indonesia’s Directorate General of Tax has direct access to the central BO register held by the Ministry of Law.

Where BO information for legal vehicles is made available to users beyond government users, this can enable civil society actors including academics, researchers, and advocacy groups to help contribute to tax integrity. This can include identifying cases of noncompliance and conducting supporting analysis. For example, the policy analyses in Box 6 were both conducted by civil society groups. Investigative journalists and advocacy groups have played a key role in analysing and investigating various parties in various leaks as well as highlighting tax loopholes. [119]

A comprehensive approach to understanding asset ownership

BO information partly overlaps and should be considered along with other types of information, including information from shareholder, trust, and asset registers, to see how these can be brought together to better understand networks of relationships between individuals, entities, and assets. A comprehensive approach involves reducing redundancy and the compliance burden while improving understanding and quality.

Legal arrangements

Although there has been significant progress with the implementation of central BO registers for legal entities, those for trusts and other legal arrangements are less prevalent. Many jurisdictions do not have registration or disclosure requirements for legal arrangements, obfuscating relationships between individuals and assets, and making it difficult to assess the scope of assets owned via legal arrangements. The recommendations set by the FATF do not require either registration or the central collection of information. [120]

In many jurisdictions, the ownership of assets through legal arrangements is still subject to less transparency than assets owned through legal entities. [121] This also means that increased transparency in ownership and control through legal entities may risk displacing tax abuse to asset ownership through legal arrangements.

Within BO networks, trusts are a type of relationship between different parties – individuals or legal entities – and an asset. [122] Trusts assets can include stakes in legal entities, and legal entities can be party to a trust. Therefore, it is necessary to treat both legal entities and arrangements collectively as legal vehicles, and to bring more parity to registration and disclosure requirements for both entities and arrangements as part of a comprehensive approach. In 2024, the EU was one of the first jurisdictions to introduce parity in registration and BO disclosure requirements, as well as access to BO information, for legal entities and arrangements. [123]

Leveraging asset registers

For many of the use cases discussed in this briefing, information about the ownership and control of legal vehicles needs to be connected to information about assets. Jurisdictions tend to have registers for different asset classes – e.g. land and real estate, motor vehicles, and vessels – collecting a range of information, often including legal ownership.

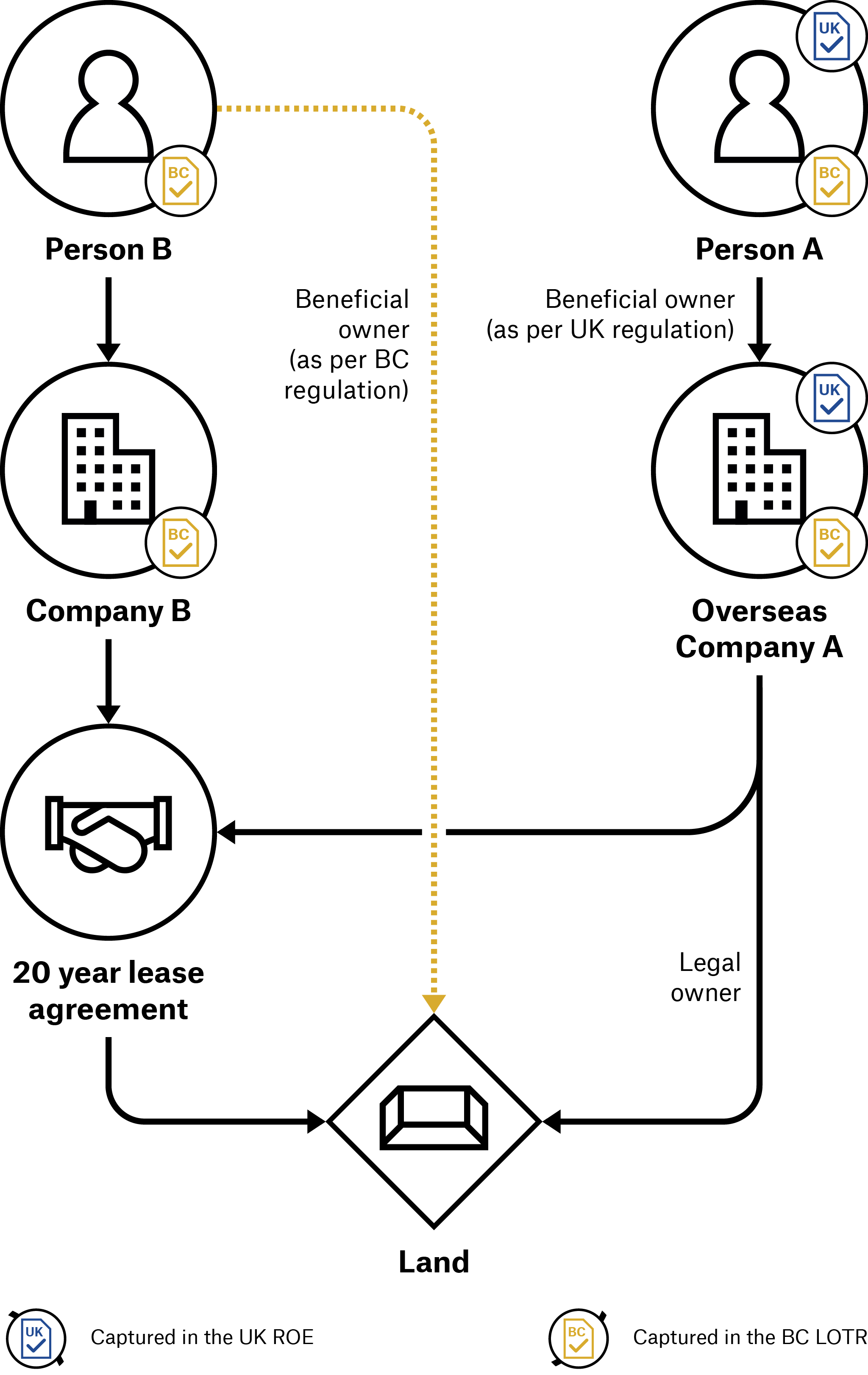

To have better visibility of ultimate ownership and control of these assets, a small number of jurisdictions have implemented BO registers for assets. For example, the Canadian province of British Columbia (BC) and Scotland have set up these registers for land. [124] The registers collect information on the beneficial owners of the assets themselves. Other jurisdictions, like the UK, have set up BO registers for the legal owners of assets. [125] In Argentina, professionals involved in transactions of a range of assets, including land, involving entities report BO information to respective asset registers. [126] These different approaches may yield different information, which can affect how the information can be used or combined (see Figure 3). These pioneering initiatives provide lessons to sketch a way towards better asset transparency.

Figure 3. Diagram showing the difference in scope between the Land Ownership Transparency Register (British Columbia, Canada) and the Register of Overseas Entities (United Kingdom)

In this example, both the UK’s ROE and BC’s Land Ownership Transparency Register (LOTR) would collect information on Overseas Company A as a registered legal owner, including its beneficial owner, Person A. Only the LOTR would capture information on Person B, which has an indirect interest in the land through a lease agreement with Company B, making Person B a beneficial owner of the land under BC legislation. By contrast, the ROE would only capture information about the beneficial owners (as per UK legislation) of the legal owner of the land, where this legal owner is an overseas company.

BO registers for different asset classes may end up collecting information on indirect relationships between individuals and assets without collecting information on intermediaries that may be relevant to tax authorities. However, if asset registers were to start collecting information about intermediaries, there could be significant redundancy of information collected by BO registers for legal vehicles, which may be resource intensive or impossible to compare and consolidate. It would also raise the compliance burden significantly, as legal vehicles may need to report similar information to different government agencies, potentially with different definitions and rules. The collection and verification of information on indirect interests also requires skills and resources that may be better invested in agencies responsible for collecting direct and indirect ownership and control information for legal vehicles, as part of a whole-of-government approach. [127]

Combining information about relationships between people, corporate vehicles, and assets within and across borders efficiently and at scale requires some degree of legal and technical standardisation. Significant progress has been made to achieve this for legal vehicles. [128] For example, legal definitions of BO have been more or less standardised across different frameworks and jurisdictions. Data standards are also being developed to readily combine this information. [129]

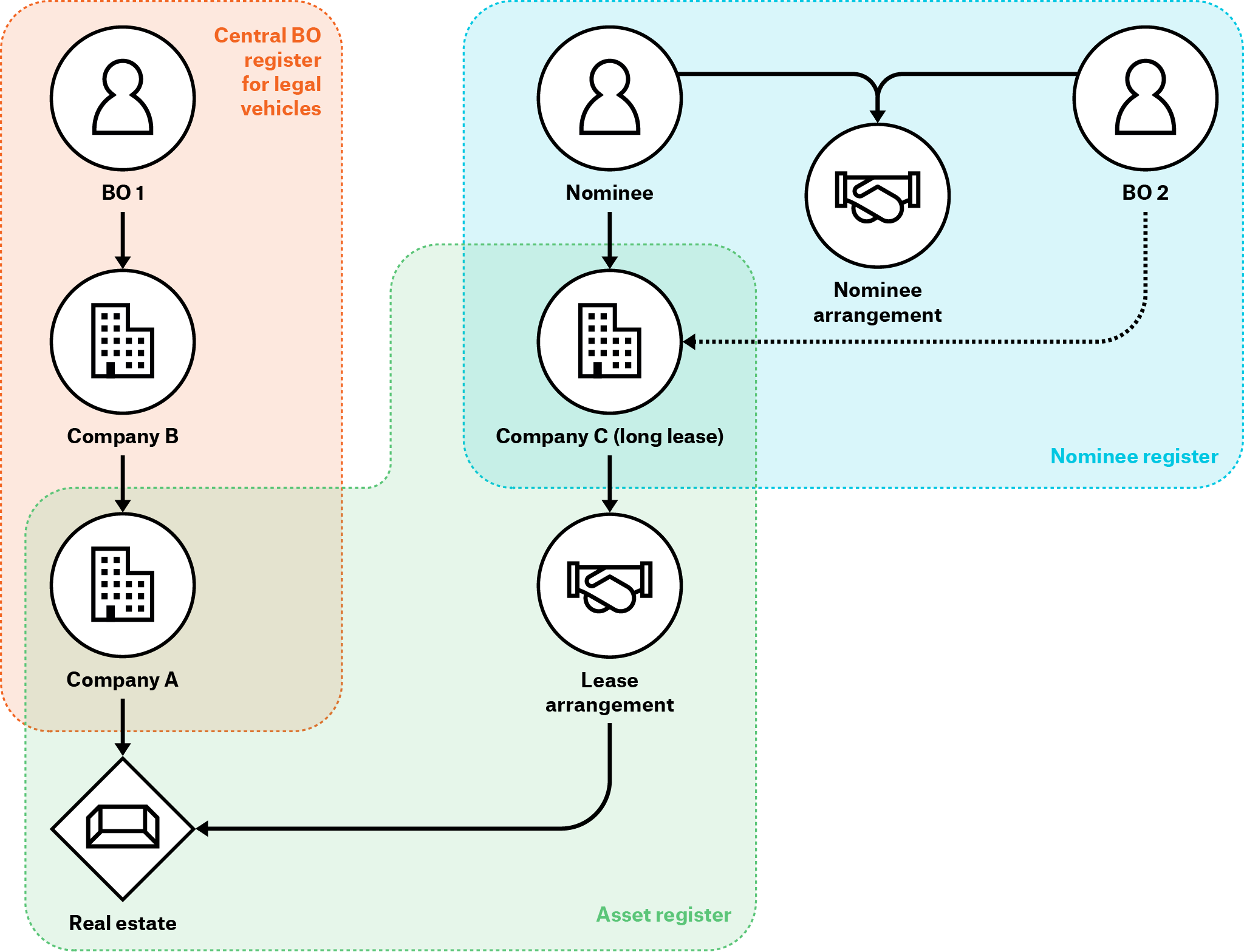

However, this is not yet the case for other asset classes. In order to leverage the progress made with BO of legal vehicles, it would seem sensible to avoid the creation of BO registers for every separate asset class, given the divergence in interests and legal definitions. Instead, jurisdictions wishing to have a clearer picture of the ultimate ownership and control of assets could prioritise connecting BO information for legal vehicles to information on direct interests in asset registers at scale (see Figure 4). This approach is supported by the OECD with respect to real estate: “enhancement to tax transparency could be achieved by associating […] direct ownership information [of real estate] with beneficial ownership information, in cases where the real estate is owned by a legal entity”. [130]

Figure 4. Example connecting beneficial ownership information for legal vehicles to information on direct interests related to assets

Information on direct interests (legal ownership of the asset, a long lease to another party) in real estate are collected in an asset register, and connected to BO information of legal vehicles, and nominees. Where legal entities appear in multiple registers, unique identifiers can help connect the information.

To realise this approach would require defining a common set of minimum information to be included in domestic asset registers. Critically, this information must include reliable identifiers for individuals and legal vehicles so they can be matched across datasets. [131] The minimum information should include legal ownership and additional interests that may be relevant to collect for different asset classes. For example, long-term leases for or the right to use land in the case of real estate, or operators for vessels.

Many asset registers also have a constitutive effect – the fact that ownership is recorded on the register gives legal right to the asset – ensuring accurate and up-to-date information. This is in contrast to a BO register, which is made up of statements, or claims about certain relationships that can be incorrect and difficult to verify. To this end, asset registrars should be involved in the implementation of central BO registers for legal vehicles to ensure this information can be readily connected. All registers should be digitised, with structured and machine-readable information. This is not the reality in many jurisdictions, and is a longer-term aim that will take time and resources. Prioritising certain registers, such as real estate, may be a sensible approach.

Combining BO information for legal vehicles with information on direct interests related to assets is a more effective way to understand BO networks than combining BO information for different asset classes. It is easier to comply with and simpler to verify for accuracy. There is less redundancy of information collection, and it allows jurisdictions to leverage the progress made with BO registers for legal vehicles.

Understanding beneficial ownership networks

BO disclosure requirements fundamentally aim to provide information to understand relationships between individuals and assets for a range of governance objectives, including understanding how legal vehicles operate within society and preventing their misuse. Tax authorities need to understand these relationships to achieve better compliance and inform tax policy. These assets may be legal vehicles themselves (for example, company shares) or otherwise form part of relationships between individuals and assets owned by or through the legal vehicles (for example, assets held through a trust). Many of the use cases presented in this briefing require visibility of full BO networks behind legal vehicles and good legal ownership information. Research shows that this also applies to use cases in other policy areas. [132]

The 2024 survey conducted by the Norwegian Tax Administration echoes this, stating that in cases of complex ownership structures:

Public authorities must obtain information from several different sources, including their own data, registers, third-party information and from the companies. This makes it challenging for public authorities when, in their task solving, they encounter complicated ownership structures across national borders, real estate in Norway that is owned through a company structure where the ultimate owner is hidden, and in other facilities, such as active ownership funds and other facilities for collective investments. [133]

Depending on the level of information collected, BO disclosure can help improve visibility of full BO networks. Where good information on shareholders is available, it can be combined with, and used to verify, BO information to effectively understand more extensive networks of ownership and control without increasing the compliance burden of BO disclosure. To illustrate, in the example in Box 6, shareholder information may have provided a more accurate analysis, good shareholder information was not available whereas BO information was. Jurisdictions should consider reforms to ensure high-quality shareholder information – such as through a centralised shareholder register – can complement BOT reforms. These registers could even be given constitutive effect, where information recorded on the register provides the legal rights to the asset, as is the case with many real estate registers. This ensures information is accurate and up to date.

Details on both direct and indirect relationships contained in BO and shareholder information can be further enriched with information on legal arrangements as well as nominee shareholder and director relationships. [134] The automatic connecting and consolidation of these various information sources will help understand full BO networks without requiring all this information to be collected in a single register.

From exchange to access of information

Currently, tax transparency and the sharing of BO information for legal vehicles mostly operate on the principle of information exchange between jurisdictions. Information is transferred between jurisdictions on demand or in bulk-data transfers on an annual basis. While a significant step forward, this also has obvious drawbacks. The information is not always up to date, it is exchanged by different jurisdictions at different times, and it may take significant resources and capacity to use effectively. [135] Instead, the objective should be for relevant users to have have direct access to relevant information, including BO information of legal vehicles and information about direct interests related to assets. Tax authorities would be able to do their jobs more effectively if they could look up information about relationships between legal vehicles, individuals, and assets when they need to, or ingest this into their systems and combine it with other relevant information.

In practice, there may be challenges with this approach. For example, ARCA has a sophisticated IT system which safeguards the information of the tax administration, and access to external databases by tax officials is limited. Information from the AEOI can be imported into the system and matched with information held by ARCA. However, information from external databases is accessed on a case-by-case basis, and cannot be imported into the system and matched in bulk. Therefore, it is used for risk assessment in only a limited number of cases. [136]

Legal and technical frameworks for accessing information within and across borders need to be further developed. This is already being explored by the OECD for real estate. In reports from 2023 and 2024, the OECD mentions the interconnection of BO registers for legal vehicles at the EU level, and states that “it could be contemplated to then associate the direct, legal ownership registers [for assets] and the beneficial ownership registers [for legal vehicles] with each other, in order to be able to obtain the beneficial ownership information in respect of real estate abroad through a single search”. [137] The authors add that “[w]ith the above enhancements, tax administrations would be able to get efficient, up-to-date and targeted access to both direct ownership and beneficial ownership information in respect of foreign real estate held by their taxpayers. As such, this approach could address the challenges identified and could be an alternative to a model of exchange of information, allowing information to be retrieved real-time, whenever needed by a tax administration”. [138] The reports summarise distinct advantages, including speed of access, data minimisation, and applicability to other agencies and policy areas. [139]

A global asset register

The idea of a global asset register is being explored by civil society and in fora such as the UN’s Financing for Development process as a proposed mechanism to support G20 and UN goals on taxation. [140] There are suggestions that this could be achieved “through interconnecting all national beneficial ownership registries in the world”, requiring “the creation of national beneficial ownership registries which will systematically gather beneficial ownership information across all asset types at the national level”. [141] There are currently significant barriers to being able to do this because of divergence in frameworks and information being collected. It is reasonable to assume the heterogeneity of how assets can be owned, controlled, and benefited from is even larger than that for legal vehicles, which has seen some degree of standardisation.

While the approaches discussed above apply to real estate, where the most progress has been made, they can also be extended to additional asset classes. The approach set out here – standardising and leveraging central BO registers for legal vehicles, standardising the information collected on direct interests by asset registers at the national level, and connecting this information at scale – may also provide a blueprint for the creation of a global asset register. This approach may be more effective and lead to higher-quality information than jurisdictions collecting information about non-domestic legal vehicles owning particular assets themselves (such as the UK ROE), as authorities will be best placed to ensure information is accurate for domestic legal vehicles. [142] Until information is shared effectively across borders, these types of registers may still be useful in the short term.

Footnotes

[112] Open Ownership, Principles for effective beneficial ownership disclosure (Open Ownership, updated 2023), https://www.openownership.org/en/principles/.

[113] A single platform or central register does not necessarily mean that different government agencies and registers should not hold information on different legal vehicles, as long as the information is consolidated and combined, and there is no redundancy and unresolved data conflicts. See: Brun et al., Taxing Crime.

[114] See: Tymon Kiepe, Verification of beneficial ownership data (Open Ownership, 2020), https://www.openownership.org/en/publications/verification-of-beneficial-ownership-data/.

[115] For guidance, see: Favour Ime and Tymon Kiepe, Guide to drafting effective legislation for beneficial ownership transparency (Open Ownership, 2024), https://www.openownership.org/en/publications/guide-to-drafting-effective-legislation-for-beneficial-ownership-transparency/.

[116] For guidance, see: Open Ownership, A guide to doing user research for beneficial ownership systems (Open Ownership, 2024), https://www.openownership.org/en/publications/a-guide-to-doing-user-research-for-beneficial-ownership-systems/.

[117] “Ønsker seg bedre løsninger for å se hvem som eier hva i Norge”, Skatteetaten (Norwegian Tax Administration), 29 January 2024, https://www.skatteetaten.no/nn/presse/nyhenderommet/onsker-seg-bedre-losninger-for-a-se-hvem-som-eier-hva-i-norge/.

[118] Philippines Securities and Exchange Commission, “SuperVision 2028”, n.d., https://www.sec.gov.ph/about-us/plans-and-programs/supervision-2028/.

[119] See, for example: “The Panama Papers: Exposing the Rogue Offshore Finance Industry”, ICIJ, n.d., https://www.icij.org/investigations/panama-papers/; Dan Neidle, UK taxpayers have £570bn in tax haven accounts, and HMRC has no idea how much of this reflects tax evasion (Tax Policy Associates, 2022), https://taxpolicy.org.uk/2022/05/27/crs-evasion/; Dan Neidle, The outrageous £50m tax scheme that was KC-approved. Part 1: The Scheme (Tax Policy Associates, 2023), https://taxpolicy.org.uk/2023/07/03/scheme/.

[120] FATF, The FATF Recommendations, 99–102

[121] See, for example, for the UK and land: UK Government, Department for Levelling Up, Housing & Communities, Department for Business & Trade, HM Treasury, and HM Revenue & Customs, “Chapter 1: The case for change” in Closed consultation: Transparency of land ownership involving trusts, 27 December 2023, https://www.gov.uk/government/consultations/transparency-of-land-ownership-involving-trusts-consultation/transparency-of-land-ownership-involving-trusts.

[122] In some jurisdictions, trusts may have a separate legal personality.

[123] Official Journal of the European Union, AMLD6.

[124] See: Land Owner Transparency Registry, home page, n.d., https://landtransparency.ca/ and Scottish Government, Cabinet Secretary for Rural Affairs, Land Reform and Islands, “Register of persons holding a controlled interest in land”, n.d., https://www.gov.scot/policies/land-reform/register-of-controlling-interests/.

[125] UK Government, Home Office, Department for Business, Energy & Industrial Strategy, Kwasi Kwarteng, Rishi Sunak, and Priti Patel, “News story – New measures to tackle corrupt elites and dirty money become law”, 15 March 2022, https://www.gov.uk/government/news/new-measures-to-tackle-corrupt-elites-and-dirty-money-become-law.

[126] Rodriguez Pratt, Implementación del beneficiario final en economías en desarrollo, 23.

[127] This is explored in further detail in: Tymon Kiepe, “Solving the international information puzzle of beneficial ownership transparency”, Open Ownership, 17 June 2024, https://www.openownership.org/en/blog/solving-the-international-information-puzzle-of-beneficial-ownership-transparency/.

[128] OECD, Strengthening International Tax Transparency on Real Estate – From Concept to Reality, 19.

[129] See, for example: “Beneficial Ownership Data Standard (v0.4)”, Open Ownership, n.d., https://standard.openownership.org/en/0.4.0/.

[130] OECD, Enhancing International Tax Transparency on Real Estate, 23.

[131] Kadie Armstrong and Stephen Abbott Pugh, Using reliable identifiers for corporate vehicles in beneficial ownership data (Open Ownership, 2023), https://www.openownership.org/en/publications/using-reliable-identifiers-for-corporate-vehicles-in-beneficial-ownership-data/.

[132] Julie Rialet, Understanding beneficial ownership data use (Open Ownership, 2025), https://www.openownership.org/en/publications/understanding-beneficial-ownership-data-use.

[133] Government of Norway, Ministry of Finance, “Kartlegging av myndighetenes bruk av opplysninger om eierskap av aksjer og fast eiendom”, 3.

[134] For more information, see: Alanna Markle, Sufficiently detailed beneficial ownership information (Open Ownership, 2025), https://www.openownership.org/en/publications/sufficiently-detailed-beneficial-ownership-information/.

[135] See, for example: Neidle, UK taxpayers have £570bn in tax haven accounts.

[136] Reviewer, 28 January 2025.

[137] OECD, Enhancing International Tax Transparency on Real Estate, 23. Also see: OECD, Strengthening International Tax Transparency on Real Estate – From Concept to Reality.

[138] OECD, Enhancing International Tax Transparency on Real Estate, 22–24.

[139] OECD, Enhancing International Tax Transparency on Real Estate, 23–24.

[140] DESA, Elements paper for the outcome document, 3.

[141] ICRICT, It is Time for a Global Asset Registry, 5.

[142] This is explored in detail in: Alanna Markle, Coverage of corporate vehicles in beneficial ownership disclosure regimes (Open Ownership, 2023), https://www.openownership.org/en/publications/coverage-of-corporate-vehicles-in-beneficial-ownership-disclosure-regimes/.