Leveraging ownership information to improve taxation

Use cases for tax authorities

Due to the increasing availability of BO information for legal vehicles from central registers, there is now more focus on how this – along with other relevant information about relationships between individuals, legal vehicles, and assets – can be leveraged by tax authorities. Based on current practice and examples, this section aims to break down how this information can be used by tax authorities and support their aims, based on current practice and counterfactual examples. Broadly, it is most relevant to tax authorities for the following purposes:

- Closing the tax gap through better compliance: ensuring the right tax is paid, and intervening when there is a risk of that not happening.

- Informing tax policy: developing and delivering policy reforms to tax systems, underpinned by insight and analysis.

Closing the tax gap through better compliance

Compliance is a core function of tax authorities. Broadly, it relates to ensuring the right tax is paid, identifying where there is a risk of that not happening, and intervening in cases of noncompliance. The total difference between the amount of tax that should be paid and what is actually paid is referred to as the tax gap (see Box 1).

Box 1. The tax gap

There are numerous types of noncompliance that contribute to the tax gap, which can be tackled through the use of BO information. [25] These include tax avoidance and evasion. A common distinction between these is that tax avoidance is lawful and tax evasion is illegal. Avoidance involves bending the rules, using them in a way that was never intended, or operating within the letter but not the spirit of the law. The UK describes tax evasion as “an illegal activity where registered individuals or businesses deliberately omit, conceal or misrepresent information in order to reduce their tax liabilities”. [26] Aggressive tax avoidance may be the result of illicit tax and commercial practices. The line between the two is often blurred, and both may give rise to illicit financial flows. [27] Therefore, the term tax abuse can be used to refer to both.

Criminal attacks are another form of tax abuse and also increase the tax gap. This can involve organised groups attacking the tax system in a coordinated and systematic way, for example, through smuggling goods subject to tariffs, or making fraudulent claims on tax refunds such as for value-added tax (VAT). BO information can also help address other forms of noncompliance, including error or failure to take reasonable care, and non-payment.

Information about BO networks can be used to support tax compliance in several ways. First, it can help analyse, assess, and identify risks, raising red flags for potential cases of noncompliance. This can involve looking at patterns and behaviours across known cases of noncompliance, and it can be with respect to characteristics of or changes in ownership, or company structures involving certain types of legal vehicles. A more risk- and evidence-based approach to audits helps focus resources.

Second, the information can support audits and investigations, by using it as intelligence and evidence in investigations and prosecutions; creating legal liability in the case of false statements; and establishing the link between the perpetrator and the tax crime. This may also help identify additional taxpayers and tax liabilities. [28]

Third, identifying risk can be used to encourage compliance and behavioural change. Tax authorities can use BO information for nudge campaigns where insufficient tax has been paid either on purpose, in error, or due to a failure to take reasonable care. For example, in one jurisdiction, the tax authority sent nudge letters to registered taxpayers who had not submitted a tax return or who had declared income as less than a certain amount, and had ceased to be listed as beneficial owners. [29] The letters invited the taxpayer to consider whether “on ceasing control, [the taxpayer] may have disposed of some or all of [their] shares in the company”; if they had, the letters alerted them to the fact that they may have to pay capital gains tax, and provided an opportunity to amend their tax returns. [30]

Finally, information about BO networks helps collect tax debts. For example, if a tax debt has been identified in relation to a non-resident company, information about the beneficial owner can help collect the debt. Box 2 demonstrates how BO information can be used in multiple ways in a single case.

Box 2. Risk detection and investigation of tax fraud schemes in the United Kingdom

An umbrella company is a company that employs a temporary worker, often on behalf of an employment agency, dealing with taxes and payroll. In mini umbrella company (MUC) fraud, organised criminals create multiple umbrella companies, each of which artificially employs a small number of temporary workers. These are set up to pretend to be small employers and fraudulently claim tax reliefs that form part of government incentives for small businesses. The operators of mini umbrella companies then close the companies without paying the correct levels of tax. [31]

A court decision in the UK stated that in a particular investigation, all MUCs “shared common attributes such as their location, postcodes, naming pattern and ownership”, and that “the directors and [beneficial owners disclosed to the company registrar] had originally been UK nationals and residents who subsequently resigned and were replaced as directors and shareholders by individual Filipino nationals resident in the Philippines”. [32] A UK national had signed incorporation documents against payments and was listed as the beneficial owner of nine of the companies before being replaced without the UK national’s awareness. [33] The individual disclosed as the beneficial owner was interviewed by investigators, which formed part of the evidence in the case.

The decision highlights that investigators used “data science tools and techniques to analyse bulk data” to track MUCs, and “while completing a piece of work on non-resident directors, [they] identified a large number of Filipino directors with companies at the same UK Registered Offices”. [34] After this, the investigators “produced a monthly set of outputs to identify MUCs and the links between them” by “taking [BO] data directly from the [company registrar’s] website.” [35]

This example shows how information about company ownership and control can be used to identify risks in real time, and the individuals can form part of investigations. For example, the incorporation of multiple companies in quick succession, sharing similar details (including the same beneficial owner), with a subsequent change in ownership may indicate a MUC fraud scheme, and may merit further investigation.

BO information is fundamentally used to understand relationships. Its use by tax authorities to improve compliance can be divided into the following categories, understanding relationships between:

- parties and taxable assets in cases where assets are hidden;

- parties and taxable income in cases where the source or type of income is hidden;

- parties in transactions or the transfer of assets in cases where the relationship itself is hidden;

- individuals and legal vehicles in criminal attacks on the tax system.

These categories are not necessarily mutually exclusive in individual cases of tax abuse. Rather, they highlight the value of various aspects of BO information in different cases of tax abuse. The categories are further detailed below with supporting examples.

Uncovering hidden assets

Understanding who owns which assets is critical to collecting taxes. In developing economies in particular, taxing assets is more important for equitable taxation. In these economies, more people may be engaged in informal employment than formal employment, meaning they can rely less on income tax – a progressive tax – to the extent that more formalised economies do. Studies show that VAT – a regressive tax – is the main source of income for countries in Africa, the Asia-Pacific region, the Caribbean, and Latin America. [36] This means that taxing assets becomes essential to prevent overreliance on VAT for revenues and more progressive taxation. [37]

Knowing who owns assets is also critical to taxing wealth. [38] Many jurisdictions are considering new taxes on the ultra-wealthy. To illustrate, wealth taxes were a key policy proposal discussed during the 2024 G20 meetings, with estimates that a 2% tax on the wealth of individuals with over USD 1 billion in wealth could raise USD 200–250 billion per year globally. [39] The 2024 G20 Leaders’ Declaration sees leaders seeking to “engage cooperatively to ensure that ultra-high-net-worth individuals are effectively taxed”. [40] In order for wealth taxes to work, it is critical to know who owns which assets (see Box 6).

Identifying taxable assets that are hidden in an attempt to evade taxes is probably the most common use of BO information for tax authorities. Historically, this was often done by offshoring assets to keep them out of sight of domestic tax authorities.

There are numerous examples of tax abuse by offshoring assets (see Box 3). [41] Many of these were revealed by the Panama, Paradise, and Pandora Papers leaks. A European Union (EU) Parliamentary committee’s inquiry into money laundering, tax avoidance, and tax evasion following the Panama Papers found that “the main motivations for the establishment of offshore entities most often include obscuring the origins of money and assets and concealing the identity of the ultimate beneficial owner”, as well as “the avoidance or evasion of inheritance or income or capital gains tax in the countries where the [beneficial owners] are resident […], or leaving the assets transferred to a trust untaxed”. [42]

Box 3. Examples of hiding connections to taxable assets

In 2021, Uganda partly recovered evaded taxes due on the EUR 1.3 million proceeds of sale of shares of a Ugandan company which were hidden in a trust in another country, of which the taxpayer was the beneficial owner. [43]

A Spanish football player offshored image rights to Belize in the early 2000s in an alleged effort to conceal the income from these rights. This resulted in an underpayment of over EUR 2 million in tax between 2007 and 2009. [44]

In the Isle of Man, there was a policy in which VAT refunds were given on the import of private jets into Europe where these were used as part of a genuine business. Multiple shell companies would be set up as part of an artificial leasing enterprise, when individuals would actually be leasing their own private aircrafts to themselves. [45] GBP 790 million was refunded between 2011 and 2017.

The ex-boss of Formula One pleaded guilty to fraud in 2023 over a failure to declare GBP 400 million held in a trust in Singapore to the UK government 18 years previously. He paid over GBP 650 million to settle the matter. [46]

Having better information on the ownership and control networks behind legal entities owning financial and non-financial assets – particularly of foreign assets held by tax residents – would help quickly and proactively detect if taxable assets are hidden, and potentially deter tax abuse.

While some measures (such as the Automatic Exchange of Information (AEOI) discussed in more detail further on) have had success in tackling tax abuse through hiding and offshoring assets, this is limited to financial assets. There are concerns that tax abuse is being displaced to the hidden ownership of non-financial assets, such as real estate, the next policy frontier in tax transparency. The final section of this briefing suggests some concrete ways in which central BO registers for legal vehicles can be leveraged to enable greater transparency in the ownership and control of these assets for better tax compliance.

Revealing the source or type of income

Many taxes are levied based on the source or type of income. For example, income from employment is often taxed differently from income from selling assets or inheritance. Income from taking out a loan is often not taxed at all. Legal vehicles can be used to disguise or alter the source and type of income, which is a form of tax abuse. Round-tripping, where funds are offshored and repatriated, is an example of this. In these cases, the funds are not hidden, but their source or type is disguised to receive advantageous tax treatment. Similarly, individuals can conceal income from employment in so-called disguised remuneration schemes (see Box 4).

Box 4. Examples of disguising the source or type of income

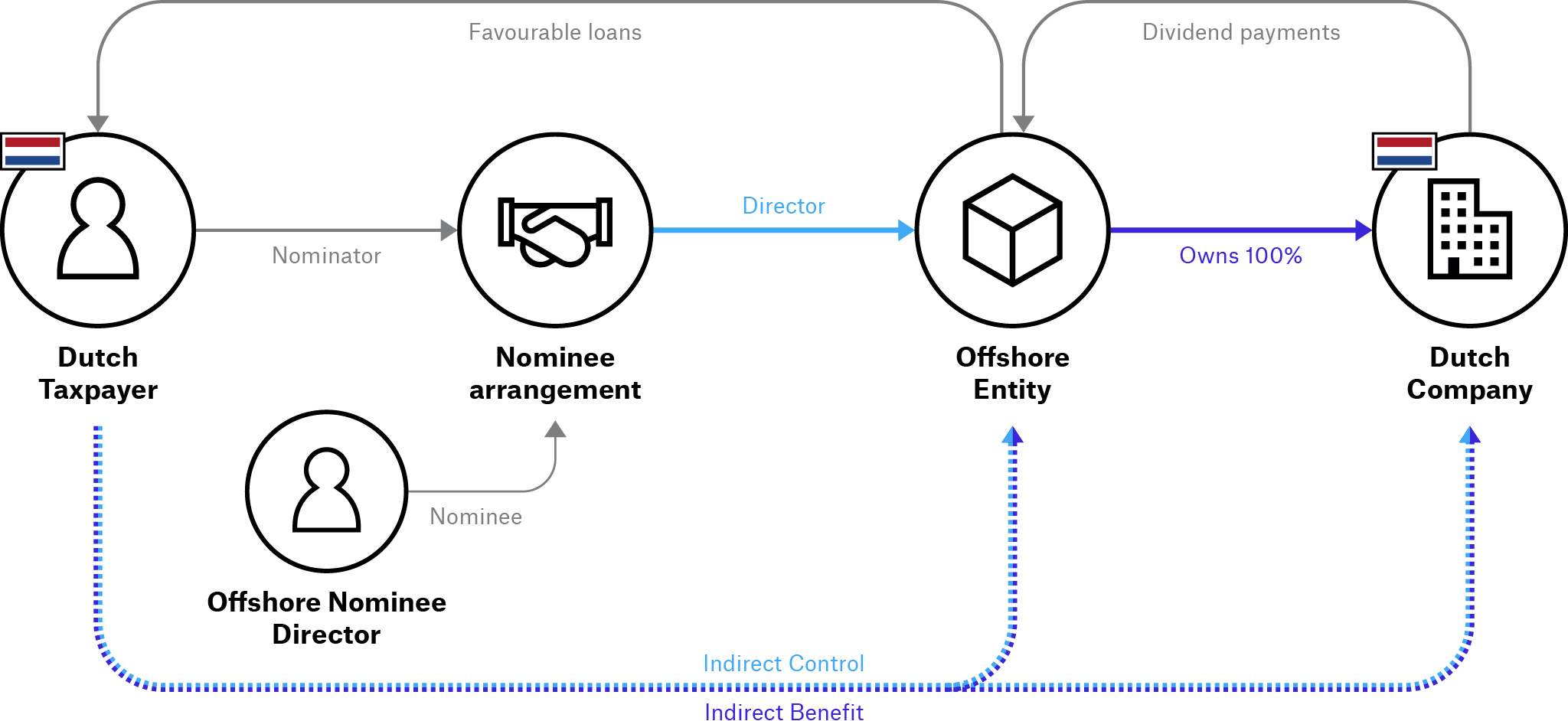

In the Netherlands, a taxpayer sold his sole proprietorship of a business to a Dutch entity, owned by an offshore entity, which is controlled by the taxpayer through a nominee directorship. Payments were then made from the offshore entity to the taxpayer, disguised as gifts or loans with favourable loan conditions (see Figure 1 below). In this way, the taxpayer concealed dividend payments – subject to dividend tax – as loans, thereby evading taxation. [47]

Similar cases in the UK were revealed by the Paradise Papers. In one of these schemes, actors’ income from employment was paid to agents – UK-registered companies – which subsequently transferred the funds to trusts and companies in Mauritius. The actors then borrowed money from these legal vehicles at commercial interest rates. However, the loans and the interest were never repaid. [48] While loans are not taxed in the UK, income from employment is subject to up to 45% taxation and social insurance contributions.

Figure 1. Disguising dividend payments as loans

To attract foreign investment, countries may have preferential tax regimes for non-domestic parties. Tax residents can use round-tripping strategies to disguise domestic capital as foreign investment to abuse these incentives. [49] Better understanding the BO networks behind legal vehicles can help identify cases where income is being misclassed.

Understanding relationships in transfers of assets

Often, transactions or the transfer of assets are subject to taxation, or have certain tax implications. Whether and how parties are connected in these transactions can affect what tax is due. In cases of tax abuse, related parties may conceal a relationship, or feign one. Information on ownership and control networks – including information on both direct and indirect relationships – helps tax authorities to understand these relationships to establish how much tax is due.

Double taxation agreements

DTAs are agreements between countries to ensure that the tax residents of the treaty countries are not taxed twice, often to remove obstacles to cross-border trade and investment. An important stipulation is that the recipient of the treaty benefits (e.g. tax relief) must be the beneficial owner of the income. Without this inclusion, parties tax-domiciled in other jurisdictions may attempt to indirectly access the benefits of a tax treaty between two jurisdictions, for example, by setting up a shell company in one of the jurisdictions. [50]

For DTA enforcement, BO refers to the parties that ultimately receive the payments rather than to the natural persons behind legal vehicles. However, understanding the BO networks behind legal vehicles claiming DTA benefits can also help assess whether treaty benefits are being properly claimed in certain cases, as demonstrated in the example Canada (Box 5).

Box 5. Canada’s Husky Energy case [51]

The Husky Energy case involved three parties disputing Canadian tax assessments related to payments of dividends: A Canadian company, Husky Energy Inc., that paid out the dividends and two shareholders registered in Barbados. The Canadian government claimed the Barbadian companies were the true beneficial owners of these dividends, which were paid initially to two Luxembourg-based companies. These companies had received Husky Energy Inc. shares through a temporary loan agreement with the Barbadian companies. This allowed the Barbadian companies to direct dividend payments to an entity in Luxembourg, for Husky Energy Inc. to take advantage of the DTA and withhold tax on the dividends at a reduced rate of 5%.

However, the Canadian government argued that the Barbadian companies were the actual beneficial owners of the dividends, and that Husky Energy Inc. should have applied a 15% withholding tax rate as per the Canada-Barbados DTA.

A Canadian court ruled partially in the government’s favour, agreeing that the Barbadian companies were the beneficial owners, the reduced tax rate of the Canada-Luxembourg DTA did not apply. However, the court also determined that the Canada-Barbados DTA also did not apply. The Barbadian companies had no Canadian tax liability as they did not directly receive the dividend from a Canadian company, with payments being routed through Luxembourg instead. Therefore, the payment did not qualify for treaty relief in any jurisdiction and the correct withholding rate was Canada’s domestic rate of 25%.

The ruling shows that understanding shareholder relationships between different entities, formal structures and intermediate holding companies, along with the ultimate economic benefit flows, can be essential to enforcing DTAs in certain cases.

Transfer pricing and mispricing

A strategy that can be used for BEPS involves artificially inflated or deflated transactions between two related companies in order to distort taxable income. Because of this, many jurisdictions have rules and methods for pricing transactions within and between businesses under common ownership or control, referred to as transfer pricing. Usually, this permits tax authorities to adjust the value of transactions between companies that are not at arm’s length (i.e. independent) where these have been distorted, possibly in an attempt to evade or avoid tax, referred to as transfer mispricing.

For example, a United States (US) company’s Chilean holding company of a number of Chilean subsidiaries was paying above-market interest rates to a Panamanian bank for a number of loans. However, the bank turned out to be an intermediary, and the US parent company was the ultimate recipient of the interest repayments. [52] In effect, these simulated transactions between apparently independent parties transferred profits out of Chile.

In Argentina, the tax authority Agencia de Recaudación y Control Aduanero (ARCA) (formerly Administración Federal De Ingresos Públicos) oversees the central BO register for legal vehicles. It uses both BO and shareholder information, as well as declarations to generate lists of related parties that are not at arm’s length. This is checked against annual reports from companies on their related parties and used to raise red flags for certain transactions. [53] Information on the ownership and control networks behind legal vehicles is essential to understanding whether or not two parties in a transaction are actually at arm’s length.

Hiding or feigning a transfer of assets

Two parties can transfer assets without changing the legal or direct ownership of the asset. Real estate may be indirectly owned via a company, and that company may be sold to a different party. Without access to sufficient information, it may appear that no transfer of assets has taken place, and a tax on capital gains could be evaded.

In 2007, Vodafone acquired a majority share of an Indian telecommunications business. Vodafone’s Dutch holding entity acquired the Cayman Islands-based holding company that indirectly owned the Indian company. What followed was a decade-long dispute between Vodafone and the Indian government about whether this indirect transfer of assets was subject to capital gains tax. [54] While none of the holding companies were tax residents in India, the underlying assets were. Better information about company ownership networks helps establish when and how indirect transfers of assets take place.

The opposite can also reduce tax liabilities. Legal vehicles can be used to feign the transfer of assets by retaining indirect ownership during a change in legal ownership. In Australia, prior to the introduction of a capital gains tax in the 1980s, a company would sell all its assets to a second company with the same owner when it had a tax liability in so-called “bottom of the harbour” schemes. The original company would then be sold to a proxy for AUD 1, who would destroy the transaction history. The Australian Tax Office investigated this and found around AUD 1 billion in losses. [55]

Countering criminal attacks

The final use case concerns criminal attacks on the tax system, where legal vehicles are often used. This can involve fraudulently claiming tax refunds – such as MUC fraud (see Box 2), non-payment of tax, or smuggling. Information on ownership structures can help detect where these are being established with the intent to commit fraud, and BO information can help track down those responsible.

For example, in the UK, a local administration was owed GBP 7.9 million in unpaid taxes from stores selling counterfeit goods. Shell companies often appeared on the licences and certificates, and neither staff in the stores nor enforcement officers could establish who the beneficial owners were behind the stores. [56] So-called phoenix companies may owe taxes, declare themselves insolvent, and set up a new company to continue the same business without tax-debts. [57] Recently introduced identity-verification requirements for beneficial owners of companies being established in the UK are expected to help local governments find those behind businesses who do not pay their bills, and deter so-called phoenixism. [58]

VAT fraud

VAT fraud has different variations. Missing trader fraud is a form of VAT fraud which involves a company selling goods to a trader free of VAT, which then sells the goods, charges VAT, and subsequently disappears, neglecting its responsibility to pay the VAT to the tax authority. [59]

In VAT carousel fraud, the final purchaser resells the goods to the initial company, then applies for a VAT refund, allowing the same goods to be used in the same scheme again. The companies involved can be incorporated with the sole purpose of perpetrating the fraud, or a missing trader can use unwitting legitimate companies. In the Philippines, the government lost an estimated PHP 50 billion in a VAT fraud scheme involving “dummy corporations” acting as “ghost suppliers” to create fake receipts and fictitious purchase orders to reduce or dodge VAT obligations. [60]

Information on the ownership and control of legal vehicles can both help detect companies with an increased risk of perpetrating this type of fraud based on established patterns and provide leads for investigators when the involved companies disappear. In Denmark, the company registrar, in collaboration with the Danish Tax Agency, has developed a risk model using BO information to flag companies with increased risks of engaging in VAT fraud. [61]

Dividend stripping

Dividend stripping can take a number of forms and may constitute fraud, but broadly refers to short-term sales around the time dividends are paid out. [62] For example, shares can be sold to a related party, with legal ownership temporarily changing without the ultimate economic ownership or control of the shares changing, thereby avoiding dividend tax. [63]

A form of dividend stripping is the cum-ex trading scheme, which is estimated to have cost the German treasury USD 32.6 billion. [64] In simple terms, the scheme involved parties briefly transferring legal ownership of shares in large companies – usually through a series of rapid trades just before dividend payouts – without transferring beneficial ownership. To tax authorities, there appeared to be multiple owners of the shares, but there was only one. Multiple parties would then claim refunds on the tax withheld on dividend payments and share the profits. [65] Parties that briefly assume legal ownership without acquiring the economic interest are often not entitled to a dividend-withholding tax refund. [66]

While information held in central BO registers for legal vehicles as they are currently set up would be unlikely to help with this type of abuse, accurate and up-to-date information on direct ownership of shares over time as well as ultimate control of and economic benefit from shares could help detect and prevent some of these schemes. Potential pathways towards achieving this are explored below.

Informing tax policy

Another core function of many tax authorities is to develop and deliver policy reforms to the tax system, based on analysis and an understanding of tax collected as well as potential tax to collect. BO information helps understand the distribution of wealth and assets in a country, and therefore provides insights into the real and potential tax base of an economy. [67] This can help form the basis for more progressive taxation.

Analysis of information on the ownership and control networks behind legal vehicles, including BO information, can help evaluate existing policies. It can also inform new evidence-based tax policy, as it provides insights into the concentration and distribution of taxable wealth and assets. This is illustrated by two recent examples from the UK (Box 6).

Box 6. Assessing proposals for and potential revenue gains of new tax policies in the United Kingdom

In 2020, a Wealth Tax Commission was established to provide in-depth analysis of proposals for a UK wealth tax. [68]

Various reports by the Commission made use of BO information from the UK’s central register, including to estimate the value and liquidity of private businesses for wealth taxation and assess to what extent UK businesses had complex ownership structures, with implications for how dividends could be extracted from businesses. [69] Another study used BO information to explore the administration of annual taxes on dwellings held within a corporate structure. [70] Finally, the Commission argued that BO information is critical to administering a wealth tax, particularly on assets such as real estate and in cases of non-resident ownership. [71] It also argued that BO information would help enforce a potential wealth tax on controlling shareholdings in UK unlisted companies held by non-residents. [72]

These findings are echoed in OECD proposals that include leveraging BO information to ensure tax authorities have better information about real estate held off-shore by taxpayers, constituting a significant amount of wealth. [73] This would address one of the Commission’s key recommendations with respect to BO.

In 2024, a quantitative study used BO information to analyse major shareholdings to assess the potential tax gains of introducing an exit tax in the UK. [74] An exit tax is a tax on people who leave the country after making substantial capital gains while living there. While many countries have this tax, the UK currently does not. [75] In the UK, anyone emigrating after more than five years can currently take all of their unrealised gains with them fully tax-free.

By investigating major shareholders of UK companies who changed residence in the twelve-month period from April 2023 to April 2024, as well as where they went, the study was able to assess how much capital gains tax revenue was potentially lost. It found a net outflow of at least GBP 5.1 billion in shareholding value, leading to at least GBP 500 million in foregone revenue. The study found that in addition to substantial revenue lost, most leavers go to zero capital gains tax jurisdictions, and most of the tax gains come from a small number of leavers. [76] On this basis, the paper is able to make fair and economically efficient tax policy recommendations in favour of an exit tax.

Footnotes

[25] This framing is based on: UK Government, HM Revenue & Customs, “Chapter L”.

[26] UK Government, HM Revenue & Customs, “Chapter L”.

[27] Antony Seely, Tax avoidance and tax evasion (UK Government, House of Commons Library, 2021), https://researchbriefings.files.parliament.uk/documents/CBP-7948/CBP-7948.pdf; UNODC and UNCTAD, Conceptual framework for the statistical measurement of illicit financial flows (UNODC and UNCTAD, 2020), 12, https://www.unodc.org/documents/data-and-analysis/statistics/IFF/IFF_Conceptual_Framework_FINAL.pdf.

[28] Rodriguez Pratt, Implementación del beneficiario final en economías en desarrollo, 20.

[29] James Selby, “HMRC Targets”, Whitings LLP, 23 August 2020, https://whitingsllp.co.uk/beware-hmrc-nudge-letters/.

[30] UK Government, Companies House, Capital Gains Tax on Share Disposals letter template, n.d., https://assets-eu-01.kc-usercontent.com/220a4c02-94bf-019b-9bac-51cdc7bf0d99/c101318a-3781-4694-8a3d-71e263ef6238/UPS042%20-%20Final%20Letter.pdf.

[31] UK Government, HM Revenue & Customs, “Guidance: Mini umbrella company fraud”, updated 3 December 2024, https://www.gov.uk/guidance/mini-umbrella-company-fraud.

[32] First-Tier Tribunal – Tax Chamber, 2024 UKFTT 00291 (TC), Case Number: TC 09126, Taylor House, London, 27 March 2024, 53, https://assets.caselaw.nationalarchives.gov.uk/ukftt/tc/2024/291/ukftt_tc_2024_291.pdf.

[33] 2024 UKFTT 00291 (TC), 16.

[34] 2024 UKFTT 00291 (TC), 4.

[35] 2024 UKFTT 00291 (TC), 4.

[36] “Global Revenue Statistics Database”, OECD, updated 6 December 2024, https://www.oecd.org/en/data/datasets/global-revenue-statistics-database.html.

[37] Rodriguez Pratt, Implementación del beneficiario final en economías en desarrollo, 8–9.

[38] Wealth taxes can take different forms. See: Zimbali Mncube and Diana Mochoge, The taxation of wealth for the eradication of poverty and inequality (African Forum and Network on Debt and Development, 2024), https://afrodad.org/news-events/articles/taxation-wealth-eradication-poverty-and-inequality.

[39] Gabriel Zucman, A blueprint for a coordinated minimum effective taxation standard for ultra-high-net-worth individuals (Gabriel Zucman (commissioned by the Brazilian G20 Presidency), 2024), 1, https://gabriel-zucman.eu/files/report-g20.pdf.

[40] G20 Brazil 2024, “G20 Rio de Janeiro Leaders’ Declaration”.

[41] For more information on the Panama, Paradise, and Pandora Papers leaks, see: International Consortium of Journalists, home page, n.d., https://www.icij.org/.

[42] Petr Ježek and Jeppe Kofod, REPORT on the inquiry into money laundering, tax avoidance and tax evasion, A8-0357/2017 (European Parliament, 2017), https://www.europarl.europa.eu/doceo/document/A-8-2017-0357_EN.html.

[43] African Union, African Tax Administration Forum (ATAF), and OECD, Tax Transparency in Africa 2022: Africa Initiative Progress Report (OECD, 2022), 61, https://web-archive.oecd.org/tax/transparency/documents/tax-transparency-in-africa-2022.pdf.

[44] Margarita Santana Lorenzo, “El problema del fraude fiscal: El caso Leo Messi”, Santana Lorenzo, n.d., http://santanalorenzo.com/blog/el-problema-del-fraude-fiscal-el-caso-leo-messi.

[45] Juliette Garside, “How Isle of Man gives big refunds to super-rich on private jet imports”, The Guardian, 6 November 2017, https://www.theguardian.com/news/2017/nov/06/isle-of-man-refunds-super-rich-private-jets-paradise-papers.

[46] Henry Vaughan, “Ex-Formula One boss Bernie Ecclestone avoids jail after pleading guilty to fraud”, Sky News, 12 October 2023, https://news.sky.com/story/ex-formula-one-boss-bernie-ecclestone-admits-fraud-12982939.

[47] OECD, Ending the Shell Game: Cracking down on the Professionals who enable Tax and White Collar Crimes (OECD, 2021), 14, https://www.oecd.org/content/dam/oecd/en/publications/reports/2021/02/ending-the-shell-game_79ff90e4/79e22c41-en.pdf.

[48] Hilary Osborne, “Mrs Brown’s Boys stars used web of offshore companies to avoid tax”, The Guardian, 6 November 2017, https://www.theguardian.com/news/2017/nov/06/mrs-browns-boys-stars-used-web-of-offshore-companies-to-avoid-tax.

[49] Markus Meinzer, Mustapha Ndajiwo, Rachel Etter-Phoya, and Maïmouna Diakité, Comparing tax incentives across jurisdictions: a pilot study (Tax Justice Network, 2019), 8, https://www.taxjustice.net/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/Comparing-tax-incentives-across-jurisdictions_Tax-Justice-Network_2019.pdf.

[50] “Preventing tax treaty abuse”, OECD, n.d., https://www.oecd.org/en/topics/sub-issues/preventing-tax-treaty-abuse.html.

[51] Leticia de Moura and Melle van der Stoel, “An interpretation of the Beneficial Ownership Concept following Canada’s Husky Energy Case”, RSM, 20 November 2024, https://www.rsm.global/netherlands/en/insights/interpretation-beneficial-ownership-concept-following-canadas-husky-energy-case.

[52] Juan Andrés Guzmán, “‘Papeles del Paraíso’: filtraciones refuerzan postura del SII en millonario juicio contra Walmart”, CIPER, 10 November 2017, https://www.ciperchile.cl/2017/11/10/papeles-del-paraiso-filtraciones-refuerzan-postura-del-sii-en-millonario-juicio-contra-walmart/.

[53] Interview between Open Ownership and a former employee at ARCA, 25 October 2023, online.

[54] Nikos Lavranos, “Vodafone v India award: risky business of retroactive taxation”, Thomson Reuters, Practical Law Arbitration Blog, 21 December 2020, http://arbitrationblog.practicallaw.com/vodafone-v-india-award-risky-business-of-retroactive-taxation/.

[55] The Rebel Accountant (anon.), Taxtopia: How I Discovered the Injustices, Scams and Guilty Secrets of the Tax Evasion Game (Octopus Publishing Ltd., 2023), 157.

[56] “Oxford Street: US sweet shops will never pay £7.9m tax bill, says council”, BBC News, 8 July 2022, https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-england-london-62090601.

[57] UK Parliament, Committee of Public Accounts, Ninth Report of Session 2024–25, “Summary – Tax evasion in the retail sector”, 12 February 2025, https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm5901/cmselect/cmpubacc/355/report.html.

[58] Aletha Adu, “Labour to crack down on ‘dodgy’ candy stores in push to revive high streets”, The Guardian, 25 December 2023, https://www.theguardian.com/politics/2023/dec/25/labour-to-crack-down-on-dodgy-candy-stores-in-push-to-revive-high-streets.

[59] Marie Lamensch and Emanuele Ceci, VAT fraud: Economic impact, challenges and policy issues (European Parliament, Policy Department for Economic, Scientific and Quality of Life Policies Directorate-General for Internal Policies, 2018), 15–16, https://www.europarl.europa.eu/cmsdata/156408/VAT%20Fraud%20Study%20publication.pdf.

[60] Jacob Lazaro, “Gov’t lost P50 billion to tax fraud; 30 people charged”, Philippine Daily Inquirer, 21 May 2023, https://newsinfo.inquirer.net/1772045/govt-lost-p50b-to-tax-fraud-scam-30-people-charged; Government of the Philippines, Nineteenth Congress of the Republic of the Philippines – First Regular Session, 29 May 2023, 4, https://web.senate.gov.ph/lisdata/4186838137!.pdf.

[61] Christian Hattens, Beneficial Ownership: Experiences from the Danish implementation of an Beneficial Ownership Register (Transparency International Denmark, 2022), 4, https://transparency.dk/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/TI-Beneficial-Owners-Conference-report-Experiences-from-Denmark.pdf.

[62] It should be noted that dividend arbitrage trading schemes are not possible in some jurisdictions and, where they are possible, they are not always treated as tax crimes. See: European Banking Authority (EBA), Action plan on dividend arbitrage trading schemes (“Cum-Ex/Cum-Cum”) (EBA, 2020), 2, https://www.eba.europa.eu/sites/default/files/document_library/News%20and%20Press/Press%20Room/Press%20Releases/2020/EBA%20publishes%20its%20inquiry%20into%20dividend%20arbitrage%20trading%20schemes%20%28%E2%80%9CCum-Ex/Cum-Cum%E2%80%9D%29/883617/Action%20plan%20on%20dividend%20arbitrage%20trading%20schemes%20Cum-ExCum-Cum.pdf.

[63] Dinesh Naik and Rebecca Simpson-Heine, “KPMG Tax Chat: Restructure At Your Own Peril”, KPMG, n.d., https://assets.kpmg.com/content/dam/kpmg/nz/pdf/Aug/Dividend-Stripping.pdf.

[64] Ragnhild Vartdal, “Norge rammet av europeisk skatteskandale”, NRK, 18 October 2018, https://www.nrk.no/urix/norge-rammet-av-europeisk-skatteskandale-1.14253588.

[65] “Cum-Ex Trading Schemes Explained & FAQs”, Rahman Ravelli, n.d., https://www.rahmanravelli.co.uk/expertise/cum-ex-investigations/cum-ex-trading-schemes-explained-and-faqs/.

[66] Financieel Expertise Centrum, Kennisdocument Dividendstripping Extern (Financieel Expertise Centrum, 2021), 8, https://www.fec-partners.nl/media/yifblbh0/20211119-kennisdocument-dividendstripping-extern.pdf.

[67] Rodriguez Pratt, Implementación del beneficiario final en economías en desarrollo, 36.

[68] Wealth Tax Commission, home page, n.d., https://www.ukwealth.tax/.

[69] Hannah Tarrant, Valuation and liquidity issues for private businesses: quantitative evidence – Background paper no. 125 (Wealth Tax Commission, 2020), https://www.wealthandpolicy.com/wp/BP125_PrivateBusinesses.pdf.

[70] Edward Troup, John Barnett, and Katherine Bullock, The administration of a wealth tax – Evidence paper no. 11 (Wealth Tax Commission, 2020), https://www.wealthandpolicy.com/wp/EP11_Administration.pdf.

[71] Louise Russell-Prywata, Beneficial ownership and wealth taxation: an assessment of the availability and utility of beneficial ownership data on companies in the administration and enforcement of a UK wealth tax – Background paper no. 124 (Wealth Tax Commission, 2020), https://www.wealthandpolicy.com/wp/BP124_BeneficialOwnership.pdf; Arun Advani, Emma Chamberlain, and Andy Summers, A wealth tax for the UK – Final report (Wealth Tax Commission, 2020), 70, 122–23, https://www.wealthandpolicy.com/wp/WealthTaxFinalReport.pdf.

[72] Advani et al., A wealth tax for the UK, 123.

[73] OECD, Strengthening International Tax Transparency on Real Estate – From Concept to Reality: OECD Report to G20 Finance Ministers and Central Bank Governors (OECD, 2024), https://www.oecd.org/content/dam/oecd/en/publications/reports/2024/07/strengthening-international-tax-transparency-on-real-estate-from-concept-to-reality_abb45622/fa2db2a4-en.pdf.

[74] Arun Advani, Cesar Poux, and Andy Summers, Business owners who emigrate: Evidence from Companies House records (Centre for the Analysis of Taxation, 2024), 2, https://centax.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2024/10/AdvaniPouxSummers2024_BusinessOwnersWhoEmigrate.pdf.

[75] Some countries with an exit tax include: Australia, Canada, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Ireland, Japan, Luxembourg, Netherlands, Norway, South Africa, Spain, Sweden, and the United States.

[76] Advani et al., Business owners who emigrate, 4–6.