Measuring the economic impact of beneficial ownership transparency (summary report)

Introduction

Beneficial ownership transparency (BOT) involves governments collecting beneficial ownership information [1] and making this information available to actors within and outside of government, such as law enforcement or the general public. Beneficial ownership data can be used to tackle issues around corporate accountability and illicit financial flows, and to enforce sanctions against corrupt officials, or actors accused of complicity in human rights abuses. [2]

The nature of BOT regimes varies significantly across jurisdictions. However, Open Ownership has started to identify emerging good practice in implementation in its Principles for effective disclosure. [3] Broadly summarised, these principles state that data should be comprehensively collected and disclosed, freely available in a central register, and periodically verified, with sanctions enforced for non-compliance with disclosure obligations. Open and free-to-access BOT registers such as the UK’s PSC (Person of Significant Control) register are examples of emerging best practice in this area, even though no register to date fully meets all of the requirements set out in the Open Ownership Principles.

Since the introduction of the first standards on beneficial ownership transparency published by the Financial Action Task Force (FATF) in 2003, BOT has gathered international momentum, with more than 113 countries having made commitments to collect more information about the individuals who own or control registered legal entities. [4] A few dozen have also created centralised beneficial ownership registers to house this information, particularly after the European Union’s 5th Anti Money Laundering Directive mandated EU states to do so in 2015. [5] [6]

However, despite this surge in reforms intended to increase beneficial ownership transparency, there remains only a limited body of research which seeks to assess the impact of BOT interventions, and even less work that quantitatively measures the economic impacts of BOT.

Methodologically sound quantitative economic evidence for BOT could enable better informed discussions about the broader impacts and benefits of reform. As such, Open Ownership has identified a need to explore potential methods for measuring the economic impact of BOT, which forms the backdrop of this landscaping study.

This summary report provides high level insights into our full report, which tackles a number of key research questions, including:

- What types of economic benefits can we expect from BOT policies?

- How can we measure the scale of the economic benefits of BOT?

- What has been done so far to measure the benefits of BOT?

- How might quantitative evidence be used to advance BOT policymaking in the future?

Measuring the economic impact of BOT is not straightforward. Neighbouring research teaches us that quantifying the impact of anti-corruption initiatives in general is challenging given the clandestine nature of criminal financial activities, the indirectness and diffuseness of the impacts, and the difficulties of attributing benefits to specific interventions. [7] This report acknowledges the ambitious nature of this task, and is candid about the trade-offs involved in the various approaches to economic quantification.

Methodological note

This project’s research methodology can be broadly divided into three phases:

- Definitions and logic modelling. During the initial phase of the project, we worked to establish clear definitions of BOT, its specific policy objectives and implementation types, which could be used as a solid foundation for approaches to measurement. We also mapped out the kinds of benefits that can be logically derived from BOT using logic modelling, an approach explored in further detail in this summary report. This was supported by insights from desk research and expert interviews outlined below.

- Literature review. We conducted a review of existing work exploring the economic impact of BOT (of which we found very limited examples) and material which is more sceptical about the potential for robust econometric analysis. Given the limited literature specifically focussed on the economic impact of BOT, we also looked to analogous policy areas, including fiscal transparency and open contracting, which produce similar benefits through similar mechanisms. The literature review is detailed further in our main report.

- Interviews. Finally, we also conducted semi-structured interviews with experts from beneficial ownership advocacy organisations, academia, and government. Some interviews were specifically tailored to participants' previous work, in order to deepen our understanding of the research landscape. We additionally returned to some of the experts to discuss the approaches and recommendations identified and to solicit feedback, which has since been incorporated into this report.

This summary outlines the headline findings of the report and sets out key recommendations for governments regarding measuring the economic benefits of beneficial ownership transparency.

Defining the expected benefits of a BOT intervention: a logic model approach

To anticipate the kinds of benefits which should arise from different BOT reforms, we used a logic modelling approach. Logic models are graphic representations of the ways an intervention creates impact through causal chains of inputs, activities, outputs and outcomes. [8]

Logic models have been used in the UK government’s discussions of BOT benefits. A BEIS Post-implementation review of the UK PSC register from 2019 uses a basic descriptive logic model to highlight the relationship between context, inputs, outputs, outcomes and impacts associated with the implemented regulations. [9] We chose to build upon this framework by expanding the model into a larger logic map which helped us identify the specific mechanisms by which various types of BOT interventions lead to economic benefits. The model was then updated iteratively over the course of research, with new benefits, or causal mechanisms identified in interviews with experts and desk research.

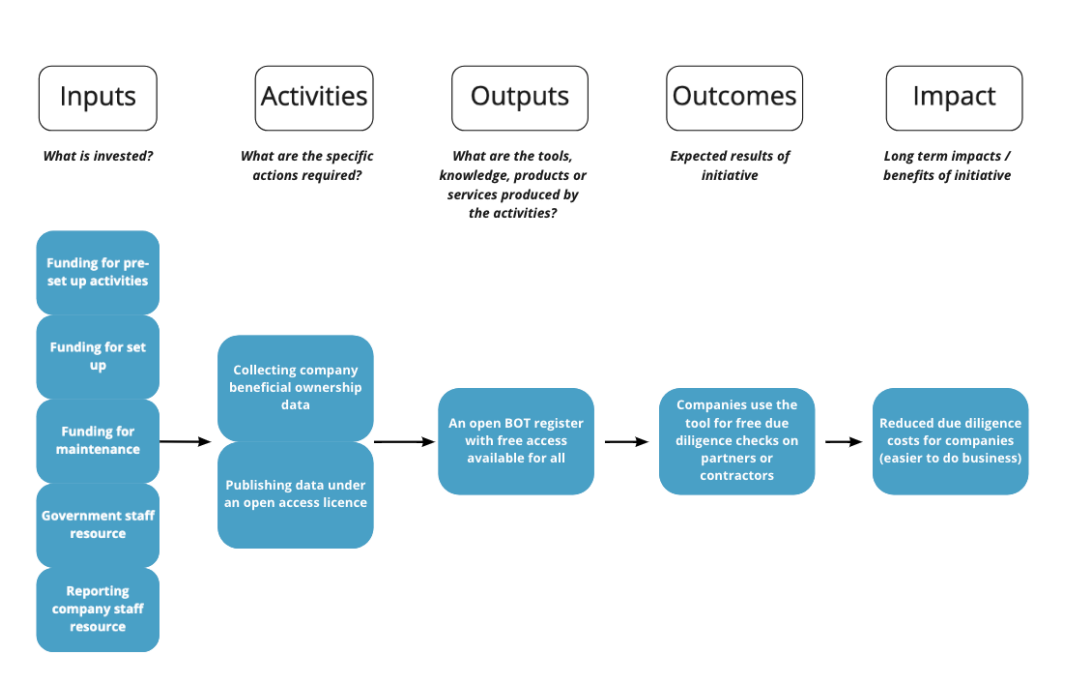

A further function of logic modelling was to demonstrate how particular implementation design choices, such as the decision to make a register free, or provide an API, can lead to specific benefits, which are excluded or weakened in the case of less effective implementation types. Below we have included an exemplary chain from the logic model which represents how a specific design choice, in this case making a register freely accessible, can lead to reduced due diligence costs for companies.

In this example, “inputs” or resources invested, enable “activities” – collecting company and publishing data under an open access licence. This in turn creates an “output”, a BOT register with free access for all, which leads to the outcome of companies being able to use the register to perform elements of due diligence for free. Finally, the financial impact or benefit is that due diligence costs will be reduced for companies, who in this scenario, can turn to a BOT register as a free-to-access resource for helping research the financial backgrounds of prospective partners and contractors.

A full version of the logic model which supported this research is available here. Note that the benefits outlined are not exhaustive; given that BOT is still a relatively nascent policy area, there may even be unexpected economic benefits of reform which are yet to be felt or documented. Nonetheless, the benefit categories outlined in the model were most commonly identified in literature and interviews and function as a good starting point for a discussion of potential approaches to impact quantification.

Footnotes

[1] Open Ownership defines a beneficial owner as “a natural person who has the right to some share or enjoyment of a legal entity’s income or assets (ownership) or the right to direct or influence the entity’s activities (control)”. See: Open Ownership. (2020). Beneficial ownership in law: Definitions and thresholds.

https://www.openownership.org/uploads/oo-briefing-bo-in-law-definitions-and-thresholds-2020-10.pdf

[2] Open Ownership. What is beneficial ownership transparency? Accessed March 2022. https://www.openownership.org/en/about/what-is-beneficial-ownership-transparency/#:~:text=A%20beneficial%20owner%20is%20a,controlled%20by%20their%20beneficial%20owners.

[3] Open Ownership. (2021). The Open Ownership Principles.

https://www.openownership.org/uploads/oo-guidance-open-ownership-principles-2021-07.pdf

[4] Open Ownership. Worldwide commitments and action map. Accessed January 2022.

https://www.openownership.org/map/#map

[5] Ibid.

[6] Official Journal of the European Union. (2015). Directive (EU) 2015/849 of the European Parliament and of the Council. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:32015L0849&from=EN

[7] Department for International Development. (2015). Evidence Paper: Why Corruption Matters: understanding causes, effects and how to address them. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/406346/corruption-evidence-paper-why-corruption-matters.pdf

[8] For a discussion of logic modelling and definitions of each stage in the process, see this logic model template published by the Open Data Institute.

[9] Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy (BEIS). (2019). Post-Implementation Review of the People with Significant Control Register. https://www.legislation.gov.uk/uksi/2017/694/pdfs/uksiod_20170694_en.pdf