Sufficiently detailed beneficial ownership information

Achieving the registrar’s three main objectives

A registrar has three main objectives when processing the BO information it gathers, and it needs a sufficient level of detail to do so. As mentioned earlier, these objectives are:

- verifying the identity of individuals and legal vehicles;

- understanding relationships between individuals and legal vehicles; and

- ensuring BO information is auditable and usable.

Determining how to achieve these objectives most effectively is the primary consideration for choosing which information fields should be collected or retrieved as part of a BO declaration.

Verifying the identity of individuals and legal vehicles

The level of detail in a BO declaration should be sufficient for a registrar to be able to verify the identities of individuals and legal vehicles involved. Verification of BO information is done through the checks and processes used to reach a good level of confidence that the information declared to and recorded in a register is an accurate and complete representation of the real ownership structure of a company. [29]

Identity verification is a core aspect of this, and involves determining the real-world individual or entity to which the reported natural person or legal vehicle corresponds, if any. Identification attributes are pieces of information that help with identity verification. To reach a high level of assurance for verification, the registrar needs a combination of attributes that can be triangulated and cross-checked as part of the verification process, at least one authoritative reliable identifier with a reliable and accessible provenance, or a combination of these.

For example, names are a common identification attribute, but different individuals or entities can have similar or identical names. The misspelling, abbreviation, or imitation of a name can also be misleading, whether done accidentally or intentionally (Box 5). For natural persons, names can also change due to personal choices, such as marriage. For legal vehicles, events like rebrands, mergers, and partnership formations can also complicate the identification of legal vehicles by name only. [30] When an original name is not written in an official or commonly used language of the jurisdiction where a BO declaration is being made, transliteration should be required to ensure it is understandable to the registrar and data users. However, this process can also introduce new variations in how it is written.

In contrast, a reliable identifier is a unique number or reference code that stays the same over time. A reliable identifier is an attribute that can provide a higher level of confidence that one declaration subject is different from another, and that it corresponds to a known individual or entity in the real world. It also helps establish whether records about individuals and legal vehicles within the same or in different information sources are referring to the same, or different individuals and legal vehicles. When authoritative, collecting a reliable identifier can be used as the primary means of identity verification, especially for legal vehicles. When shared with data users beyond the registrar, reliable identifiers can also make data more usable, as discussed below.

Box 5. Use of ambiguous naming conventions for potential tax avoidance [31]

An accountant formerly working in international tax mitigation reported having a client with a group structure of over 150 companies. The majority of these had near-identical names, such as “A1A A1A Limited, A1AA1 Limited, 1AAA1 Limited, AA1AA GmbH, A1A1A Limited”. In this case, the entities were transferring funds between one another, and the structure and naming convention may have been made intentionally confusing as a means of facilitating tax avoidance. A transfer request between two of the entities, worth several million dollars, was at one point flagged by the bank for AML checks.

Identifying natural persons

Identity verification of natural persons is often understood as seeking to achieve a commensurate level of assurance that a claim to a particular identity can be trusted to be the claimant’s true identity, typically relying on multiple pieces of information to achieve the required standards. [32] The World Bank points to three potential levels of identity assurance:

Low (level 1): Self-asserted identity (e.g., email account creation on web), no collection, validation or verification of evidence.

Substantial (level 2): Remote or in-person identity proofing (e.g., provide credential document for physical or backend verification with authoritative source), address verification required, biometric collection optional.

High (level 3): In-person (or supervised remote) identity proofing, collection of biometrics and address verification mandatory. [33]

Guidance issued by the Financial Action Task Force (FATF) on effectively implementing BO registers for the purposes of AML suggests a minimum of either: government-issued identity documents being provided to the registrar, along with verification of their authenticity; or attributes being verified with government-held registers, including passport registers. [34] This correlates with the substantial level (level 2) in the World Bank framework. However, registrars may choose to exceed this and pursue the maximum available level of identity verification depending on their context.

Regardless of the approach, the use of identification attributes, including reliable identifiers that appear in identity documents, is fundamental to identity verification. In fact, the FATF defines identity as “a combination of ‘attributes’ that belong to a person”. [35] Examples of reliable identifiers for individuals that are collected by registrars include passport numbers, social security numbers, national ID numbers, and tax identification numbers (Box 6). Other identification attributes can be collected in information fields like name, date of birth, nationality, and place of birth. [36]

Some jurisdictions also choose to assign unique numbers to beneficial owners once their identities are verified. These unique numbers can be used again in subsequent submissions as reliable identifiers (Box 7). This can be an effective means of ensuring individuals and legal vehicles have a permanent form of identification within the BO register, enabling ease of identification for both the registrar and data users. Depending on the implementation, it may also help to protect privacy when the reliable identifier the registrar assigns does not have any use or significance outside the register, as it can enable data use without the need to publish information about a natural person’s other attributes.

Identifiers play a key role in helping data users understand relationships between subjects within and across information sources, as discussed below. This requires sufficient information to easily determine whether records about individuals, legal vehicles, and assets refer to the same or different subjects, to accurately establish relationships between these subjects within and across datasets. The lack of common identifiers can make this very resource intensive. Having common identifiers across jurisdictions for legal vehicles is far more feasible than for natural persons, but publishing register-issued identifiers for natural persons at the national level can nevertheless help improve the efficiency of the data ecosystem.

Box 6. Collecting reliable identifiers for beneficial owners

In 2022, a study with EU member states found that each state required officially issued identifiers for beneficial owners in at least some circumstances. In over half of member states, officially issued identifiers were required in all circumstances. In other member states, these identifiers were only required under particular circumstances, such as when the beneficial owner was not a citizen. At least 15 also required supporting evidence or documentation in at least some circumstances, namely when the beneficial owner was not a domestic citizen. The study also found that the collection of identifiers was often linked to their use to confirm a beneficial owner’s identity against domestic databases. [37]

This is also common practice outside the EU. For example, China is collecting information on the type, number, and validity period of a person’s identity-or identity-certification document. [38] Malawi’s BO declaration form includes fields for legal identification type and number. [39] Armenia requires the collection of identity-document data and social security numbers for residents; for foreign natural persons, a copy of their passport or other identification document, authenticated and translated into Armenian, is required. [40] Indonesia requires the collection of a residential identity number, driving licence or passport number for residents, as well as a beneficial owner’s tax ID or other similar tax ID number. [41] Finally, Brunei Darussalam requires an identity card number or passport number. [42]

Box 7. Assigning beneficial owners unique register identifiers in the United States

In the United States (US), individuals may electronically apply for a unique identifier that is assigned for sole use in the Beneficial Ownership Information System, the national BO registrar administered by the Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (FinCEN). To receive a FinCEN identifier, an individual must provide their name, date of birth, address, and unique identifying number and its issuing jurisdiction from an acceptable identification document, along with an image of the document. These are the same requirements for reporting companies submitting BO declarations. Once a beneficial owner or company applicant has obtained a FinCEN identifier, reporting companies may report this in place of the otherwise required four pieces of personal information. Companies may also request a FinCEN identifier when they submit a BO declaration by checking a box on the reporting form. [43]

Identifying legal vehicles

While registrars of BO information typically carry the primary responsibility for verifying the identity of beneficial owners, company registrars often play the most pivotal role in identifying companies. They issue reliable identifiers and collect documents as part of the business registration process, and they gather and hold other information about companies, such as their registered address and the sector in which they operate. Moreover, company registers maintain information about individuals who are operating a company. While this is most commonly directors, it can also include shareholders and others who are beneficial owners. [44] Other legal vehicles, such as trusts, may or may not be registered with an authority such as a tax agency, as in the UK, or Master of the High Court, as in South Africa and Namibia.

As with natural persons, relying simply on the name of a legal vehicle is insufficient for confident identification. This challenge is primarily tackled by registrars collecting and using reliable identifiers that are issued by a known authoritative source like a company register or tax authority, along with information about that source. Where company registrars are also responsible for collecting BO information, they may already be the issuing authorities of company registration numbers or of Legal Entity Identifiers (LEI). If they collect BO information at the same time as issuing those numbers for newly formed entities, uniquely identifying companies is less challenging.

To be reliable, identifiers should be:

- unique to a legal vehicle within the given identifier scheme, and the only identifier that the legal vehicle has within that scheme;

- persistent, such that it is the only identifier referencing a legal vehicle historically and into the future, even if it is dissolved;

- resolvable, such that there is a mechanism for using it to check that the related company exists with the authoritative-issuing source. [45]

Where possible, the same reliable identifiers should be used by the BO and other government registers, as it allows information to be brought together for the purposes of verification. For example, information on shareholders held by the company register can be cross-checked to help verify the interests and beneficial owners reported in a BO declaration. In theory, where it is up to date and well structured, shareholder information could even be used to complete a declaration by automatically identifying shareholders who qualify as reportable beneficial owners, rather than requiring information on shareholders to be reported to the BO register again.

Examples of reliable identifiers include those issued by governments, like authoritative legal entity identifiers and tax ID numbers, as well as those issued by well-used international identifier schemes, such as Global Legal Entity Identifiers (Box 8). [46] Examples of other information that can serve as identification attributes for legal vehicles include date of incorporation, jurisdiction of incorporation or registration, registered address, and other contact information.

Box 8. International Organization for Standardization’s Legal Entity Identifiers

The International Organization for Standardization (ISO) 17442-1:2020, Financial Services – Legal Entity Identifier is an example of a well-used international identifier scheme. [47] The LEI is a global, 20-character, alphanumeric identifier standard that uniquely and unambiguously identifies a legal entity. It is managed by the Global Legal Entity Identifier Foundation (GLEIF). GLEIF was established by the Financial Stability Board (FSB), an international body that monitors and makes recommendations about the global financial system. [48]

A 2019 peer review by the FSB found that LEI codes have been issued for legal entities incorporated in more than 220 countries. [49] However, more than 50% of the jurisdictions have less than 100 codes issued, and uptake has been highest in Canada and the EU. The LEI system is based on a cost-recovery model, meaning the costs associated with obtaining and renewing an LEI cover the administrative expenses associated with the LEI system. While the LEI codes and reference data may be used free of charge, entities must pay a fee to local operating units to register and renew the LEI assigned to them. [50]

LEI records include sufficient details to disambiguate and identify legal vehicles as part of their level one data on “Who is Who”, including:

- the official name of the legal entity, as recorded in the official registers;

- the registered address of that legal entity;

- the country of formation;

- the codes for the representation of names of countries and their subdivisions;

- the date of the first LEI assignment; the date on which the legal entity was first established; the date of last update of the LEI information; and the date of expiry, if applicable. [51]

Furthermore, GLEIF has worked on certifying a number of mappings which facilitate the connection of data about organisations, market listings, their securities, and their bank accounts, using their LEIs. [52] For example, one mapping allows data users to rely on the LEI to link an entity to its securities, which have an International Securities Identification Numbering (ISIN) code, as defined in the ISO 6166 standard. [53] LEI data has also been republished in line with the Beneficial Ownership Data Standard (BODS) to help all parties looking to make sense of global corporate ownership chains, even if further investigation or additional data will be required to seek out information on the ultimate beneficial owners. [54]

Understanding relationships between individuals and legal vehicles

BOT seeks to understand the direct and indirect relationships that exist in a network of related legal vehicles, individuals, and, in many cases, other assets. [55] To accurately and precisely capture the relationships between individuals and legal vehicles in these BO networks contained in one or more BO declarations, registrars need to collect sufficiently detailed information about the interests that establish the BO relationships being reported. As with all BO information, this should be done in a structured way, allowing the registrar and data users to understand these relationships and use the information effectively. [56] Information about the relationship may need to be verified, for example through retrieval or cross-referencing of existing information, or review of supporting documentation (see Box 2).

A BO disclosure regime must therefore define the information fields and structures needed to describe relationships between natural persons and legal vehicles involved in declarations. At a minimum, the information must establish a link between a beneficial owner and the declaring legal vehicle that is the subject of a particular disclosure. The interests that constitute this link can be direct or indirect.

While the information disclosed about relationships between parties will depend on the disclosure regime, there are two main areas where the level of detail must be defined. First is the level of detail required on direct interests through which ownership or control is exerted. A direct interest is typically based on immediate (legal) ownership, financial benefit, or means of control, without any intermediary or indirect connection involved. This includes describing:

- the types of interests held that create a BO relationship, for example, control interests, ownership interests, or both;

- specific means of ownership, for example, shareholding over the statutory reporting threshold, and ways individuals can derive economic benefits as defined in legislation, e.g. having rights to profits;

- specific means of control, as defined in legislation, for example, the right to appoint or remove directors or to approve or amend the business plan;

- the level of interest where relevant, for example, the exact percentage of shareholding;

- when the ownership or control relationship begins and ends.

Second is the level of detail required about indirect relationships in the chain of ownership between the declaring company and the beneficial owner. Indirect relationships can be held through various types of intermediaries or arrangements, such as trusts, companies, or agreements. The detail reported can range from disclosing only the beneficial owner, to disclosing every intermediate arrangement, legal vehicle, and interest in the entire BO network of direct relationships as structured data.

Jurisdictions should collect some information on intermediaries where BO is held indirectly. Many jurisdictions do not, so users of the information cannot know if BO is held directly or indirectly, or whether any intermediaries exist; this also makes combining data more challenging (see Box 9). Where shareholder information is available to users, it can help fill in the gaps – yet often it is not structured, sufficiently detailed, or up to date. As a minimum, registrars could require declaring companies to disclose information on how the beneficial owner’s relationship to the declaring company relates to its legal ownership.

Balancing the level of detail on interests

Registrars must find a balance in the level of abstraction at which to gather and then share information about interests. On the one hand, ownership and control information should not be structured at such a high level of abstraction that it obfuscates details about the interests that create the relationship and makes them more difficult to verify. Yet on the other hand, given differences in their legal frameworks, connecting information from BO registers in different jurisdictions may require a higher level of abstraction in order to combine it. Ensuring data is interoperable – that is, able to be readily used with other sources and integrated into different systems and processes – requires the right level of detail. While this is also a key consideration for other information fields, it is most critical for interests.

For example, a beneficial owner falls into one of several categories defined by law: (a) Owning directly or indirectly at least 25% of the voting rights, voting shares, or capital of the reporting entity. Simply capturing that a beneficial owner falls into this category in an information field (e.g. reporting “category (a)”) would obfuscate many details. In this instance, implementers should also capture information on:

- whether the interest is direct or indirect (and if the latter, potentially include additional details);

- what class(es) of shares are held and what interests (i.e. voting rights, voting shares, or capital) are associated with these;

- the exact percentage of each class of the reported shares held;

- when the ownership relationship began and, if relevant, ended.

To illustrate, the UK People with Significant Control (PSC) register does not collect information on whether the interests are direct or indirect. When the interest involves share ownership, the register does not collect information as an absolute value, but rather as a band (i.e. 25–50%; 50–75%, or 75–100%). [57] This is insufficient detail to understand how BO is held – what the FATF refers to as the “status” of the beneficial owner. [58]

Failing to have sufficient detail on interests raises barriers to:

- verification, as it is not possible to establish whether different declarations contradict each other, or whether more than 100% have been declared in all cases;

- use, as it is not possible to understand full BO networks if there is no information on whether interests are direct or indirect;

- interoperability, as it may be difficult to combine data with a jurisdiction that collects information on ownership as an absolute number.

Box 9 highlights that it is beneficial to standardise the level of detail collected on interests. There will be differences in company legislation between jurisdictions and, therefore, different types of interests that can be held, so a common standard to which different interests can be mapped will help combine the information and make it understandable. BODS includes modelling on interests that can be applied to different jurisdictions in order to ensure sufficient information is collected to be able to understand how interests and relationships link across borders. [59]

Box 9. The challenge of making data about interests interoperable in the European Union

Challenges related to the interoperability of information on interests has been highlighted by the Deputy head of the Legal Department of the Latvian BO Register:

"[…] if the EU [Fifth AML Directive] was meant to harmonise the legal frameworks for BOT throughout the EU, and the criteria for determining beneficial ownership are identical in Member States, why does the Latvian BO register require the submission of documentary evidence about a beneficial owner who is already registered in the register of another member state? […] There is no uniform approach to the registration of a beneficial owner’s status in member states. For example, if a natural person indirectly owns 40% of the capital shares, in some countries the aspect of voting rights and property ownership are viewed as one whole (registered status: ownership rights). In others, these statuses are separated. For example, in Germany, although direct and indirect control registration is provided for, it does not oblige the beneficial owner to declare in what way the control is directly implemented. Therefore, if a natural person owns 100% of the capital shares or voting rights in the legal entity, then, despite the fact of registration, it is not possible to determine in all cases whether the control is exercised directly or indirectly. […] No less important is the fact that not all Member States register information about the persons through whom the real beneficiaries exercise control over the legal entity. […] Therefore, the Latvian BO register does not rely on the information from BO registers of other member states, but evaluates the submitted information and documents independently. The Latvian BO register does not doubt that a member state should be able to rely on information registered by the authorities of another member state, but to implement this, all member states must have the same identification and registration mechanisms, which unfortunately do not currently exist." [60]

Capturing indirect beneficial ownership relationships

BOT involves understanding when and how indirect BO relationships exist, which allows registrars and users to build pictures of complete BO networks. There are a number of ways to collect sufficiently detailed information to build such pictures. As with all details collected, the right approach will depend on the information already available.

However, there are a range of specific challenges to collecting information about full BO networks that will be part of every declaration, particularly where these include indirect BO relationships and multiple intermediaries, including:

- multiple declaring parties in the same network disclosing the same information;

- high compliance burdens for multiple entities within a network that are covered multiple times in other declarations and subject to their own declaration;

- designing declaration forms that collect useful information about intermediaries.

Moreover, BO definitions can differ by type of legal vehicle or asset, and some definitions capture BO relationships that occur higher up the ownership chain than others. This means that information collected about related legal vehicles may overlap and conflict. For example, the beneficial owners of a trust may include any beneficial owners of a company that is party to the trust. In this case, a BO declaration for the trust and a BO declaration for the company will each report overlapping information about the same natural persons.

To avoid duplication, rather than collecting information on full BO networks in each BO declaration, it may be preferable to combine information from multiple sources. This can be done by:

- making use of existing information on direct relationships;

- collecting information on elements of a BO network rather than entire ownership chains as part of BO declarations; and

- combining these to understand full networks.

This and other approaches are discussed in more detail below.

Approaches to understanding full beneficial ownership networks

There are different considerations when deciding which approach to use when collecting sufficient detail from a declaring company in order to understand their BO network. The following section outlines four approaches and explores their advantages and disadvantages. These approaches are examples and are not mutually exclusive, as elements from different approaches can be combined. It will be essential for the registrar to provide guidance to help those obliged to make declarations comply with any approach.

Full network disclosure

In Armenia, all legal vehicles – including those that may be related – are required to declare information on all intermediaries between the declaration subject and the beneficial owner, including any foreign entities and arrangements. This is called the full network disclosure approach. The advantage of this approach is that it is comprehensive, and also covers foreign companies. However, there is considerable redundancy of information, as multiple declarations may cover the same individuals, legal vehicles, and interests. These may conflict and need to be reconciled, which can be a challenge and cost additional resources. Information on foreign companies is particularly difficult to verify. In addition, this is the approach with the highest compliance burden for declaration subjects.

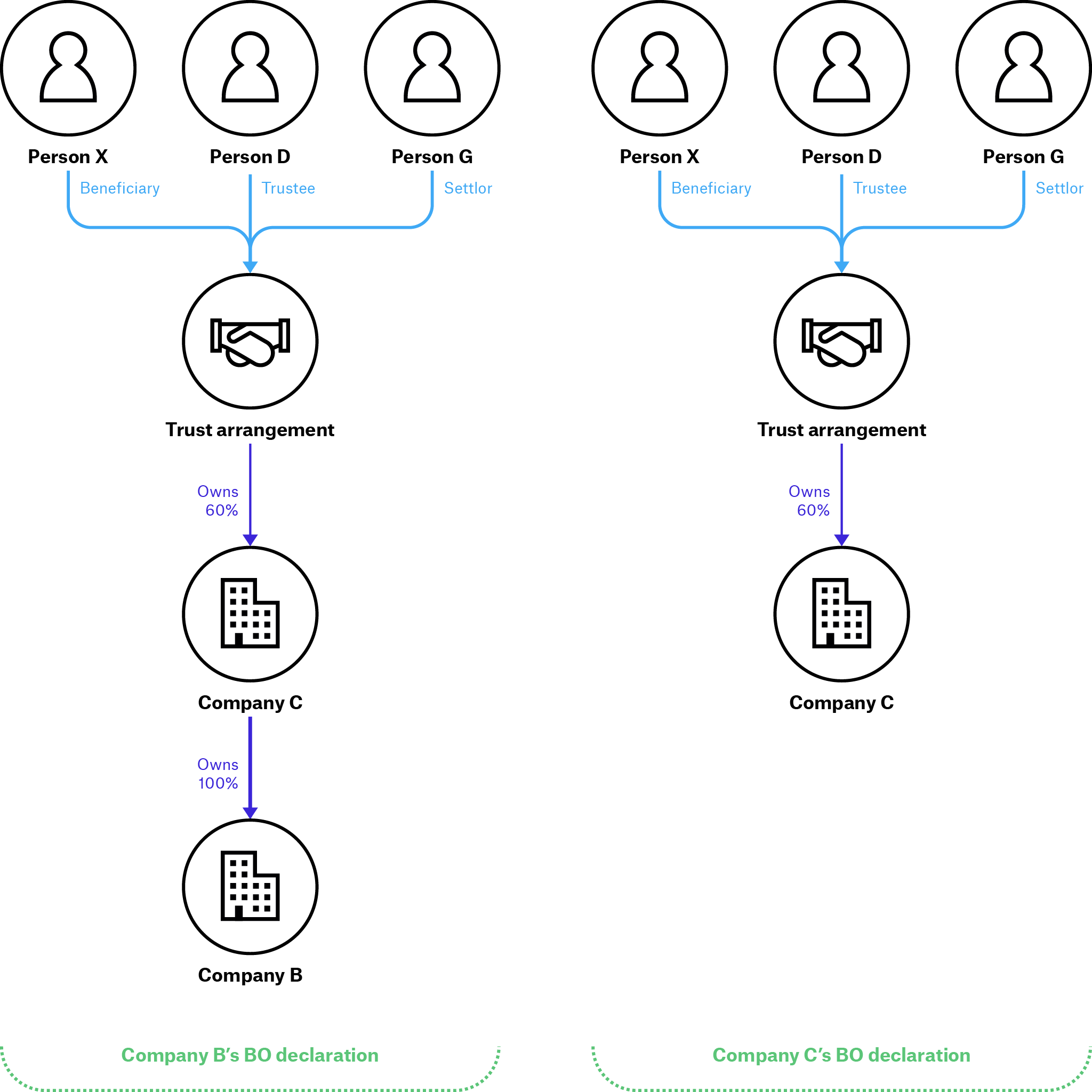

Figure 2. Illustrative example of the full network disclosure approach

In this example, all legal vehicles are assumed to be registered in the same jurisdiction. Both Company B and C will disclose information on Company C, the Trust arrangement, and Person X, Person G and Person D. The latter three parties will need information from Company B and Company C each time a declaration is filed (e.g. annually), and they will need to notify both entities if there is a change in the BO network that needs to be reported. Additionally, Person D might be obliged to disclose details of those with roles in the Trust arrangement to a register of trusts.

Relevant legal entities

In the relevant legal entities approach, information on a legal entity can be provided in a BO declaration where:

- the legal entity holds a direct interest in the legal vehicle that is the subject of a BO declaration that would qualify it as a beneficial owner if it were an individual (e.g. shareholding of over 25%); and

- the legal entity is domestically registered and therefore subject to the same disclosure requirements.

This approach is taken by the UK, where the qualifying entity holding a direct interest is called the relevant legal entity (RLE). The person making the declaration does not have to provide additional information on potential indirect BO interests held via the RLE, as the information is already assumed to exist.

The advantages of this approach are that it allows better visibility of BO networks than when only beneficial owners are declared. It also lowers the compliance burden, as many companies will only have to disclose information about their direct owners and not about indirect relationships. Finally, there is less redundancy of information on beneficial owners, as different intermediaries do not have to declare the same beneficial owner.

However, there are several disadvantages of this approach. First, it is largely limited to domestic legal vehicles, as it counts on the fact that the existing RLE will have made a BO declaration domestically. It also only provides information on some legal vehicles in the network since only those that would qualify as a beneficial owner were they an individual are covered. This means that if a natural person at the top of a network is a beneficial owner via control interests held through an entity that did not meet this criteria, the intermediary in the relationship would be missing. Moreover, it is potentially easier to avoid disclosure unless a register conducts very good verification checks, as reporting an RLE rather than reporting nothing may look less suspicious. In the UK, the listing of an RLE that is not eligible is not uncommon. It is possible that this is not intentional and that the guidance is not clear enough. Finally, while lower redundancy is an advantage of this approach, it removes opportunities to verify different declarations against each other for consistency.

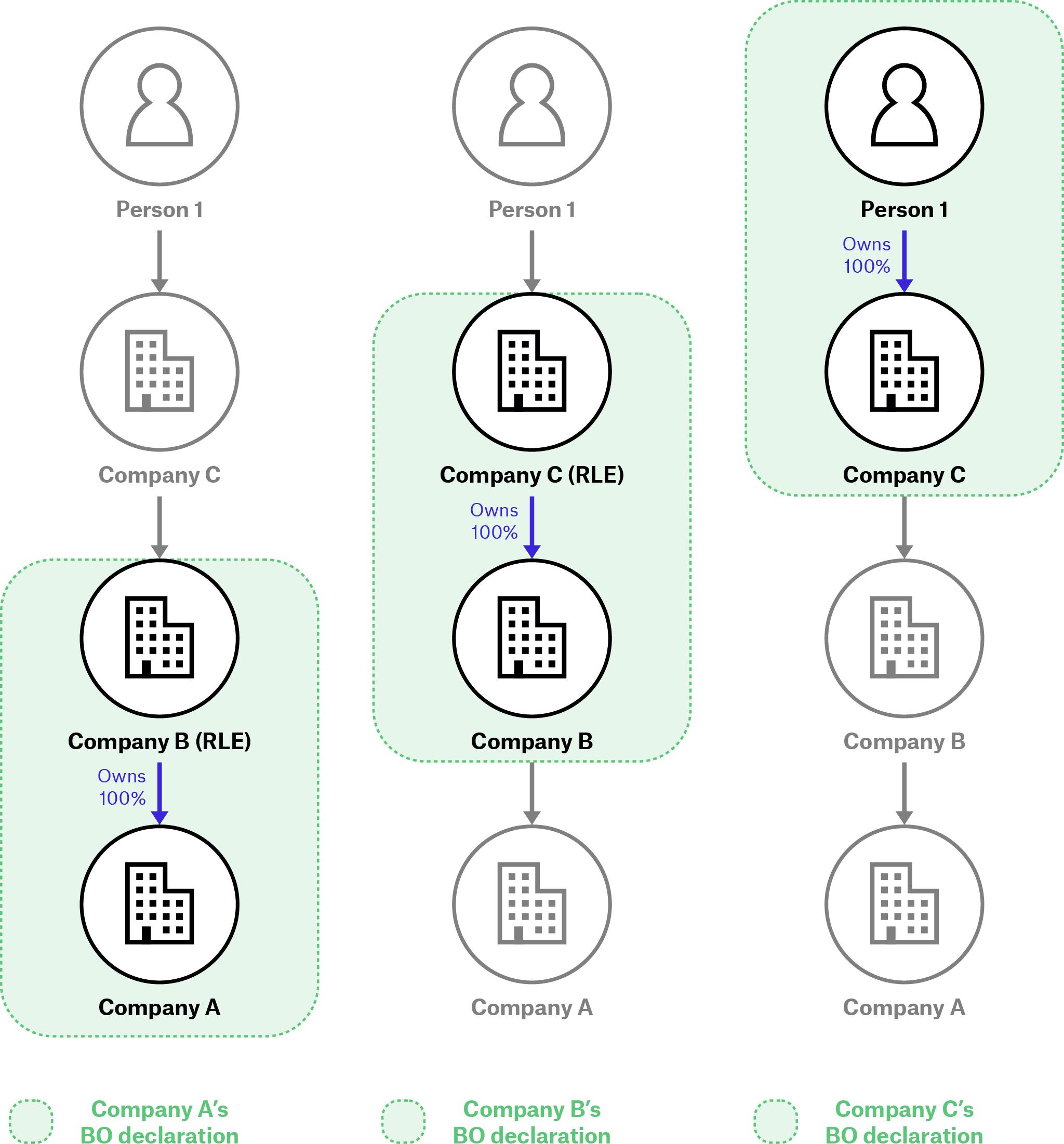

Figure 3. Illustrative example of the relevant legal entity approach

In this example, Company B owns 100% of the shares in Company A, and is a domestic entity. Company A therefore registers Company B as an RLE when making a BO declaration. Company A is not required to look further up its chain of ownership for any indirect interests held via Company B, as these do not need to be reported. Company C is also a domestic company, and its details will be entered as an RLE on Company B’s BO declaration. The ultimate beneficial owner, Person 1, is only required to be reported through Company C’s BO declaration. Source: Reproduced from UK PSC Guidance. [61]

Beneficial owners and direct-interest holders

South Africa uses the beneficial owners and direct-interest holders approach. This involves collecting information as part of a BO declaration on all beneficial owners and on all the legal vehicles through which they hold beneficial ownership that have a direct interest in the declaring entity. The advantages here are similar to the RLE approach. However, this approach is potentially more comprehensive since, unlike the RLE, it always includes the disclosure of all beneficial owners and it does not exempt any direct-interest holders involved in a BO relationship with the declaring legal vehicle.

The disadvantages of this approach are a lack of visibility when part of the network is abroad and of legal vehicles that are direct-interest holders but not linked to beneficial owners. There is also some redundancy in the information collected on beneficial owners of domestic legal vehicles. On the other hand, redundant information can also be retrieved and used for verification cross-checks, though the information collected may be insufficient and not up-to-date enough to pre-populate declaration forms. Implementers would also need to consider how to handle multiple legal vehicles providing information on the same beneficial owners at different points in time. These may conflict, and the timeliness of the declarations has the potential to cause issues when using the information as part of verification processes.

This approach could also be combined with a requirement to provide more information if a legal vehicle holding a direct interest is abroad. For example, if a foreign company that is a direct-interest holder in the BO network is not the final intermediary before the declaring company’s beneficial owner(s), the declaring company could be required to provide additional information on intermediaries and intermediary relationships at each level up to the beneficial owners, or at the very minimum for those intermediaries who sit on the ultimate level before the beneficial owners.

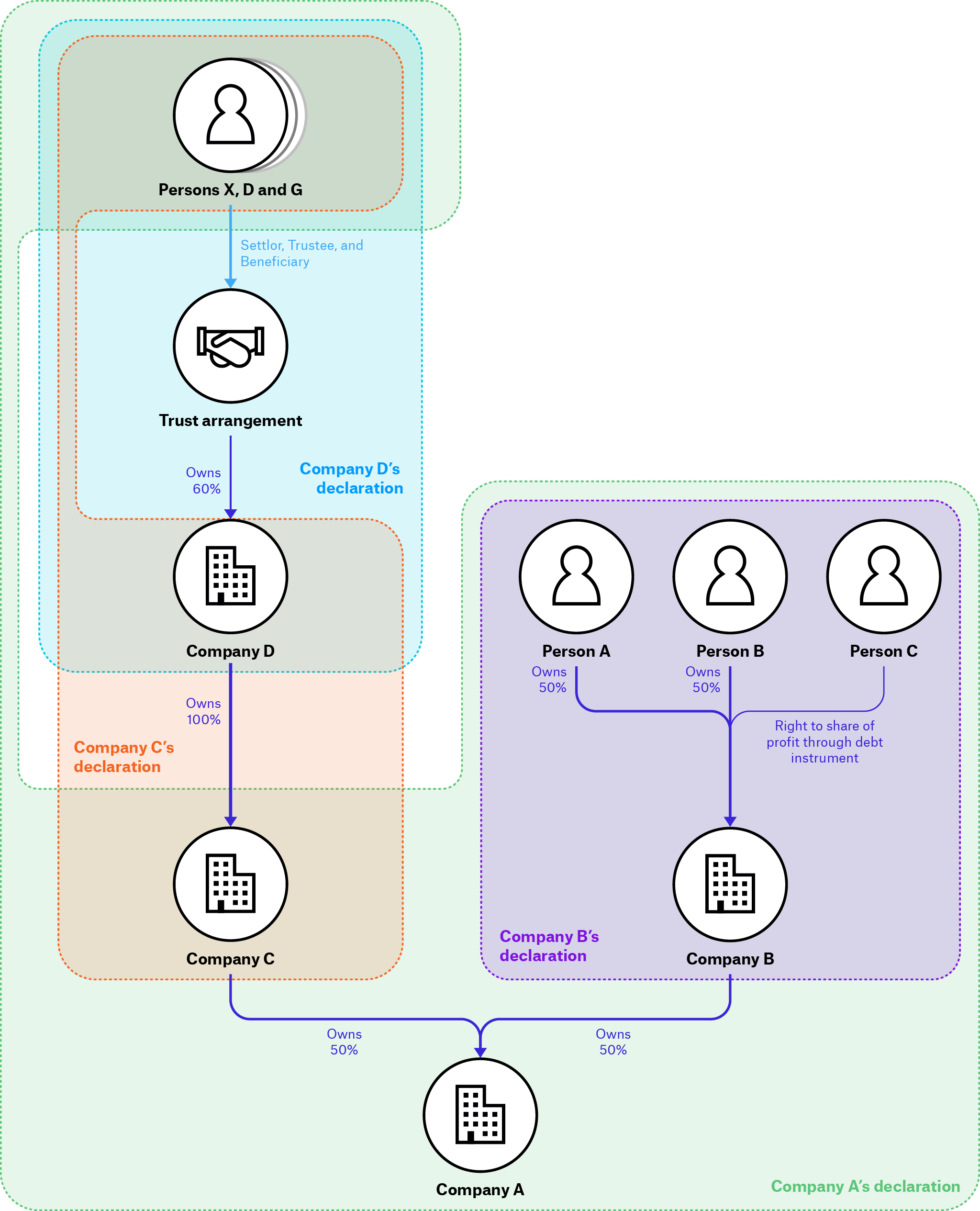

Figure 4. Illustrative example of the declaring beneficial owners and direct-interest holders approach

In this example, each shaded area represents information collected in one BO declaration. Company A will report its two direct-interest holders, Company B and Company C, along with its beneficial owners, Persons A, B, C, D, G, and X (green area). Information on other intermediaries, such as Company D and the Trust arrangement, would be captured in a separate BO declaration for Company D (blue area).

All legal vehicles are assumed to be registered in the same jurisdiction and therefore equivalent BO declarations for company B, C and D are available in the BO register. However, if the companies were non-domestic, the ownership visibility would be as follows:

- If Company B is non-domestic: Same visibility, covered by Company A’s declaration.

- If Company C and D are non-domestic: Lost visibility on Company C and Trust arrangement.

- If Company D is non-domestic: Lost visibility on Trust arrangement.

Aggregating direct interests

In the aggregating direct interests approach, comprehensive information on direct interests is used to understand full ownership networks. Each declaring entity discloses information on the beneficial owners and the entities, arrangements, and individuals who have a direct interest in the declaring company. The declared information is combined with other types of information to build out the BO networks, including shareholder information, information on parties to a trust, and information on nominee relationships.

This approach could arguably be the most effective. It relies on accurate, well-structured, and up-to-date information being available in other registers (particularly shareholder, trust, and nominee registers). The main advantage is that it can greatly improve and enable compliance, especially if existing information is used to pre-populate declaration forms, and that certain BO relationships may simply need to be confirmed to be accurate. If a shareholder register has a constitutive effect, whereby the act of registration confers certainty over the legal rights associated with shareholdership, the information is likely to be accurate. It could then be contemplated that many BO relationships could be exempt from disclosure because they are already captured in the shareholder register, lowering the compliance burden further. Less information is required to be disclosed compared to the full network disclosure approach, which means there is less redundancy and a lower compliance burden, and it is more comprehensive than the RLE approach. Information on direct interests can also be used to verify BO declarations, and any changes are easier to track.

The main disadvantage with this approach is that it is limited to domestic interests. Although declaring entities would give information about the first level abroad, they would not provide any information on additional layers until information on direct interests was being shared at scale internationally. The barrier for sharing information on direct interests may be lower than for BO information. Another drawback is that it is limited to pre-populating fields for types of ownership and control captured in shareholder registers, which does not cover the full scope of interests contemplated as part of BO disclosures.

Future developments, including an expected increase in the implementation of nominee registers or nominee disclosures to company or BO registers, as well as improvements to asset registers, make it reasonable to assume many relevant interests will start to be captured via these mechanisms. However, separate disclosure requirements may still be required as part of BO declarations where BO is not exercised through the holding of shares, and where it is held through foreign legal vehicles.

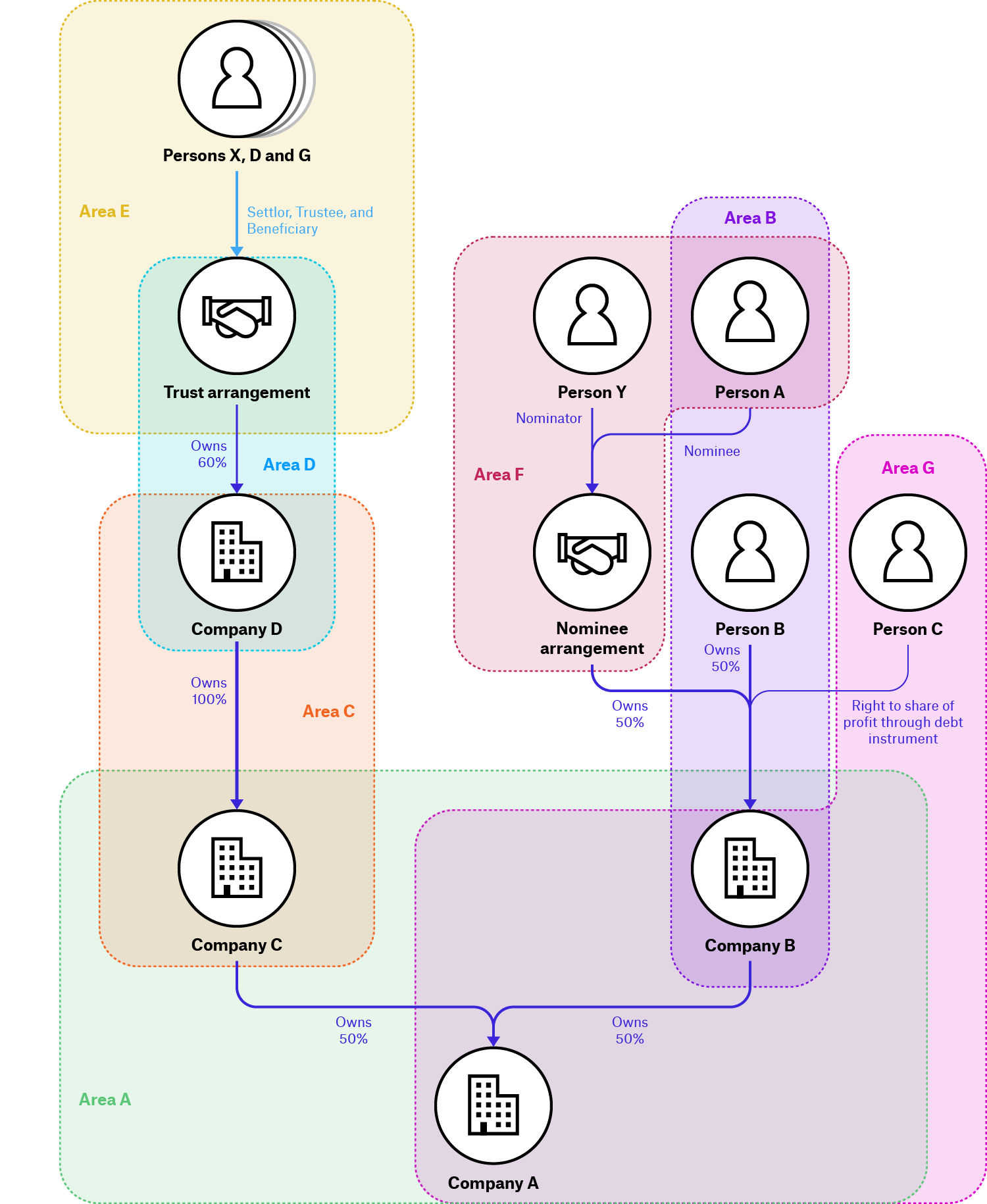

Figure 5. Illustrative example of the aggregating direct interests approach

In this example, information on direct interests from different sources is combined to create a full ownership network. Combining information relies on having sufficient detail to identify each legal vehicle and individual, as discussed above, and to link these across datasets (e.g. reliable identifiers). In this visualisation, the different areas represent information held in nominee, trust, or shareholder registers on each legal vehicle, and complementary information collected through BO declarations. The information from other registers is used pre-populate fields in BO declarations:

- Areas A, B, C, and D (green, purple, orange, and blue): Information from a central shareholder register.

- Area E (yellow): Information from a central trust register.

- Area F (red): Information from a central nominee register.

- Area G (pink): Additional information from Company A and Company B’s BO declarations to a central register, complementing the information already held in other registers that is used to prepopulate Company A and Company B’s respective declarations.

Ensuring beneficial ownership data is auditable and usable

Policy impact from BOT reforms is generated by actors using BO information to answer their questions and reach actionable insights. Examples of users include government agencies like procurement authorities, law enforcement, civil society, academic researchers, obliged entities, and other private-sector actors. Whether individuals use BO information to help manage business risks, investigate tax evasion, or improve public procurement, the different questions BO data users seek to answer determine user needs, or the specific requirements they have to effectively use BO information.

For example, being able to identify a beneficial owner by name may be more important to a user who is asking a asking a qualitative question (e.g. who is the beneficial owner of a specific company in my supply chain) than to a user asking a quantitative question (e.g. how many companies in my jurisdiction have beneficial owners who are domestically registered taxpayers). Despite these differences, many user needs overlap. Three key needs shared among many users that relate to the level of detail in BO information include:

- the ability to understand relationships between individuals, legal vehicles, and assets within and across BO and other information sources;

- a baseline level of data accuracy to foster confidence in conclusions they reach when using the information;

- basic quality features, such as having structured data that is regularly updated and allows full visibility of any changes that occur over time. [62]

These needs can largely be met by ensuring the registrar is performing its first two core functions of gathering enough information to identify beneficial owners and legal vehicles, and understanding relationships between them. However, to ensure the information acquired is fully auditable and usable, the registrar should also capture details about:

- changes over time to ensure that BO disclosures are auditable by data users and access to the register as a safeguard against misuse;

- the person making a declaration, such that they are also identifiable;

- attributes relevant to the policy aim, such as specific information fields that are identified as important through user research.

Box 10. Lessons learned from the United Kingdom People with Significant Control register [63]

Open Ownership and the Tax Justice Network assessed information from the UK PSC register, which has been in BODS format since August 2022. It yielded several insights on policy issues, anomalous patterns, and complex ownership structures identifiable within the data. [64] The dataset covered 5.9 million natural persons, 6.1 million legal vehicles, and 16.6 million ownership or control interests.

The most common scenario involved a beneficial owner holding shares, voting rights, and board appointment rights together, indicating high levels of control by single beneficial owners. Shareholding emerged as the most prevalent type of interest, with 98% of the beneficial owners holding multiple interests in a single entity through this type of ownership; however, some beneficial owners hold significant influence or control without shareholding, which may indicate either legitimate governance structures or gaps in reporting requirements. Certain entities also exhibited extreme ownership patterns. Most entities had between one and four beneficial owners. However in rare instances, ownership structures became highly complex with up to 34 beneficial owners. In four outlier cases, a single beneficial owner was linked to over 1,000 entities.

At the same time, the assessment highlighted key challenges in auditing and using BO data, particularly regarding the level of detail. It also pointed to best practices for improving data usability. Below are three major challenges identified, along with strategies to address them.

Challenge 1: Entity resolution for persons and entities

Entity resolution is the process of establishing whether multiple records about an individual or legal vehicle are referring to the same or to different individuals or legal vehicles. The PSC data contained multiple records for the same person or entity due to changes in relationships (e.g. shareholding changes) or registration updates (e.g. address changes). These patterns are common across BO datasets. Leveraging Companies House identifiers for entities and autogenerated person identifiers from Open Ownership’s BODS-formatted UK PSC data enabled effective deduplication. [65] This resulted in a 10% reduction in entity records and a 5% reduction in person records, improving data clarity.

Challenge 2: Interpreting ownership interests with range-based values

As noted earlier, ownership and voting rights in the UK PSC are recorded in broad ranges (25–50%, 50–75%, 75–100%) rather than as precise percentages, limiting granular analysis. This makes it difficult to identify the most common or least frequent ownership and control percentages, hindering the detection of distribution patterns. It also restricts calculations such as determining exact percentage differences between beneficial owners of the same entity, a useful metric for assessing disproportionate control. While exact share distributions cannot be determined, alternative methods such as frequentist analysis can still provide insights by identifying the most commonly reported percentage ranges across different types of interests.

Challenge 3: Managing outdated information

The dataset includes historical records, such as ended relationships, which is good practice but can lead to misrepresentation of the information in current analyses and increase computational load. Filtering out ended relationships can significantly reduce dataset size while ensuring an assessment reflects the present state of ownership. In this case, removing ended relationships reduced ownership links by 10%.

These insights from the UK PSC register underscore the importance of reliable identifiers for accurate entity and person matching, precise ownership values for detailed interest analysis, and historical data management to ensure relevance and reliability when working with BO data.

Change over time and access

Keeping up-to-date and historical BO records underpins any transparency initiative around ownership and control, and many registers require the timely reporting of changes to BO. Just as crucial is ensuring those records are easy to access, interpret, and check – that is, that they are auditable. [66] Therefore, a key piece of information to collect is the date and time a declaration was made or modified.

As mentioned earlier, a record of BO can be seen as a ledger of information that builds up over time. New information about the ownership and control of a legal vehicle supersedes older information. It includes changes, such as the sale of shares, company rules being updated, and new companies being incorporated. Broadly, dates and times in BO registers help users understand:

- when a BO interest existed;

- when details of that interest were reported;

- when the information was added to the register, both at the initial point of submission and through any subsequent changes.

Registers should capture dates of changes and format these in line with internationally recognised standards, such as ISO 8601. [67] This forms part of a well-designed BO declaration and storage system. It can then be shared as necessary. [68]

In addition, registrars may need to collect information about who has accessed BO information in a register as a safeguard in the event it is misused. [69] For example, where access is layered with stratified permissions for certain users (such as law enforcement) to access more sensitive information, a log of who has viewed this information should be recorded within the register. It is in turn critical that access to internal records about who has viewed a BO declaration is strictly limited to authorised registrar staff. This helps to protect actors – such as journalists and others who may be using the data for sensitive purposes – from retaliation. [70]

The person making a declaration

Declarations about BO are often made by a person who is not the beneficial owner. It is good practice to require a means of verifying the identity of the person submitting a BO declaration as an additional check to reduce the risk of and improve accountability for false or inaccurate submissions. This could include collecting specific information fields about individuals making a declaration (Box 11).

The information that it is necessary to collect from those submitting a declaration depends on both the level of assurance desired and any requirements that are in place for legal recognition and oversight. Examples include registration with an AML register and physical presence in the jurisdiction at a registered residential or business address. The level of identity checks may reasonably be lower than for the declared beneficial owners, especially when there are strong oversight mechanisms. However, when those submitting declarations are relied on heavily for third-party verification checks, a level of assurance more commensurate with that for beneficial owners may be appropriate.

Box 11. Verification of individuals submitting a declaration

Jurisdictions such as Armenia, Austria, Czech Republic, Italy, Japan, Panama, and Spain require an authorised declaring person to disclose and certify the accuracy of the BO information submitted to a register. This can be a beneficial owner, a company advisor (such as a lawyer, auditor, or consultant), or a notary. In certain countries, it is a requirement for notaries, lawyers, or accountants considered obliged entities under the AML framework to be involved in the incorporation of legal entities or any changes of ownership. [71]

In the EU, at least 12 member states take steps to verify the identity of individuals making BO declarations, although requirements to do so are not always present in law. Many of the approaches require declarations to be submitted by a domestically regulated party to ensure there is a responsible representative based in the jurisdiction. [72] However, only around five EU member states require supporting information for the people submitting BO declarations.

For example, in Croatia, a copy of an identification document is required for the person submitting the declaration. In Denmark, users submitting a declaration login with their MitID and must either be registered with the Danish Business Authority and digitally sign their application, or, where a declaration is submitted by a professional third party, this party must confirm their registration in the AML register. [73]

Attributes relevant to policy aims

Finally, a jurisdiction’s policy aims may require specific information to be gathered in BO declarations. As discussed above, whether it is possible to retrieve this information or whether it must be collected depends on the broader approach to implementation, such as the agency in which the registrar is based. For example:

- where BO information will be used for tax enforcement, registrars should ensure they have tax IDs as part of declarations, for example, by connecting declarations to a taxpayer register to retrieve a tax ID using a data field such as a national ID number;

- where there is a need for users to be able to conduct analyses on specific sectors, for example, for environmental or anti-competitiveness regulations, acquiring information on a company’s sector could be done by retrieving it from a business register using a company identifier data field;

- jurisdictions implementing BOT as part of their commitments under the Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative could fulfil the requirement to publish information about a person’s status as a PEP by acquiring information from a PEP register, or collecting it directly. [74]

User research is essential to identifying attributes that should be included in BO declarations, and it should start at the beginning of the process of developing a register, including before finalising legislation. User research ensures a BO register is effective, user friendly, compliant with necessary standards, and ultimately meets the policy aims a jurisdiction sets out to achieve. [75]

Footnotes

[29] Tymon Kiepe, Verification of beneficial ownership data (Open Ownership, 2020), https://www.openownership.org/en/publications/verification-of-beneficial-ownership-data/.

[30] Kadie Armstrong and Stephen Abbott Pugh, Using reliable identifiers for corporate vehicles in beneficial ownership data (EITI and Open Ownership, 2023), https://www.openownership.org/en/publications/using-reliable-identifiers-for-corporate-vehicles-in-beneficial-ownership-data/.

[31] The Rebel Accountant (anon.), Taxtopia: How I Discovered the Injustices, Scams and Guilty Secrets of the Tax Evasion Game (Octopus Publishing Ltd., 2023), 179.

[32] For example, see: Janet Hughes, “What is identity assurance?”, Government Digital Service (UK government blog), 23 January 2014, https://gds.blog.gov.uk/2014/01/23/what-is-identity-assurance/.

[33] See this guide created by the World Bank Group’s Identification for Development (ID4D) Initiative: ID4D, “Part III: Topics – Levels of assurance (LOAs)”, in Practitioner’s Guide (World Bank, 2019), https://id4d.worldbank.org/guide/levels-assurance-loas.

[34] FATF, Guidance on Beneficial Ownership of Legal Persons (FATF, 2023), 24, https://www.fatf-gafi.org/content/dam/fatf-gafi/guidance/Guidance-Beneficial-Ownership-Legal-Persons.pdf.coredownload.pdf.

[35] FATF, Guidance on Beneficial Ownership of Legal Persons, 24.

[36] Lord and Kiepe, “Operationalising structured beneficial ownership data” in Structured and interoperable beneficial ownership data, https://www.openownership.org/en/publications/structured-and-interoperable-beneficial-ownership-data/operationalising-structured-beneficial-ownership-data/.

[37] Louise Russell-Prywata, NEBOT Paper 2 – Verification and Quality of Beneficial Ownership Information in the EU (European Commission, Directorate-General for Financial Stability, Financial Services and Capital Markets Union – Publications Office of the European Union, 2023), https://images.transparencycdn.org/images/NEBOT-Paper-2.pdf.

[38] Government of China, The People’s Bank of China, Legal Affairs Department, “中国人民银行 国家市场监督管理总局令〔2024〕第3号 (受益所 有人信息管理办法)”, Article 11, 30 April 2024, http://www.pbc.gov.cn/tiaofasi/144941/144957/5342579/index.html.

[39] Government of Malawi, Companies Act, Companies (Beneficial Owners) Regulations, 2022, Schedule Form BO1, 197, https://www.fia.gov.mw/publications/beneficial-ownership-regulation.pdf.

[40] Government of Armenia, “Օ Ր Ե Ն Ք Ը Ընդունված է 2021 թվականի հունիսի 3-ին «ԻՐԱՎԱԲԱՆԱԿԱՆ ԱՆՁԱՆՑ ՊԵՏԱԿԱՆ ԳՐԱՆՑՄԱՆ, ԻՐԱՎԱԲԱՆԱԿԱՆ ԱՆՁԱՆՑ ԱՌԱՆՁՆԱՑՎԱԾ ՍՏՈՐԱԲԱԺԱՆՈՒՄՆԵՐԻ, ՀԻՄՆԱՐԿՆԵՐԻ ԵՎ ԱՆՀԱՏ ՁԵՌՆԱՐԿԱՏԵՐԵՐԻ ՊԵՏԱԿԱՆ ՀԱՇՎԱՌՄԱՆ ՄԱՍԻՆ» ՕՐԵՆՔՈՒՄ ՓՈՓՈԽՈՒԹՅՈՒՆՆԵՐ ԵՎ ԼՐԱՑՈՒՄՆԵՐ ԿԱՏԱՐԵԼՈՒ ՄԱՍԻՆ”, Article 60.3, 2021, https://www.arlis.am/DocumentView.aspx?DocID=153756. Note: translation from Armenian done using Google Translate.

[41] Government of Indonesia, “PERATURAN PRESIDEN REPUBLIK INDONESIA NOMOR 13 TAHUN 2018 TENTANG PENERAPAN PRINSIP MENGENALI PEMILIK MANFAAT DARI KORPORASI DALAM RANGKA PENCEGAHAN DAN PEMBERANTASAN TINDAK PIDANA PENCUCIAN UANG DAN TINDAK PIDANA PENDANAAN TERORISME”, Article 16 (2), 2018, https://jdih.setkab.go.id/PUUdoc/175456/Perpres%20Nomor%2013%20Tahun%202018.pdf.

[42] Government of Brunei Darussalam, Companies Act (Chapter 39), Companies (Register of Controllers and Nominee Directors) Rules, 2020, Part 2 – Register of Controllers, 2477, https://www.agc.gov.bn/AGC%20Images/LAWS/Gazette_PDF/2020/EN/S038.pdf.

[43] FinCEN, Small Entity Compliance Guide Version 1.1 – Beneficial Ownership Information Reporting Requirements (FinCEN, 2023), 40, https://www.fincen.gov/sites/default/files/shared/BOI_Small_Compliance_Guide_FINAL_Sept_508C.pdf.

[44] Hayley Thompson, Business Register Data for the Modern Supply Chain: 2023 Report on Data Availability in Business Registers Around the World (ECCMA, 2024), 5, 29, https://tinyurl.com/2ur6ahmj.

[45] Armstrong and Abbott Pugh, Using reliable identifiers for corporate vehicles, 6.

[46] This is the primary identifier issued by the business register to businesses at their formation, which, when formatted in accordance with ISO 8000-116, serves as the universally unique identifier for any registered business. See: Thompson, Business Register Data for the Modern Supply Chain, 11.

[47] See: “ISO 17442-1:2020”, International Organisation for Standardisation, Edition 1, 2020, https://www.iso.org/standard/78829.html.

[48] See: “About the FSB”, FSB, updated 16 October 2024, https://www.fsb.org/about/.

[49] FSB, Thematic Review on Implementation of the Legal Entity Identifier: Peer Review Report (FSB, 2019), https://www.fsb.org/wp-content/uploads/P280519-2.pdf.

[50] “Proposed Rule: Financial Data Transparency Act Joint Data Standards”, Federal Register, published for comments August 2024, https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2024/08/22/2024-18415/financial-data-transparency-act-joint-data-standards.

[51] “Access and Use LEI Data – Level 1 Data: Who is Who”, GLEIF, n.d., https://www.gleif.org/en/lei-data/access-and-use-lei-data/level-1-data-who-is-who.

[52] “LEI Data – LEI Mapping”, GLEIF, n.d., https://www.gleif.org/en/lei-data/lei-mapping.

[53] “LEI Data – Download ISIN-to-LEI Relationship Files”, GLEIF, n.d., https://www.gleif.org/en/lei-data/lei-mapping/download-isin-to-lei-relationship-files.

[54] “Beneficial Ownership Data Standard (v0.4)”, Open Ownership, n.d., https://standard.openownership.org/en/0.4.0/.

[55] “Beneficial Ownership Data Standard v0.4 – Key concepts”, Open Ownership, n.d., https://standard.openownership.org/en/0.4.0/standard/concepts.html.

[56] Further guidance is available in: Lord and Kiepe, “Operationalising structured beneficial ownership data”.

[57] Companies House – API Enumerations, PSC Descriptions, GitHub, updated 11 October 2024, https://github.com/companieshouse/api-enumerations/blob/master/psc_descriptions.yml.

[58] FATF, The FATF Recommendations, 96.

[59] Much of the effort to develop BODS has focused on modelling interests. See, for example: Lewis Spurgin, “Feature: Interest modelling #466”, Open Ownership, Data Standard, GitHub, 26 September 2022, https://github.com/openownership/data-standard/issues/327. Guidance and documentation contain best practices about collecting sufficiently detailed information on interests. See: “Beneficial Ownership Data Standard (v0.4) – Representing beneficial owners”, Open Ownership, n.d., https://standard.openownership.org/en/0.4.0/standard/modelling/repr-beneficial-ownership.html. However, ongoing work is underway to develop further insights into the representation and interoperability of interest information.

[60] Elīna Laganovska, “Tiesiskā paļāvība uz patieso labuma guvēju reģistru informāciju”, Jurista Vārds, 14 November 2023, https://juristavards.lv/doc/284224-tiesiska-palaviba-uz-patieso-labuma-guveju-registru-informaciju/. Note: translation from Latvian done using Google Translate.

[61] UK Government, Department for Business, Energy & Industrial Strategy (BEIS), Register of People with Significant Control: Guidance for People with Significant Control over Companies, Societates Europaeae, Limited Liability Partnerships and Eligible Scottish Partnerships – Version 3 (BEIS, 2017), 11, https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/5bd9e31f40f0b604e0b7828c/170623_NON-STAT_Guidance_for_PSCs_4MLD.pdf.

[62] Julie Rialet, Understanding beneficial ownership data use (Open Ownership, 2025), https://www.openownership.org/en/publications/understanding-beneficial-ownership-data-use.

[63] Maria Jofre and Andres Knobel, “Insights from the UK People with Significant Control Register”, Open Ownership, forthcoming.

[64] “UK People with significant control (PSC) Register (2024-06-07)”, Beneficial ownership data analysis tools, Open Ownership, 7 June 2024, https://bods-data.openownership.org/source/UK_PSC/; Open Ownership, “Beneficial Ownership Data Standard (v0.4)”.

[65] “Open Ownership Register”, Open Ownership, updated 29 November 2024, https://www.openownership.org/en/topics/open-ownership-register/.

[66] Other characteristics of auditability include making data available in a range of ways, including in a browsable format, a bulk format, on a per-record basis, and via an API. See: Open Ownership, “Up-to-date and historical records” in Open Ownership Principles, https://www.openownership.org/en/principles/up-to-date-and-historical-records/.

[67] “ISO 861 – Date and time format”, ISO, n.d., https://www.iso.org/iso-8601-date-and-time-format.html.

[68] Armstrong, Building an auditable record.

[69] Kiepe, “Striking a balance”

[70] For example, see: “EU reaches deal on anti-money laundering rules, ending uncertainty about how watchdogs will access information on companies’ real owners”, Transparency International, 18 January 2024, https://www.transparency.org/en/press/eu-deal-anti-money-laundering-rules-ending-uncertainty-watchdogs-access-companies-real-owners.

[71] United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC), Enhancing Beneficial Ownership Transparency: A Study of Beneficial Ownership Registration Systems (UNODC, 2023), 69, https://www.unodc.org/documents/treaties/UNCAC/COSP/session10/CAC-COSP-2023-CRP.5.pdf.

[72] Russell-Prywata, NEBOT Paper 2, 21–22.

[73] Russell-Prywata, NEBOT Paper 2, 21–22.

[74] EITI, EITI Requirements – 2.5 Beneficial ownership (EITI, 2023), https://eiti.org/eiti-requirements.

[75] Open Ownership, A guide to doing user research.