Transparency of land ownership involving trusts – Response to the UK's Department for Levelling Up, Housing and Communities’ open consultation

Response to the Department for Levelling Up, Housing and Communities’ open consultation

Open Ownership (OO) welcomes the opportunity to respond to the Department for Levelling Up, Housing and Communities’ consultation on the transparency of land ownership involving trusts. OO provides technical assistance to countries implementing beneficial ownership transparency reforms, to help generate accurate data on beneficial ownership that complies with international standards, and meets the needs of data users across government, obliged entities, the wider private sector, and civil society.

The disclosure of information on the true owners of corporate vehicles is an essential part of a well-functioning economy and society. Transparency of corporate vehicles contributes to a better-functioning financial system and economy, both globally and within domestic economies.

Since 2017, OO has worked with over 40 countries to advance implementation of beneficial ownership reforms, as well as supporting the creation of over 15 new central and sectoral registers. OO has developed the world’s leading data standard for beneficial ownership information, co-founded the international Beneficial Ownership Leadership Group, and built the world’s first transnational public beneficial ownership register.

OO’s team of policy and technical experts works on three key areas:

- Technical assistance to implement beneficial ownership transparency

- Building technology and capacity to use beneficial ownership data

- Conducting research to inform policy and its implementation

This response is informed by OO’s experience and expertise, and will therefore focus on the questions to which this bears most relevance.

Responses to questions

Question 1

Do you agree that more direct information about the ownership and control of land, including where a trust structure is involved, would help address the issues in the housing sector identified above?

A beneficial owner is a person who ultimately has the right to some share of a corporate entity’s income or assets, or the ability to control its activities. The ownership structure of companies and other corporate vehicles, like trusts, can be complicated and opaque. This means that the individuals who own, control, or benefit from an asset using corporate vehicles can remain hidden.

It is widely accepted and reflected in international standards that having beneficial ownership information which is adequate, accurate and up-to-date on both companies and trusts is essential to fighting illicit finance and corruption, and that real estate and land are at particularly high risk for money laundering.

There is significant evidence that access to this information by users outside government can help fight illicit finance and corruption. This has also been confirmed by a November 2022 judgement by the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU), and is reflected in the latest draft of the European Union’s sixth Anti-Money Laundering Directive. The substantial number of journalistic investigations enabled by the public nature of the beneficial ownership data collected by Companies House in the UK Register of Overseas Entities (ROE) also support this. Many of these have focused on cases where natural persons are declared as the beneficial owners, a number of whom are politically exposed persons, sanctioned individuals or both, or a close family member or associate. Furthermore, OO’s research with end-users of beneficial ownership information, including law enforcement, financial investigative units, and anti-corruption agencies, shows that all these government data users rely on intelligence provided by non-governmental users of beneficial ownership registers.

However, as evidenced below, there remains a significant lack of information where trust structures are involved in corporate structures. This undermines the usability and usefulness of the UK’s public beneficial ownership data as well as offering avenues for malign actors to exploit for illicit or corrupt purposes.

With respect to addressing issues in the housing sector, OO has worked with legislators in New York State, where a main policy objective for beneficial ownership transparency was to address problems in the private rented sector. These included issues for tenants where properties were owned by opaque corporate vehicles, and tenants were unable to contact their landlords regarding numerous infractions of their rights, and it was impossible to hold negligent or rogue landlords to account. With respect to the use cases of how ownership information of land in the UK can help address other issues in the housing sector, OO endorses the submissions of the responses submitted by members of the UK Anti-Corruption Coalition, and recommends the Centre for Public Data’s recent paper Who really owns land? A briefing on trusts and property data.

Question 3

What further benefits do you see from increasing the transparency of land ownership, especially where trusts are involved, and what are the risks? Please provide any evidence you may have to support your position.

The risks inherently posed by trusts due to their legal nature are extensively documented. For further details, examples, and evidence, please see OO’s three responses to consultations of the Financial Action Task Force (FATF) regarding Recommendation 25, and other OO publications on trusts.

As the consultation itself makes clear, trusts can also derive benefits from the state and be run as businesses, so many of the arguments for beneficial ownership transparency of companies also apply to trusts. In addition, trusts and companies are frequently used within the same corporate structures. Trust assets can comprise company shares, and companies can be party to trusts. Therefore, OO treats legal entities and arrangements such as trusts collectively as corporate vehicles, and encourages governments to collect and combine information on both to gain better visibility of corporate structures.

While there may be arguments to place different requirements on particular trusts, OO takes the position that there is no justification to make all trusts subject to less stringent disclosure and transparency requirements by default. OO and many other organisations have raised concerns with this lack of parity. Experience globally – including in the UK with limited partnerships – shows that applying different disclosure and transparency requirements on corporate vehicles can lead to displacement of risk and illegal conduct. Therefore, OO echoes the consultation’s premise that the “lack of open public access to trust beneficial ownership information […] represents an unacceptable gap in the government’s transparency measures”.

This notwithstanding, governments should also ensure responsible implementation by meeting its obligations to and minimise the infringement of the rights to privacy. This should be considered simultaneously with who needs access to what information to contribute to achieving stated government policy aims, as discussed in more detail below. Risks presented to specific parties to trusts on the basis of personal characteristics including age and mental capacity should be considered, and could be addressed through a protection regime, by naming a legal representative in place of the individual, or both. Governments could also explore limiting the use of data to legitimate purposes through a licence or fair use policy, and ensuring those who face disproportionate risks can have information suppressed from broader access. Protection regimes can be crucial to stop people being exposed to disproportionate risks. The government should conduct and publish privacy impact assessments, and make the rationale, legal basis, and purpose of broader access to the information clear and publicly available.

Questions 6, 17, 18, and 19

In your view, which of these options would it be most appropriate to take forward? Please give reasons for your answer, including your views about any risks associated with each option, and how it might help to achieve the government’s aims.

Which of the above options do you consider reasonable and proportionate to address the issues outlined in this consultation? Please give reasons for your answer.

If you chose options 3 or 4, which of the following data would you consider necessary and proportionate for the government to publish by default in order to identify a trust holding a particular piece of land, if further data is available under certain circumstances? Please tick all that apply and give reasons for your answer.

If you chose option 4, who do you think should qualify under a ‘legitimate interest test’ to allow access to further detail? Please tick all that apply and give reasons for your answer.

Since ROE was launched in August 2022, OO has analysed the data that has been made publicly and openly available via the Companies House website and its assorted data products. OO created a public data dashboard, refreshed monthly, to help better understand different approaches to beneficial ownership transparency reforms, assess whether it was achieving the stated policy aims, and help other users gain insights into data from the register. The dashboard was used by a number of UK journalists and international news organisations.

The dashboard offers a range of insights, including identifying the most common jurisdictions of incorporation of the overseas entities, the most prevalent nationalities of natural persons declared as beneficial owners, and identifying sanctioned individuals or entities appearing in the data.

Crucially, it also showed whether the beneficial owners being declared are natural persons, or entities such as companies or trusts. As of 8 February 2024, the data shows that while 28,997 individuals have been disclosed as beneficial owners of overseas entities, 12,178 corporate vehicles are listed as beneficial owners. This means that approximately 30% of the beneficial owners of overseas entities disclosed in the register are other corporate vehicles such as companies or trusts rather than the natural persons, and what international standards define as the beneficial owner. For many of these, it is not possible to find the natural person exercising ultimate ownership or control in other sources.

Further analysis conducted by researchers from the London School of Economics found that over 50% of overseas entities appearing in ROE hail from the three Crown Dependencies – Jersey, Guernsey and the Isle of Man – or the British Virgin Islands. None of these jurisdictions currently make beneficial ownership information available beyond government users, despite all having previously committed to do so by the end of 2023. This significantly undermines the government’s stated policy objective of ROE, of requiring the same transparency of the relevant overseas entities as of UK companies.

In light of the arguments above, OO believes that the “historical disparity between the information that is publicly available about most companies and trusts” constitutes a serious and unjustified barrier to the government’s transparency aims. Given that the government has established that there is a legitimate public interest in broader access to information on the beneficial ownership of companies, it should apply the same standards to all corporate vehicles. OO recommends the government undertake a comprehensive review of the collection, collation, and sharing of information about the beneficial ownership of trusts, beyond the ownership of land, including its integration with information on the beneficial ownership of legal entities, as explained in more detail further on.

In terms of determining which option is most appropriate to take forward, OO believes that this should be informed by the user needs of relevant parties beyond government, that can help the UK government achieve its stated policy aims. OO welcomes the government’s approach to “understand the minimum amount of information that is necessary and proportionate to meet objectives.”

Access provisions – including which data should be made available – and assessments of necessity and proportionality should be informed by user research and enable effective use of the information by these parties. End-users of the data outside government include members of the UK Anti-Corruption Coalition. Other users to consult should include individuals affected by the issues in the housing sector mentioned in the consultation, persons regulated under AML regulations, companies that develop solutions to assist these persons in meeting their regulatory obligations, and other companies that can use the information to conduct due diligence, including SMEs.

Almost all use cases of beneficial ownership information require it to be combined with other information to yield relevant insights. This means that the use of reliable identifiers for corporate vehicles, both in beneficial ownership datasets and others, is critical, as it allows datasets from different sources to be easily and accurately combined. Register-specific identifiers can be assigned to natural persons to help users with disambiguation for use cases that do not require combining the information with other datasets, and their use potentially justifies publishing less personal information than is currently available for beneficial owners of companies. However, this will not help with entity resolution and matching records for individuals when combining the datasets, for which users will still need to rely on secondary personal identifiers such as dates of birth, nationalities, etc.

Given that one of the stated aims is providing transparency, a minimum amount of information could be made publicly available. The user needs of key parties involved in tackling illicit finance and corruption to enable their effective use of the data is likely to be higher, including more data fields and a wider range of formats (e.g. in bulk or via an API). Examples include investigative journalists, CSOs, and academic institutions. Conversely, for some types of bulk analysis, the names of beneficial owners may not be necessary.

Another argument for ensuring at the very minimum some basic information to be made publicly available is deterrence. Research on ROE and a comparable measure implemented in the US, where information was only made available to authorities, showed that ROE had a more significant impact on real estate ownership through financial secrecy jurisdictions, suggesting that the fact that the information is made public has a deterrent effect.

If the government chooses to pursue the option of access with a legitimate interest test, this should not unduly restrict effective use. For example, investigative journalists and CSOs as a user group already have an evidenced track record of using beneficial ownership information and other datasets to help further stated policy goals, and should therefore be presumed to have legitimate interest by default, with access to data in a mode and format (e.g. in bulk or via an API) that enables a range of use cases, from in-depth investigation to quantitative risk analysis. Any individual affected by the housing issues mentioned in the consultations should also be considered to have a legitimate interest. This should be combined with approval on a case-by-case basis for unforeseen use cases, which the government should monitor and use to inform a regular review of the parties it considers to have a legitimate interest by default.

Questions 13, 15, and 16

Which of the following data do you consider necessary and proportionate for the government to collect (or continue to collect) in order to meet the objective of greater transparency of land ownership as a matter of public interest? Please tick all that apply and give reasons for your answer.

Which of the following data do you consider necessary and proportionate for the government to collect (or continue to collect) in order to meet the objective of helping to tackle illicit finance and corruption in respect of UK land ownership by overseas trusts? Please tick all that apply and give reasons for your answer, noting that overseas trusts are considered by the National Risk Assessment to pose a higher risk for money laundering.

Which of the following data do you consider necessary and proportionate for the government to collect (or continue to collect) in order to meet the objective of helping to tackle illicit finance and corruption in respect of UK land ownership by UK trusts? Please tick all that apply and give reasons for your answer, noting that UK trusts are considered by the National Risk Assessment to pose a relatively lower risk for money laundering.

Evidence shows that criminal actors use complicated networks of companies and trusts across multiple jurisdictions to hide and distance themselves from the proceeds of crimes and stolen assets. Tackling illicit finance and corruption therefore requires a transnational solution where a range of parties can access standardised beneficial ownership data from multiple jurisdictions that can be readily combined to better understand corporate structures and networks, and identify the natural persons behind corporate vehicles that own assets including land or real estate.

OO is advancing efforts to drive high-quality beneficial ownership data that is available digitally and can be more easily combined, analysed and used. The organisation is at the forefront of technical and policy developments to create standardised, structured, and interoperable data, and has developed the Beneficial Ownership Data Standard (BODS), the leading global standard for beneficial ownership information. BODS provides a technology solution for sharing beneficial ownership data so that it is interoperable with other datasets. The standard has been adopted by multiple national governments including Armenia, Canada, Latvia, and Nigeria, with more countries planning adoption in 2024, or committed to do so in the future.

In March 2022, following a yearlong government consultation led by the UK Data Standards Authority, BODS was approved as the UK government’s official open standard for the collection, exchange, use, and distribution of beneficial ownership data. The Data Standards Authority team later stated that adopting BODS would help the UK government achieve the goals of its economic crime reform package. OO encourages the UK government to take the next step by implementing the use of BODS to facilitate the interconnectedness of its data between corporate vehicles, including companies and trusts, and with other jurisdictions.

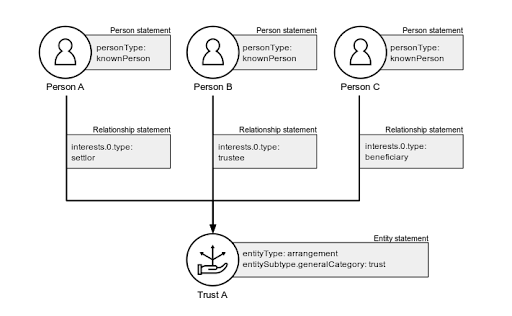

As mentioned, within corporate structures trusts can own assets, including legal entities, and legal entities can be party to a trust. This makes it important to have a standardised way to collect and connect data on legal entities such as companies with legal arrangements such as trusts. BODS is arranged around a data model where statements about people, corporate vehicles – including legal entities and arrangements – and the relationships which exist between them can be linked together to represent simple or complicated ownership networks which can involve different types of corporate vehicles from one or more jurisdictions.

By structuring data in line with BODS, information on the beneficial ownership of arrangements such as trusts can be readily combined with information on other corporate vehicles – for example, where a trustee is a company. Collecting data fields such as identifiers, addresses and dates of birth helps with efforts to uniquely identify people, entities and arrangements in such networks.

The latest version of BODS already allows for the collection of all of the following fields set out in questions 13, 15, and 16:

- Name of trust (or other identifier)

- Name of trustees

- Name of beneficiaries

- Name of settlors

- Name of protectors (if applicable)

- Details of land owned by the trust

- Beneficiaries’ rights over the land

- Address(es) of parties to trust

- Dates of birth of parties to trust

In version 0.4 of BODS – due for release in the first half of 2024 – OO will publish comprehensive guidance documenting how to represent trusts and trust-like arrangements in BODS. This draft guidance can be viewed here ahead of the launch of version 0.4 and includes explanations of a number of scenarios where trusts or trust-like arrangements are involved in beneficial ownership networks. To uniquely identify specific individuals, build detailed beneficial ownership networks, and understand the assets connected to a particular trust, it is important to capture all of the data fields laid out in the consultation questions.

OO has also explored questions relating to the disclosure and registration of trusts as well as the beneficial ownership transparency of trusts. These and other resources can be found on the trusts and legal arrangements page of the OO website. Collecting standardised data on the beneficial ownership of trusts will support the aims set out by the government in this consultation, in terms of linking information from different registers.

Every month since 2017, OO has converted the latest beneficial ownership data from the UK’s People with Significant Control (PSC) Register in line with BODS and republished this as open data, enabled by the data from Companies House being licensed by statute. OO currently ingests, maps, and transforms this data in line with version 0.2 of BODS before making it searchable via https://register.openownership.org or available for anyone to reuse in a range of formats at https://bods-data.openownership.org/source/UK_PSC.

As the UK government’s own guidance states, using BODS “will make your technical systems more interoperable with others, and improve collaborative work with data across government. It can also reduce the need for people who need to give data to government to give it more than once.”