Understanding beneficial ownership data use

Research findings: Towards a framework to better understand the use of beneficial ownership information

Users of BO information have a wide range of purposes, ranging from identifying and managing risk as a business, to detecting conflicts of interest in public procurement. Each user tries to answer questions for a specific purpose, including, for example:

- identifying a specific individual suspected of illegally owning and enjoying the benefits of assets;

- identifying domestic tax residents who may be misusing legal vehicles to evade taxes;

- identifying links between politically exposed persons (PEPs) and companies that operate in strategic and sensitive sectors;

- providing due diligence of potential suppliers, corporate clients, or contract bidders;

- monitoring trends in ownership concentration to help understand and regulate competition;

- identifying indicators of red flags for money laundering and corruption risks.

The range of questions users seek to answer is indicative of the diversity in BO data use. Even when sharing a purpose, users seek to answer different questions. These questions and the information users start with determine how BO information is used.

The following two sections explore the commonalities and differences among users’ experiences and needs in answering their questions. The last section distils implications for policy makers and agencies in charge of designing and administering BO registers.

Common user experiences and needs

The research identified a large number of commonalities among user needs associated with various use types. These common experiences validate many elements of the Open Ownership Principles. [7] These include:

- having effective access to usable information;

- retrieving relevant and usable information;

- understanding relationships between subjects within and across information sources;

- having a minimum level of accuracy to draw conclusions with confidence.

Having effective access to usable information

The use of BO information starts with the need to access it. However, a large proportion of users still face major challenges to accessing the data they require. Despite a significant increase in the number of jurisdictions implementing BOT reforms, there is still significant divergence between jurisdictions in terms of the availability and quality of information as well as modalities of access. The latter can sometimes mean information is not up to date, if accessible at all. These points were largely echoed by the research participants. For example, this participant working for a tax authority explained how direct access to information is beneficial for addressing tax evasion:

“The quicker you can get evidence, the better. Having direct access to BO information saves a lot of time. When you don’t have direct access, as tax administrator, you would need to write to an individual or company or to the registrar and, legally, they have a week to provide the information. If they don’t, we can send a first reminder. Then, a second. If they only provide partial information, they can also ask for more time to provide it completely. Only then comes enforcement. This process can easily take over three weeks.” [8]

These issues are particularly pronounced when users try to access information from a different jurisdiction. The lack of availability of BO information for non-domestic legal vehicles remains a significant barrier for a majority of use types. An investigative journalist participant explained: “I mostly work on cases involving tax fraud and links to tax havens. All cases I worked on involved transnational links. You will always need to go to another country’s register”. [9] Yet, non-government users are often unable to access this information, and many heavily rely on open sources, such as the investigative data platform Aleph by the Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project (OCCRP), which gathers multiple types of information in one place. [10]

A number of research participants also mentioned challenges to accessing BO information on specific types of legal vehicles, such as trusts and other legal arrangements, both domestically and in other jurisdictions. Such legal vehicles are not always subject to registration requirements and can constitute blind spots in the networks of relationships between individuals, legal vehicles, and assets, or BO networks. [11] Where registration is required, there may be different access provisions which prevent effective use of the information. One research participant, who uses BO information to understand the ownership and control of land, explained: “This is where the trail goes dead”. [12]

Finally, as will be illustrated throughout this report, in many cases, users can only access information and process data in ways that do not allow them to answer their questions. The research findings suggest that access regimes with tiered access based on a categorisation of users relating to their profession or sector risks glossing over similarities and differences between various use types.

While this categorisation can be useful to initially map user profiles expected to use BO information – as was also done for this research – and ensure the right individuals have access to BO information, the findings suggest that in most cases these access provisions do not respond to user needs.

Retrieving relevant and usable information

Irrespective of the purpose they are working towards, users may start their initial inquiry either with some specific real-world information (e.g. information about a customer, lists of sanctioned individuals, information about companies bidding for a public tender) – or with an initial set of criteria (e.g. nationality of beneficial owners or jurisdiction of incorporation).

The research found that a broad variety of criteria is used by research participants to query BO data. This suggested that potentially all attributes (i.e. data fields) pertaining to a subject (i.e. individual, legal vehicle, or asset) may be relevant to help users complete various inquiries along their journey. Examples of attributes deemed useful, as reported by research participants, included: day, month, and year of birth; email and residential address of individuals; country of residence of individuals; registered address of companies; nature and level of ownership interest; tax and identification numbers; IP address of declarant; individuals’ nationality/ies; and PEP status of beneficial owners. Which specific attribute was deemed most useful in which case was highly context- and query-specific, and no particular attribute could be associated with specific use types or user profiles. Being able to search a register by the names of beneficial owners was seen as extremely useful in almost all cases.

A number of participants mentioned that limited search functionalities hindered their capacity to query BO registers using criteria that were relevant to their lines of inquiry. Some mentioned that they used bulk data or APIs as an alternative way to search BO registers more effectively or to enhance searches by connecting BO information directly to other datasets. [13] This suggests that improving register functionality and searchability can lead to better data minimisation. A data-service provider explained: “With an API, when you are doing an investigation, you can look up that one person or company and pull extra information about it”. [14]

A large proportion of research participants also mentioned needing historical data. Information about change over time is crucial to help detect risks, as illustrated by the quotes from research participants below. For example, frequent changes, suspiciously timed changes, or changes from a declared beneficial owner to a family member may be useful red flags. Historical information is also necessary to monitor trends over time. Two research participants explained:

“If you get a lead, it’s often based on what happened in the past. You often look at who used to own a company. You can look at changes to spot potential red flags. You can’t have the full picture unless you see the history.” [15]

“Historical changes are very important. For example, if you notice that a trust is created all of the sudden, after a person was sanctioned, it can raise a red flag.” [16]

This underscores the importance of ensuring that the BO information disclosed is up to date and periodically confirmed to be accurate, with the information clearly showing what changes were made, when, and why, to make it auditable to data users. [17] Up-to-date information was particularly appreciated as some other valuable sources of information such as data leaks only provide a snapshot in time. [18] Research participants also valued being notified of any changes in the information of a company of interest. This functionality is provided by some BO registers. Some commercial providers connect BO data to other sources of information, widening the range of red flags users can be alerted to (see, for example, Box 2). [19]

On a more basic level, users may not necessarily know where to find the information they are looking for from BO registers in multiple jurisdictions. [20] Where BO records are only accessible upon request, users may not know whether a register holds relevant information until the request is satisfied. Where BO information is directly accessible to users, both not knowing the language or which authority is responsible for the register were flagged as barriers by some users. As one research participant explained: “Sometimes I want to check the BO register of a specific jurisdiction, but as it is not in my own language, I may not always be sure of whether I’m looking at the official register or some private platforms that only summarise information held on official registers”. [21]

Tools that help with signposting can be useful to address these barriers. Open Ownership recently tested this by developing a prototype single-search platform that used APIs of BO registers to signpost users to where they might find information on particular companies or individuals. After testing the prototype with a selected group of users, it found that such a tool could support users by helping them find information they did not know existed, and by saving time in retrieving information. However, it did not meet many other needs identified through this research. [22]

Understanding relationships between subjects within and across information sources

In the large majority of cases, BO information is not used in isolation. It is one of many information sources that help users to answer their questions and be confident in their conclusions. The process of establishing relationships between subjects in different sources of BO information and other types of datasets (e.g. company and asset registers, as well as PEP and sanctions lists), often across multiple jurisdictions, is at the core of the majority of use types (see Box 5). Most user needs serve this practice, as illustrated by a research participant working for a commercial provider that seeks to enable its users to do this:

“We have developed mapping tools for clients like investigative journalists, data-service providers, law enforcement, and financial institutions and it’s all about helping them combine one or more datasets to get insights. This is ubiquitous across the world ... Beneficial ownership data is key to connecting the dots between a client and company or legal person and other entities.” [23]

This process requires entity resolution and ways to uniquely identify individuals and legal vehicles. Entity resolution is the process of establishing whether multiple records about a subject (e.g. individuals, legal vehicles, or assets) are referring to the same subject or to different subjects. Identity verification refers to the process of determining to which real-world individuals or legal vehicles these records correspond. Although these processes are different, entity resolution can be achieved through identity verification.

Entity resolution is practically always necessary when using multiple information sources (see Figure 2), and sometimes necessary within a single information source (see Figure 1), depending on the information provided. It usually involves comparing a number of data points or attributes of a subject in a record to see whether they match. As subjects may have identical or very similar attributes (e.g. names), additional attributes can provide confidence as to whether two records are referring to the same or different subjects. Some attributes (e.g. identifiers) provide more confidence for entity resolution than others. Generally, the greater the number of matching attributes, the higher the confidence in entity resolution. Registers provide varying amounts of information that can be used for this purpose, meaning it takes different levels of resources to conduct entity resolution (see Box 1). For example, some BO registers, such as Denmark’s CVR, uniquely identify individuals using a register-specific identifier.

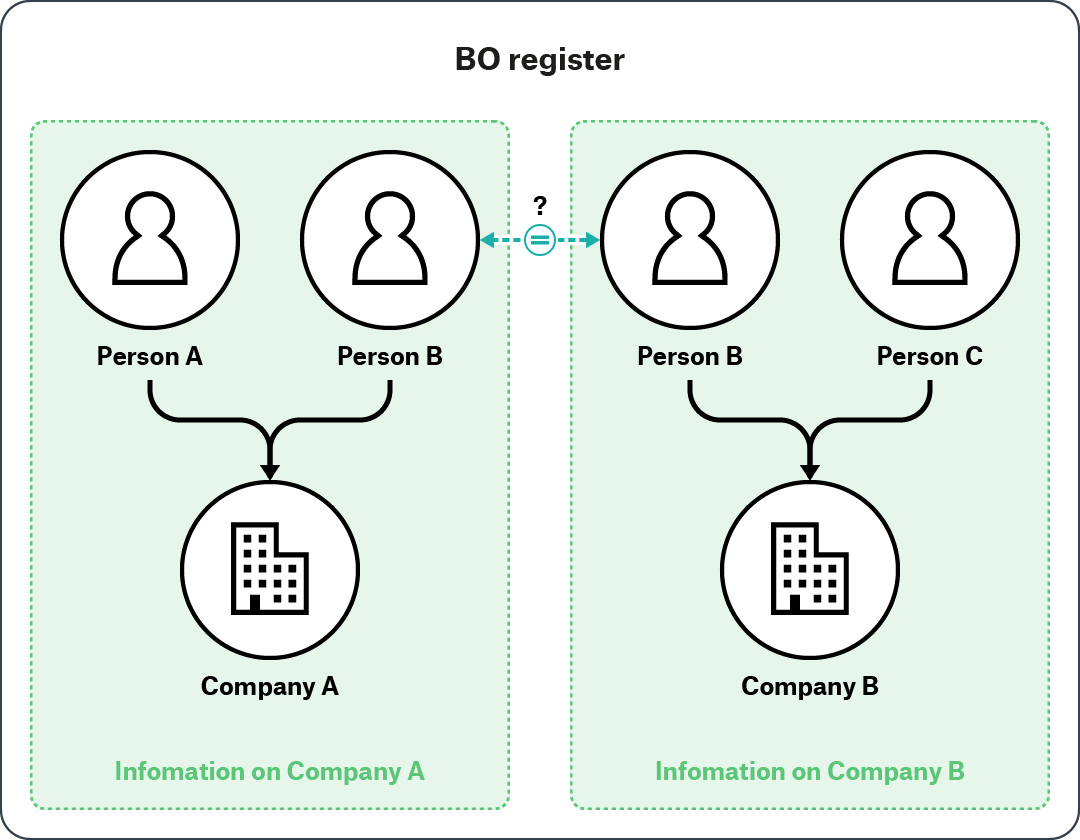

Figure 1. Entity resolution within a single information source

In this example, a user may look up Company A in a BO register. The user sees that Company A is related to Persons A and B. The user subsequently sees that Person B also appears to have a relationship with Company B, which in turn is related to Person C. To conduct thorough due diligence on Company A, the user may need to resolve whether the Person B in the information declared by Company A refers to the same Person B in the information declared by Company B.

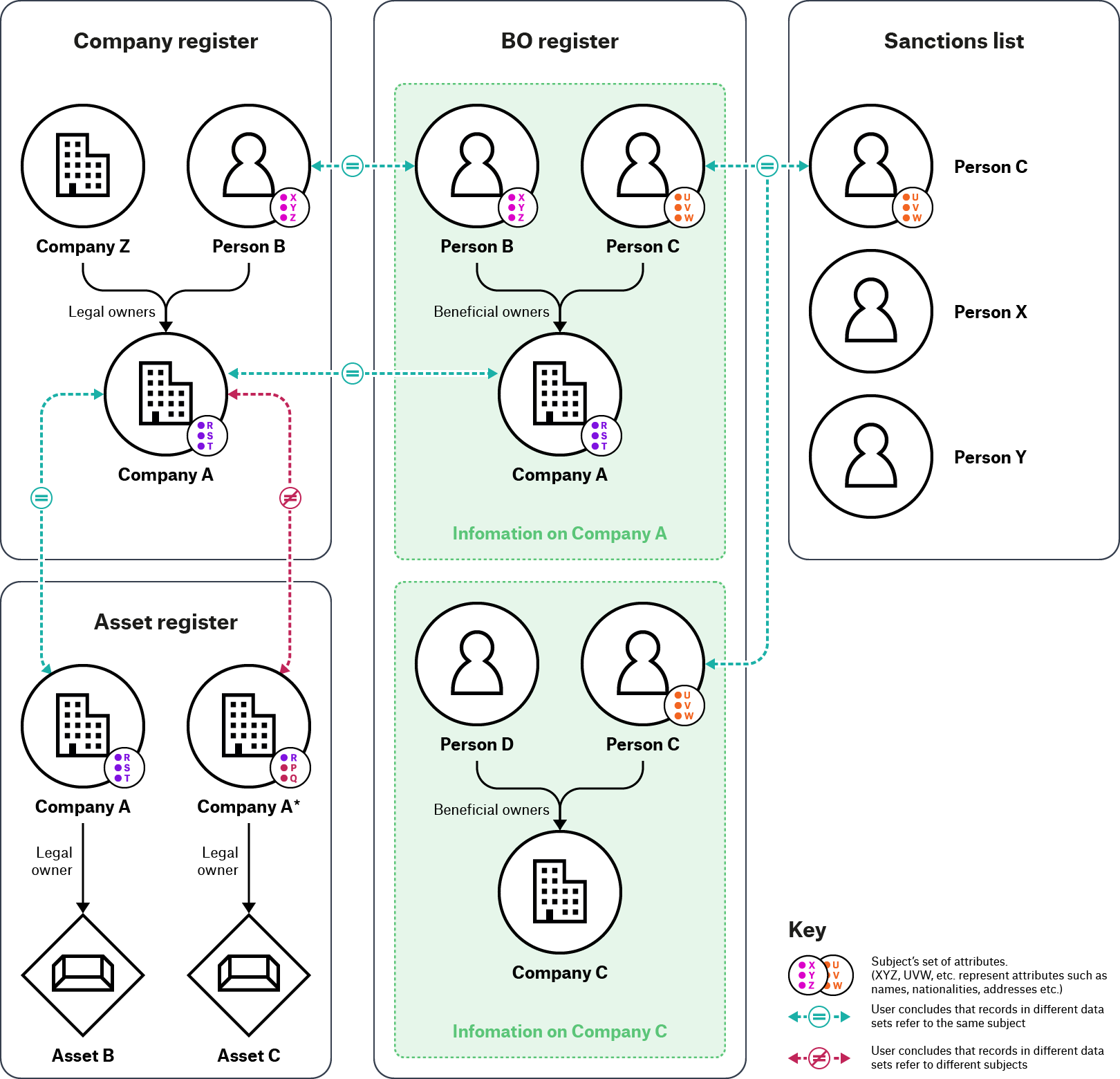

Figure 2. Identifying relationships and resolving entities across information sources

In this example, to perform due diligence checks on Company A and subjects related to it, the user needs to cross-check information in the Company register, BO register, Asset register and Sanctions list. The user checks information about Company A in the Company and BO registers and sees that Person B is listed as legal owner of Company A on the Company register and as beneficial owner of Company A on the BO register. To establish whether records about Person B in each register refers to the same or different individuals, the user checks if the attributes recorded about them in different registers have the same value. The user concludes that records about Person B in these two registers are referring to the same individual when enough or particular attributes about their records match. The user repeats the same process to cross-check records about Person C in the BO declarations of Companies A and C on the BO register, and on the Sanctions list. The user also checks the Asset Register and finds two records about Company A with slightly different spelling for Company A (A and A*). To double-check whether these records may refer to the same or different Company A listed on the Company and BO register, the user repeats the same process and concludes that Company A on the Company register and Company A on the Asset register refer to the same company. However, as two of the attributes of Company A* on the Asset register don’t match with the attributes of Company A, the user concludes that Company A* refers to a different company.

Box 1. Entity resolution in the United Kingdom’s beneficial ownership register [24]

Monitoring and addressing risks linked to ownership concentration is a concern for competition regulators, such as the United Kingdom’s (UK) Competition and Markets Authority (CMA). The CMA uses BO information from the UK’s BO register to analyse the concentration of ownership in specific sectors once common ownership and control are taken into account.

However, the UK does not provide sufficient information to easily see whether records about individuals relate to the same or different individuals. The CMA reports: “The data available from [the UK BO register] does not contain unique identifiers for individuals or corporate entities that are recorded as [beneficial owners]. As a result, it is not straightforward to understand from the data whether one individual or entity holds control in multiple companies”. [25]

As a result, the CMA has to rely on personal attributes (e.g. names, dates of birth, and nationalities) for entity resolution, which is resource consuming and less reliable.

Reliable identifiers

The use of reliable identifiers in different data sources enables entity resolution and identity verification. A reliable identifier is a number or reference code which is unique and stays the same over time. [26] Examples of reliable identifiers issued by authoritative government bodies to individuals include passport and national ID numbers, social security numbers, and tax identification numbers (TINs). For companies, examples include company registration or incorporation numbers, TINs, or LEIs. [27] Some participants’ insights point to the importance of trust in the agency that provides identifiers. For example, the financial industry includes a number of ISO standards which recommend specific identifiers. Industry actors have, for example, advocated for LEIs as a data requirement for standard ISO 20022 related to cross-border payments. [28] “Making LEI disclosure mandatory when it’s available under ISO 20022 will be a big help in the sanctions world, as it is considered a trusted source”, explained an expert from the sector. [29] However, these are currently still missing in many information sources (e.g. land registers and procurement data). A research participant studying indicators of corruption risks explains:

“Most procurement datasets don’t have reliable company identifiers, or there is incomplete coverage so it’s hard to match with BO datasets. This might be one of the main reasons BO data is not being used in procurement currently.” [30]

Entity resolution for natural persons

Entity resolution for natural persons is particularly challenging due to the privacy-sensitive nature of reliable identifiers for individuals (e.g. national IDs and social security numbers). Many registers do not distinguish whether records about a subject refer to the same or different subjects, or provide sufficient information for users to easily do so with confidence, for instance, by providing register-specific identifiers (see Box 5). Commercial providers are trying to address this by using technological solutions to digitally verify the identities of companies and individuals. [31] The EU has been working on harmonised solutions, such as the European Digital Identity wallet. [32] However, users need alternatives while these solutions are still being developed.

When the same identifier is not used across multiple datasets, users require additional attributes to reach sufficient confidence to disambiguate records about natural persons (e.g. personal information such as full name, date of birth, nationality/ies, phone number, etc.). The more attributes that can be compared, the more confident the user can be in their conclusions. Often, these additional attributes are needed when there is a lack of reliable identifiers for individuals. One participant noted: “There are many John Smiths in the world. The more you can hone down (for example, through day of birth rather than only month and year of birth), the more helpful. Data processing and time to investigate is greatly reduced if you have this”. [33] Register-side entity resolution and publishing identifiers for individuals will lower barriers to data use. As a result, it may not be necessary to access and process as many different attributes for individuals. Because these identifiers are likely to be domestic or register-specific, additional attributes may still be necessary when using multiple information sources.

Structured, standardised, and interoperable information

A number of research participants also reported facing challenges processing and analysing information from multiple sources due to the fact that these used different data formats. There is a need for better structured and more standardised data, as illustrated by this participant working in public procurement:

“Having much clearer standards on how names, dates of birth, etc. are structured, and on using identifiers, would make the process of name matching and linking a lot easier and more straightforward.” [34]

When information sources are structured well as data and include reliable identifiers, the information is more interoperable. This makes it easier to use and enables the information to be more readily ingested into other systems, as illustrated by the use of commercial data services (see Box 2). The lack of standardisation in how information is structured can pose challenges to users trying to understand transnational BO networks, as explained by this European journalist who leads investigations on tax fraud:

“At the moment, one of the biggest barriers is the lack of harmonisation, transparency, and availability of BO information across different countries in Europe. The biggest need is greater cooperation between countries. Regional institutions such as the EU could support the development of centralised registers with common standards.” [35]

The extent to which information from different sources is usable also depends on users’ knowledge and resources. For example, a research participant working for a non-governmental organisation (NGO) explained the importance of data-analysis skills to use information from various datasets. He explained: “A lot of the information is still stored by PDFs and data scientists have to spend a lot of time doing things manually. This is especially resource intensive when going through big datasets that have millions of records. Entity matching between property datasets and company owners is a good example of that”. [36] Many users rely on commercial datasets run by private providers to cross-check information (Box 2).

Intermediary data users

To address these challenges, many users rely on intermediaries, who play a key role in addressing barriers to data use (see Box 2). However, there are also practical barriers to accessing commercial datasets. For example, major banks that regularly conduct due diligence on hundreds of thousands of clients may have the capacity and financial resources to use and embed commercial solutions into their own systems. On the other hand, departments in smaller banks may not even have access to a company credit card to procure these services. [37] This may also apply to some government users. Research participants from civil society explained how non-profit organisations may not always be able to afford these services, although some do. [38] Government users also mentioned appreciating publicly accessible BO registers, which allow them free and direct access to information from other jurisdictions. Public access to structured information is therefore associated with efficiency gains, even for users whose right to access is secure. One research participant working in public procurement explained:

“Everything international is commercial. ... In terms of time and money saved going to each register and building integrations, it probably makes more sense to pay for a commercial service. … But open source would create longer term savings for governments.” [39]

Box 2. The role of data intermediaries in filling current gaps to access and process beneficial ownership information

Data intermediaries provide data (e.g. combined, cleaned, and structured) and services (e.g. data-use platforms and tailored tools) to help end users achieve their aims. They help overcome challenges in access to and usability of BO registers.40 Data intermediaries are a crucial part of the data-use ecosystem. Their work often includes combining BO information from different jurisdictions and with other types of information. This often involves entity resolution and adding attributes to subjects (e.g. insolvency information for companies, adverse media information for individuals). Examples include commercial providers that clean and aggregate data from various data sources, including BO registers and providers of services like entity resolution, as well as non-profit organisations that create public tools which link and match BO information to other datasets.

The services provided by intermediaries also include providing historical BO information where these may not appear in a register or making information searchable by additional criteria. They are also used to overcome the cost of using information in different formats. Even when these are free, there is a cost to mapping a new format to make it readily usable in local systems. Commercial providers use and rely on information from government sources. They are, in turn, also used extensively by governments themselves. Some use commercial providers to retain anonymity in accessing information.

To provide the services that support end users with their use of BO information, data intermediaries have emphasised the importance of APIs and bulk data to integrate BO datasets into the services offered to end users. [41] One research participant explained: “My entire world is bulk data. Bulk data allows you to cross-reference data sources”. [42] Where information is accessed on the basis of legitimate interest, effective access procedures are required. [43] Research participants also echoed how using unique identifiers across different datasets helps to collate data. When it comes to entity resolution, intermediaries mentioned that anything that can help them link records about subjects in different information sources facilitates their work. They also emphasised that the more attributes there are, the better entity resolution works. [44] One research participant, a data-service provider, explained:

“Our algorithm is entity-centric and it works like an investigator with a folio. The more data sources it can use, the more it can learn the attributes just like a person would. The entity-centric algorithm will make use of any attributes you give it. The more data you provide, the better it performs. If you’ve assigned something specific to your data, like company IDs, and you add a data source that already includes those IDs, that’s great. But unfortunately, this is rarely the case.” [45]

Application programming interfaces and bulk data

Using and combining multiple information sources – and resolving entities across these sources – can be difficult without appropriate access to APIs or bulk data. For example, in their analysis of real-estate ownership in France (see Box 3), Transparency International France and the Anti-Corruption Data Collective had to go through five million web pages, taking several weeks and using significant resources to connect BO and real-estate information. In their report, they explain that not being able to access data in bulk created “a significant barrier ... in monitoring the implementation of the beneficial ownership rules”, and that “access to beneficial ownership information in an open data format – or even better, API access – allows key actors to more effectively use the data”. [46] This suggests that registers which only provide access through search portals, only allowing limited flexibility in ways to search and process information, are likely to be less impactful than where information is structured and available in bulk or via APIs. [47]

Understanding full beneficial ownership networks

Tools that help understand full BO networks are extremely valuable to users, as one participant describes: “It is not only about the visualisation, it is also about having all the information together”. [48] A participant from a law enforcement agency explained: “Before the BO register, we would just use the company register to look at information on directors [and] shares, and try to work our way through complex corporate structures step by step. This was time consuming”. [49] Other research participants have mentioned being particularly interested in the network and structures, rather than the individuals at the end of the chain. They mentioned using BO information as a means to this end where shareholder information was of poor quality or not available. A limited number of BO registers collect and share information on intermediaries and direct interests. Shareholder information is highly valued, but it is often not available or up to date. [50]

In addition, a number of use types involve trying to understand relationships between a large number of legal vehicles, individuals, and assets over time. As these networks can be difficult to comprehend, many users want tools that visualise these relationships. Structuring data in ways that can easily be turned into graph formats was therefore noted as a common user need.

Having a minimum level of accuracy to draw conclusions with confidence

In many cases, using BO information includes verifying it by cross-checking information from different data sources, in a similar way that BO registrars verify information for accuracy. Information is used in verification much like it is with entity resolution: attributes about subjects in different sources of information are checked against each other. Rather than establishing whether they refer to the same subject, the aim is to verify whether any of the information is inaccurate. This process increases confidence in the conclusions drawn from the information, but also costs resources. Users verify BO information for a range of purposes, including:

- A statutory obligation to verify information using other information sources. This is often the case for users working for AML-regulated institutions and some government agencies. [51] A research participant from the financial sector explained what this process consists of for them. For new clients, they must ensure that the identities of an entity and the individuals associated with it are verified based on information and documents supporting the application. This includes the identity of the beneficial owners and the ways through which they exercise their ownership or control over the legal vehicle. They use multiple information sources to cross-check the information that is provided. The participant explained that BO information is sourced in three stages: first, it is collected by the bank; second, it is checked against information in the domestic BO register and registers in other jurisdictions; and third, BO information about any other subjects discovered in the network who were not identified in earlier stages is checked against information from other registers. [52]

- Research participants from law enforcement agencies explained that, in financial crime investigations, some information can serve as intelligence, but it does not satisfy the standard to be presented as evidence in court. They cross-check information from information sources including from BO registers, informal intelligence-sharing channels, banking information, and formal requests for information through mutual legal assistance to foreign authorities. [53]

- Mitigating reputational and legal risks. For example, research participants from the media mentioned how crucial it is to be highly confident that data-driven conclusions are corroborated by multiple sources, especially where it may involve allegations against powerful actors. One research participant explained: “Inaccurate data can cost you a lot as a journalist: it can lead you to prison”. [54]

- NGOs doing research on extractive companies verify information against local knowledge to detect false declarations and hold extractive companies to account, for example, on whether a company operating in their area may be using a front person as its owner. [55]

The research found that although users verify the information, they do not necessarily require it to be perfectly accurate. Research participants from both the media and law enforcement pointed out the value of gaps, inaccuracies, and discrepancies in and between information found across several sources. An inaccuracy in one field was not necessarily seen to undermine the value of the BO declaration as a whole, and can serve as a red flag for further investigation and cross-checking with other information sources. One research participant, a Danish journalist, explained:

“Data ... may not always be 100% correct but, when it is not, it still allows you to ask critical questions. … It is a very important tool to fact check something or start an investigation.” [56]

Furthermore, the obligation to disclose creates a legal liability for providing false information. A participant from law enforcement pointed out that the sanctions around providing inaccurate BO information also provide greater opportunities for law enforcement bodies to pursue action against the subjects of their investigations. [57]

While inaccurate or missing data can help raise red flags or further investigations, it is harder to do so if accidental errors are ubiquitous. One research participant explained: “If the wrong fields are used – for example, a company name is disclosed where it should be the owner – suddenly it becomes very difficult to understand the data and know if there is an actual owner”. [58] Another participant shared that: “Sometimes you come across missing data points, incomplete records on PEPs, or inconsistencies in how beneficial ownership information is updated across platforms. Involving CSOs [civil society organisations] helps ensure there is as an additional layer of verification, flagging discrepancies that might otherwise go unnoticed”. [59] Regardless of their rationale for verifying data, ultimately all BO data users require a baseline level of accuracy to feel some level of confidence in their conclusions. This includes ensuring that information is regularly updated.

Different use types and user needs

Although there are overwhelming similarities in user needs, some differences were identified in the research. To test the first assumption, the research team interrogated whether there were various ways of using BO information (use types) and explored whether user needs differed depending on the use type. This led to developing the following framework, which identifies different user needs based on the following core elements:

- whether the question the user is asking is qualitative or quantitative in nature;

- the scale of data processing required to answer the question, i.e. the number of subjects (e.g. individuals or legal vehicles) users are interested in;

- the scope of data processing required to answer the question, i.e. the number and variety of connections or relationships between different pieces of information required for users to reach their conclusion;

- the frequency of data processing required to answer the question.

Nature

A user’s question can be quantitative or qualitative in nature.

- Quantitative questions: These queries look for numbers or patterns. The interest of users who address these questions is in quantifying something rather than identifying specific people or legal vehicles.

- Qualitative questions: These queries look at specific attributes of specific legal vehicles, individuals, or both. Therefore users will likely need to identify these specific vehicles and individuals.

Box 3. Examples of use types with a question of quantitative nature

In 2023, Transparency International France and the Anti-Corruption Data Collective combined publicly available BO information in France with information from the real estate register to look into ownership of France’s real estate sector. They found that nearly 71% of all company-owned titles were held by anonymously owned companies. [60] Prior to this, the NGO Reporters Without Borders and the French academic institution, the Laboratory for Interdisciplinary Evaluation of Public Policies, explored ownership concentration in the French and Spanish media sectors and published a report stating that over half of each sector was controlled by companies from the financial and insurance sectors, whose complex shareholding structures made it hard to identify the beneficial owners.

Users whose questions are of a quantitative nature are likely to be able to answer their question with pseudonymised data by using unique identifiers in place of companies’ and individuals’ names. For example, a user seeking to assess the proportion of legal entities whose declared beneficial owner is a legal minor will need to be able to access beneficial owners’ dates of birth. Yet in this example, they would only need to process dates of birth without needing to identify individuals.

If policy makers and agencies in charge of administering BO registers make, at a minimum, a pseudonymised dataset available, this may enable certain types of data use. However, users with qualitative queries will likely not be able to fulfil their task without needing to process personally identifiable information. This could happen when, for example, a user wants to conduct due diligence on a legal entity as a potential supplier, or when a user is trying to investigate a specific individual or legal vehicle suspected of criminal or fraudulent activities.

Scale

A user’s question will determine the scale of information required to be processed in order to answer it – that is, the potential number of subjects of interest in the information processed to answer the question. The information users start with often influences this.

- Large-scale: Users may (i) start with a large amount of information (e.g. lists of entities or individuals), or (ii) need to identify relationships or patterns across an entire BO register. Most users with quantitative questions looking for patterns mainly require large-scale processing. However, qualitative questions may also require large-scale processing. Generally, large-scale processing means that processing the data manually would become a critical barrier to the user being able to answer their question. To conduct large-scale analyses requires ways to easily process large quantities of data. This makes the use of APIs and bulk-data access particularly important to enable these use types (see Box 4).

- Small-scale: Users operating on this scale are often, but not exclusively, addressing qualitative questions. They will most likely be interested in a small number of specific entities or individuals and their attributes, and are often able to process data record by record without it causing an undue burden or affecting their ability to answer their question.

Box 4. Examples and insights from users with experience of large-scale data processing

Researchers from the Central European University studied whether BO data could be used for largescale risk assessment in public procurement as a quantitative query. This involved analysing procurement and BO datasets for six jurisdictions. Their analysis validated jurisdiction-specific indicators of corruption and money laundering in BO data in relation to public procurement. [61] In addition to highlighting the need for structured data with historical records of changes, the researchers have also emphasised the importance of bulk data and, ideally, APIs to enable this type of analysis. [62]

Users across law enforcement, tax authorities, and civil society conduct large-scale qualitative analyses aimed at identifying and monitoring risks. Two representatives from a law enforcement agency and a tax authority from Europe and Africa explained:

“We ingest bulk data from Companies House into our own data holdings. That helps more proactive analysis and creates opportunities for investigation. In terms of data exploitation capability, you can query information about a large set of corporations and identify linkages that are not immediately apparent.” [63]

“Dealing with specific people who would do anything to avoid paying taxes and need to be investigated is different from looking for trends and identifying certain sectors and profiles that are high risk. ... For trends and profiling of taxpayers, we need to be able to detect patterns of things that are suspicious. For example, if a self-declaration always says ‘null’ or includes changes in legal and beneficial ownership.” [64]

Being able to query a whole dataset flexibly using an API supports this. For example, one research participant explained that it can be useful to be able to find information on every company with a director from a specific nationality. [65] A participant from a tax authority echoed this, explaining that the search engines they use internally within their agency enable them to set up rules to support risk assessment and identify taxpayers who fit a certain profile. They explained: “For example, you can ask to see anything that involves change in shareholding or that includes a null declaration of revenue. Having something similar with BO information would allow adding more triggers and make your risk identification process richer”. [66]

Another research participant working for an FIU mentioned API availability as a key factor facilitating their work, including through the domestic BO register. They mentioned a long list of other government agencies and information sources the FIU was connected to, including customs, national identity, road safety and traffic, immigration, the tax authority, the central bank, the security and exchange commission, as well as a number of regulatory organisations, such as the agency supervising the real-estate sector. [67] The founder of a software company that provides services to support anti-financial crime actors further explained: “There is a lot of value in integrating bulk data. When you enrich your own data with third-party data, then you can compute risk scores and detect alerts across the entire dataset”. [68]

Scope

The scope of data processing refers to the number and variety of connections a user needs to identify in a line of inquiry. This can range from using BO information from a single BO register, to trying to identify connections between subjects across multiple data sources. The type of information users start their data-use journey with also influences this.

- Queries may be limited in scope and only require BO information from one BO register to answer their question. This may include looking at relationships between a limited number of different individuals, or between different companies. A limited scope can make data processing relatively simple. However, the research found that this only represents a small number of use types.

- In extensive queries, users need to identify relationships between multiple subjects. This can happen either within a single BO register or across BO registers, and can involve additional datasets (e.g. public contracts, PEPs lists, etc.), and other information sources (e.g. companies’ websites, media sources, etc.). The research found that this represents the majority of cases.

On this spectrum, users who require extensive data processing have a greater need for mechanisms to facilitate the process of identifying connections between subjects (Box 5). This makes investment in mechanisms to support entity resolution and identity verification particularly important to enable these use types.

Box 5. Examples and insights from use types with different scopes of data processing

A tenant may want to identify the beneficial owners of a company that owns their apartment. In the United States of America, limited liability companies with anonymous owners are associated with housing disinvestment, poor housing conditions, and causing delays in tenants accessing funds through government schemes. [69] This is a relatively straightforward query that is limited in scope. The user may only identify one or a handful of relationships between their building owner and the individuals behind it.

A user interested in the level of compliance with legal BO disclosure obligations may ask How many companies have not disclosed any beneficial owners? [70] This is a quantitative query that requires large-scale processing, but is still limited in scope.

By contrast, in a major case of alleged corruption and stolen assets, Nigerian law enforcement agencies and the FIU used a variety of information sources, including the company register, the Crime Records Information Management System, open-source intelligence, reports from financial institutions, information from their own database, and exchange of information channels with FIUs in several other jurisdictions, to map a network of individuals and legal vehicles and trace USD 1.7 billion of missing funds. [71] This required a very extensive scope of identifying relationships between subjects and across information sources.

Frequency

Users can require processing information either on a single or a recurring or ongoing basis:

- In the case of one-off processing, users only need to answer their questions at a specific point in time.

- Recurrent or ongoing processing means a user needs to process information multiple times or on an ongoing basis in order to answer their question. For example, generating an up-to-date, real-time picture of risk will require processing – and in some cases ingesting – BO data on an ongoing basis (see Box 6). Depending on the scale of the query, this may not be feasible without register features, such as automated alerts, streaming APIs, or access to up-to-date information in bulk.

Box 6. Examples of use types working on an ongoing basis

Data journalists and researchers from Colombia, Mongolia, and Nigeria combined various public information sources and developed analysis tools for accountability and oversight of the extractive sector. For example, the Mongolia Data Club combined data on legal and beneficial ownership, procurement, and other sources into a digital platform aimed at better understanding the activities and connections of suppliers of state-owned enterprises in the mining sector. [72] Journalists and researchers used their training and tools to explore various questions, such as interrogating the allocation of coal transportation permits from Mongolia to China. [73] Journalists also explored corporate ownership of candidates in national elections to provide public oversight and shed light on any potential conflicts of interests. [74]

In Nigeria, Directorio Legislativo partnered with BudgIT to build the Joining the Dots platform, which combines BO information, PEPs lists, and mining licensing information to monitor links between politicians and mining licences and automatically raise red flags on a continuous basis. [75]

To facilitate sustainable public oversight, the tools developed by Mongolia Data Club and Directorio Legislativo require regular or ongoing updates of the information sourced from various public platforms. Directorio Legislativo aimed to update their platform every six months, but internal capacity constraints and the unavailability of a streaming API has made this difficult. Constraints were also due to the absence of better and more standardised data across different sources.

For smaller-scale queries that require monitoring information over a period of time, automated alerts have been a useful way of supporting users in keeping up to date with any changes. For example, in Denmark, users can subscribe to email notifications to be informed of any change in a specific company’s ownership and control. This functionality is highly valued by research participants working in business monitoring and financial crime investigation. [76]

Use types, user profiles, and data-use journeys

While the research identified differences between use types, the needs they generate often overlap. In addition, user needs are not tied to specific professions. Specific sets of needs are highly dependent on the particular question a user is seeking to answer and questions can evolve along users’ journeys. Questions can cut across user profiles, meaning BO information can be used in the same way by different profiles of users. For example, users from a competition regulator, an NGO, an academic institution, a newspaper, and a law enforcement agency may all conduct large-scale processing to identify trends and to detect and mitigate risk. On the other hand, users from the media, customer-due-diligence teams in banks, NGOs, and tax and anti-corruption authorities may process BO information on a smaller scale to answer qualitative questions focusing on specific individuals or companies. Therefore, it is important to think beyond professions to better understand data use. Multiple users can form part of a single journey. For example, law enforcement officers have repeatedly highlighted the crucial role of civil society actors in meeting their objectives. ”We get many referrals from journalists and civil society organisations. It happens a lot. They are a great source of information. They may uncover offending we were not previously aware of” explains a research participant. [77]

While the section above takes a user’s question as the point of analysis, the research also found many examples of users asking a series of questions at different points in time. This research participant doing investigative work for a civil society organisation, explained:

“Sometimes when you are asset tracing, you hear about a person so you go looking for them in the data specifically, whereas other times you may be going through a whole database and look for suspicious things. We [call this] pole fishing and trawler fishing.” [78]

A similar point was mentioned by a research participant working for a tax authority, who explained that activities in their office could range from auditing specific people suspected of tax evasion, to identifying patterns and indicators of risk (see Box 4).

There is a large variety of questions users can seek to address and a small change in the question can significantly change user needs. Two questions may appear similar and yet create slightly different sets of needs in order to answer them (Box 6).

For example, the needs of a user asking What is the degree of ownership concentration in Denmark? would differ if they changed their question to What is the degree of ownership concentration in the Danish firms that have received public contracts? In the first question, the user would require ways of processing a large quantity of information as well as unique identifiers for individuals, but would not necessarily need multiple information sources. In the second question, the user would need to join records about companies to those in procurement data, requiring the same identifier to be used in both. In both of these questions, pseudonymised information would suffice. These queries may generate additional questions, such as What are the characteristics of companies where there is a high degree of ownership concentration? or Which politicians are involved in these companies? In the latter question, users would be interested in specific individuals and would not be able to answer the question with pseudonymised data. For example, when a journalist explored ownership concentration in Armenian media, they looked at Armenian television companies and were interested in identifying specific, powerful individuals with significant influence over the media landscape – in this case, they would need data that was not pseudonymised. [79]

As initial queries may generate additional, unforeseen questions associated with a new set of needs, which may be different from those users started with, data use can be seen as a multi-stage journey comprising multiple lines of inquiry. This may also take users back and forth between different questions and data sources, and makes BO data use journeys – and, therefore, associated user needs – difficult to predict (see Box 7).

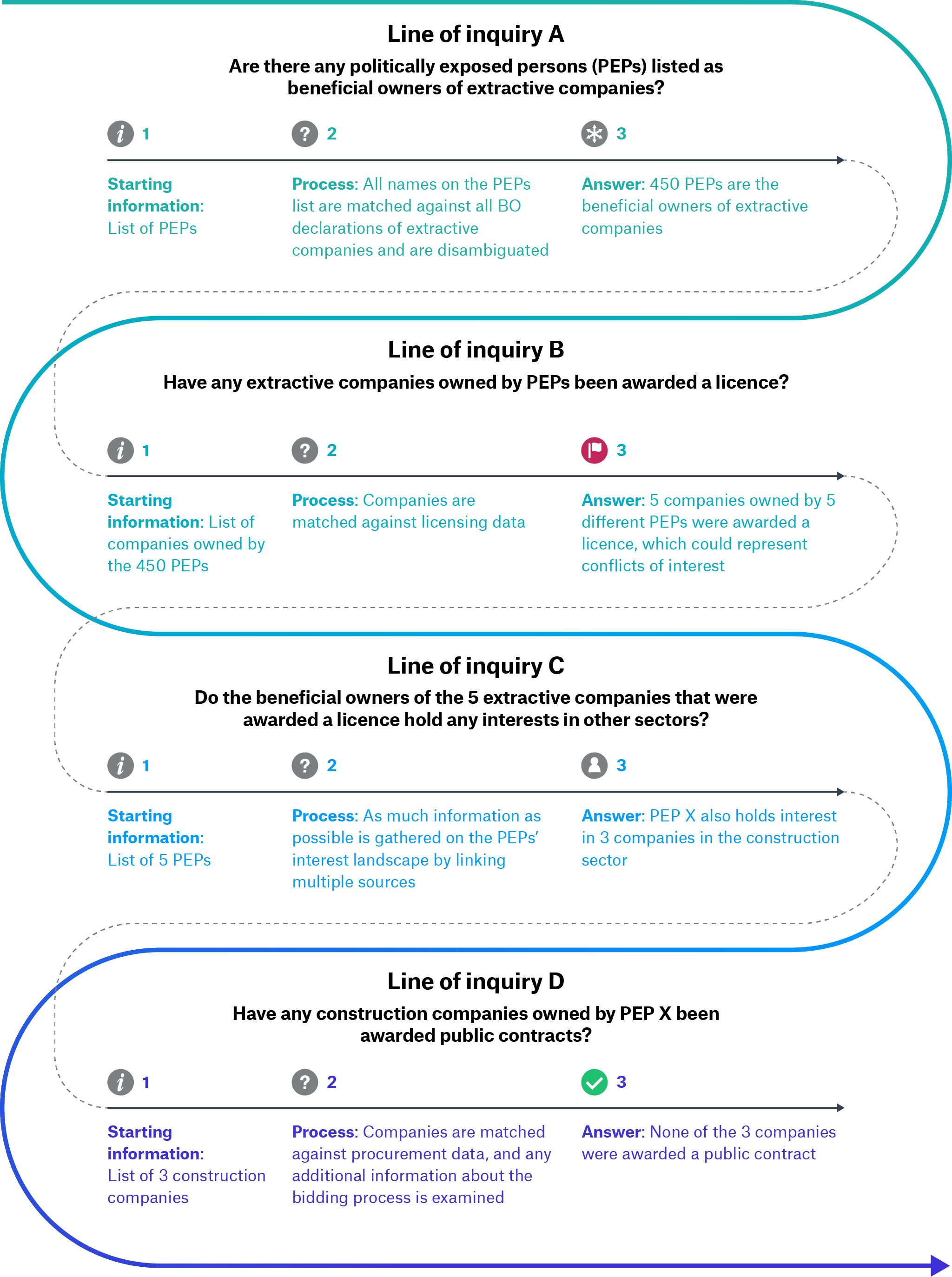

Box 7. A multi-stage journey of beneficial ownership data use

The first line of inquiry requires large-scale processing. The user may be generating statistics regarding PEPs involvement in extractive companies (quantitative), or identifying specific companies and PEPs to carry out further research on (qualitative). At this stage, they need to match individuals from a BO register to a PEPs list.

Having identified several hundreds of PEPs listed as beneficial owners of extractive companies on the BO registers, the user wants to see if any of these companies were awarded a mining licence and whether there were any conflicts of interest. [80] They will have to combine the BO information with information on mining licences. The time and effort this will take will depend on whether both information sources use a common identifier to, for example, establish that records relating to Company A listed in the BO register and records relating to Company A in the mining licences register are referring to the same entity.

Having identified red flags for potential conflicts of interest in the extractive sector, the user in this example wants to expand their analysis and check for any similar risks in other sectors (lines of inquiry C and D).

In practice, a user will almost never only need to access and process data in a single way. This suggests that, contrary to the second assumption of the research, defining categories of data users may not be necessary or helpful for making decisions about the content or structure of BO information. Developing a comprehensive view of aggregated user needs – beyond users’ professions – and seeking to address them may be more likely to inform access provisions that enable effective data use.

The majority of BO data users require flexibility to access and process data in ways that enable various use types. A limited amount of use types will be possible with more restrictive access and use provisions.

Research outcomes and avenues for future research

In summary, the research found that:

- There are different ways of using BO information (that is, use types) which cause specific user needs, as per the first assumption. The combination of the elements presented in this report (nature, scale, scope, and frequency) helps identify characteristics of users’ questions as well as determine use types and associated user needs to answer these questions.

- However, use types cut across different user profiles, confirming that categorising user needs solely based on user profiles is not useful to make decisions about access regimes. Additionally, data use is often a multistage journey involving multiple use types. Based on the variety and unpredictability of these journeys, users require flexibility to access and process data in ways that enable various use types. Therefore, and contrary to the second assumption, rather than developing a typology of use types as a basis for access, it is likely to be more impactful to build on the breadth of user needs outlined in this research to inform decisions about access.

These findings can inform the design and implementation of BOT reforms that enable the widest range of use types, and therefore may be more likely to lead to effective use and impact.

To date, the debate around access has primarily focused on whether registers should be publicly accessible or not, but this is a false dichotomy. [81] The research findings suggest that the narrative around access to BO information should be reframed by not just talking about “access to BO data for whom” but thinking through “access and processing of BO data to enable what”. This involves looking at the use types that are most likely to advance policy goals and the needs associated with these. By tying the processing of information to minimum needs and purpose, access provisions will be more in line with data-protection requirements.

Recognising that the majority of BO data users need a high degree of flexibility in how to access and process the data, this research also invites further work to develop recommendations on how to design access regimes that allow users to have more flexibility. Can this degree of flexibility be accommodated within contexts that allow public access to BO information? In the UK, this appears to be the case, but it is unlikely to be the case everywhere. For other contexts, safeguards may need to be put in place with respect to privacy and data protection to allow for flexible access and use, taking care that these safeguards do not unnecessarily prevent effective use. Jurisdictions should explore whether layered access systems can be designed on the basis of degrees of flexibility in how the information can be processed (e.g. APIs, searching by a range of criteria) in addition to the amount of information that can be accessed. If access on the basis of legitimate interest can be implemented well and provides high-quality, structured data with a wide range of attributes in bulk or via an API, it is possible that this may lead to more impact than where users have access to a public portal with limited search functionality. How this balance should be struck merits further research, with careful consideration of access provisions, data use, and impact.

To do this, Open Ownership will translate the user needs identified in this research to specific data features to help inform the design of the systems that collect, store, and share BO information. This will also allow implementers building beneficial ownership registries to assess whether their register enables data users to answer their questions, and thus contribute to policy goals.

Another key issue is how to address the challenges associated with accessing and processing BO information from multiple jurisdictions, including for law enforcement agencies, for example. The role of international and regional data-sharing agreements as well as other potential solutions merits further exploration.

This research has raised a number of questions which provide avenues for potential future research. For example:

- Data intermediaries are currently solving both basic usability issues and providing advanced functionalities and tools to allow more advanced analyses. They fulfil a critical role in the BO data-use ecosystem. This raises important questions on the technical capacities and cost effectiveness for governments developing their own data-use tools. These questions are also relevant for the development of APIs, which many respondents flagged as a key feature to support effective data use. How can registrars with lower technical and financial capacity effectively address user needs? It also raises questions on whether the cost of commercial providers may lead to inequalities in data use. Given their central role in enabling end users to use data, it also raises questions regarding access and data-processing provision for intermediary users. This calls for further research on the potential role of public-private partnerships in advancing BO data use.

- BO data use typically involves understanding relationships between subjects across different information sources and jurisdictions. As this is currently difficult for many research participants, many value platforms that centralise information from various sources and help make ownership networks understandable. Currently, asset registers usually do not contain sufficient information to easily establish whether records in those registers refer to the same subject as records in BO registers. This could mandate defining a common set of minimum information to be collected by domestic asset registers. [82] It is also worth exploring how shareholder information can be used as a more reliable source of information to improve understanding of ownership networks, lower compliance burdens, and verify BO declarations.

- Finally, this research lays the basis for starting to systematically and proactively measure how various policy and systems design decisions influence the effectiveness of data use and ultimately the impact of BOT reforms. More work is needed to define a set of indicators to support this measurement exercise.

Footnotes

[7] Open Ownership, Open Ownership Principles.

[8] Interview #003.

[9] Interview #018.

[10] “About OCCRP Aleph”, OCCRP, Aleph, n.d., https://aleph.occrp.org/pages/about.

[11] Interview #028; interview #007.

[12] Interview #022.

[13] Interview #022; interview #029. In the European context, the Network of Experts on Beneficial Ownership Transparency (NEBOT) provided an overview of various domestic BO registers which also pointed to challenges posed by limited search functionalities. See: Adriana Fraiha Granjo, Maíra Martini, and Gabriel Sipos, NEBOT Paper Five – Beneficial ownership registers in the EU: Progress so far and the way forward (European Commission, Directorate-General for Financial Stability, Financial Services and Capital Markets Union – Publications Office of the European Union, 2023), https://images.transparencycdn.org/images/NEBOT-Paper-5.pdf.

[14] Interview #012.

[15] Interview #025.

[16] Interview #013.

[17] Kadie Armstrong, Building an auditable record of beneficial ownership (Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative (EITI) and Open Ownership, 2022), https://www.openownership.org/en/publications/building-an-auditable-record-of-beneficial-ownership/.

[18] Interview #023.

[19] Interview #013; interview #012. See: Julie Rialet, Use and impact of public beneficial ownership registers: Denmark (Open Ownership, 2023), https://www.openownership.org/en/publications/use-and-impact-of-public-beneficial-ownership-registers-denmark/.

[20] Interview #025.

[21] User testing interview with Siiri Grabbi, Sanctions/Countering the Financing of Terrorism (CFT) Officer, Coop Pank AS, Estonia, 29 October 2024. See: Miranda Evans, “Lessons from building a prototype single-search tool for beneficial ownership registers”, Open Ownership, 7 March 2025, https://www.openownership.org/en/blog/lessons-from-building-a-prototype-single-search-tool-for-beneficial-ownership-registers/.

[22] Evans, “Lessons from building a prototype single-search tool for beneficial ownership registers”.

[23] Interview #034.

[24] Competition and Markets Authority (CMA), The State of UK Competition (CMA, 2022), https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/627e6cf6d3bf7f052d33b0ae/State_of_Competition.pdf.

[25] CMA, “Appendix A: Concentration”, in State of UK Competition, (CMA, 2022), para. 89, https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/626ab6c4d3bf7f0e7f9d5a9b/220426_Annex_-State_of_Competition_Appendices_FINAL.pdf.

[26] Kadie Armstrong and Stephen Abbott Pugh, Using reliable identifiers for corporate vehicles in beneficial ownership data (EITI and Open Ownership, 2023), https://www.openownership.org/en/publications/using-reliable-identifiers-for-corporate-vehicles-in-beneficial-ownership-data/.

[27] Alanna Markle, Sufficiently detailed beneficial ownership information (Open Ownership, 2025), https://www.openownership.org/en/publications/sufficiently-detailed-beneficial-ownership-information/.

[28] Bank for International Settlements (BIS), Report to the G20: Harmonised ISO 20022 data requirements for enhancing cross-border payments (BIS, 2023), https://www.bis.org/cpmi/publ/d218.pdf.

[29] User testing interview with an independent financial crime specialist, Denmark, 11 November 2024. See: Evans, “Lessons from building a prototype single-search tool for beneficial ownership registers”.

[30] Interview with Mihály Fazekas, Associate Professor at Central European University and Founder of Government Transparency Institute; Antoninia Volkotrub, Financial Analyst at Anti-Corruption Action Center, Ukraine; and Irene Tello Arista, Co-Chair of Action4Justice and PhD researcher at Central European University, 1 December 2023.

[31] Centre for Finance, Innovation and Technology (CFIT), Fighting Economic Crime Through Enhanced Verification: Interim paper from CFIT’s second coalition (CFIT, 2024), https://cfit.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/CFIT-Economic-Crime-Coalition-Interim-White-Paper-1.pdf.

[32] “European Digital Identity”, European Commission, n.d., https://commission.europa.eu/strategy-and-policy/priorities-2019-2024/europe-fit-digital-age/european-digital-identity_en.

[33] Interview #019.

[34] Interview #019.

[35] Interview #018.

[36] Interview #023.

[37] Interview #013.

[38] Interview #025.

[39] Interview #019.

[40] For more information, see: Sadaf Lakhani, The use of beneficial ownership data by private entities (Open Ownership, 2022), https://www.openownership.org/en/publications/the-use-of-beneficial-ownership-data-by-private-entities/.

[41] Interview #020; interview #012.

[42] Interview #029.

[43] Interview #027; interview #020.

[44] Interview #012; interview #027.

[45] Interview #034.

[46] Sara Brimbeuf, Maíra Martini, Florian Hollenbach, and David Szakonyi, Behind A Wall: Investigating Company and Real Estate Ownership in France (Transparency International France and Anti-Corruption Data Collective, 2023), https://images.transparencycdn.org/images/2023-Report-Behind-a-Wall-English.pdf.

[47] Rialet, “Closing the loop”.

[48] User testing interview with Ben Cowdock, Senior Investigative Lead, Transparency International UK, 27 November 2024. See: Evans, “Lessons from building a prototype single-search tool for beneficial ownership registers”.

[49] Interview #021.

[50] Interview #020; interview #029; interview #026.

[51] “Regulatory penalties for global financial institutions surge 31% in H1 2024”, Fenergo, 14 August 2024, https://resources.fenergo.com/newsroom/regulatory-penalties-for-global-financial-institutions-surge-31-in-h1-2024; FATF, Recommendation 10.3 and 29.3 in Methodology for Assessing Compliance with the FATF Recommendations and the Effectiveness of AML/CFT Systems (FATF, updated 2023), 43, 79, https://www.fatf-gafi.org/content/dam/fatf-gafi/methodology/FATF%20Methodology%2022%20Feb%202013.pdf.coredownload.pdf; Egmont Group, Egmont Group Of Financial Intelligence Units: Principles For Information Exchange Between Financial Intelligence Units (Egmont Group, updated 2022), https://egmontgroup.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/10/2.-Principles-Information-Exchange-Revised-May-2022-01.pdf.

[52] Interview #013.

[53] Interview #028.

[54] Interview #002.

[55] Open Ownership, “Screening mining and petroleum licences with beneficial ownership information”, technical capacity-building workshop, Ghana, 8-12 July 2024; interview #010.

[56] Interview #36. See case study on BO in Denmark: Rialet, Use and impact of public beneficial ownership registers: Denmark, 10.

[57] Interview #021.

[58] Interview #016.

[59] Interview #033.

[60] Brimbeuf et al., Behind A Wall.

[61] Irene Tello Arista, Mihály Fazekas, and Antonina Volkotrub, Using beneficial ownership data for large-scale risk assessment in public procurement: The example of 6 European countries (Government Transparency Institute, 2024), https://www.govtransparency.eu/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Arista-Fazekas-Volkotrub_BO-CRI_GTI_WP_2024.pdf.

[62] Interview #024.

[63] Interview #021.

[64] Interview #003.

[65] User testing interview with Ben Cowdock, Senior Investigation Lead, Transparency International, UK, 27 November 2024. See: Evans, “Lessons from building a prototype single-search tool for beneficial ownership registers”.

[66] Interview #003.

[67] Interview #004.

[68] Interview #012.

[69] Adam Travis, “The Organization of Neglect: Limited Liability Companies and Housing Disinvestment”, American Sociological Review 84, no. 1 (2019): 142-170, https://doi.org/10.1177/0003122418821339; Rachel Holliday Smith, “More Money? Pushy Landlord? Your Emergency Rental Assistance Program (ERAP) Questions Answered”, The City, 7 March 2022, https://www.thecity.nyc/2022/03/07/new-york-city-landlord-emergency-rental-assistance-program-erap-questions-answered/.

[70] This type of question is useful to assess the quality of the data and suggest any areas for improvement to the authorities implementing BOT reforms. Open Ownership has been carrying out and supporting this type of analysis. See, for example, this upcoming publication in collaboration with the Tax Justice Network: Maria Jofre and Andres Knobel, Insights from the United Kingdom People with significant control register (Open Ownership and Tax Justice Network, forthcoming in 2025); FATF, Report on the State of Effectiveness and Compliance with FATF Standards (FATF, 2022), 31, https://www.fatf-gafi.org/content/dam/fatf-gafi/reports/Report-on-the-State-of-Effectiveness-Compliance-with-FATF-Standards.pdf.coredownload.pdf.

[71] Egmont Group, “Case 3: Nigeria’s former oil minister charged after $20 billion goes missing from petroleum agency —Nigeria FIU”, in Best Egmont Cases: Financial Analysis Cases 2021–2023 (Egmont Group, 2024), 15–20, https://egmontgroup.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/09/EGMONT_2021-2023-BECA-III_FINAL.pdf.

[72] Delgermaa Boldbaatar (Mongolian Data Club) and Erdenechimeg Dashdorj (Open Society Forum), “Digging out data to shine a light on public buying in Mongolia”, Open Contracting Partnership, 11 October 2023, https://www.open-contracting.org/2023/10/11/digging-out-data-to-shine-a-light-on-public-buying-in-mongolia/.

[73] Ц.Мягмарбаяр, Б.Энхзаяа, Ц.Энхдулам, and А.Маралмаа,“Тэнцүү олгосон нэртэй с зөвшөөрлийн ард сингапур, хятад ноёд туйлж байна”, Polit.mn, 28 April 2023, https://www.polit.mn/a/101369.

[74] Б.Ариунзаяа, “МЭДЛЭГИЙН ГРАФ: Сонгуулийн уралдаанд №1-т сойсон Г.Лувсанжамцын ‘шүдийг шинжье’”, Datastory, 23 June 2024, http://datastory.mn/article/46; Б.Ариунзаяа, “Эрчим хүчний сэргэлтийн илгээлтийн эзэн М.Энхцэцэгийн авсан тендэр ₮16.3 тэрбум”, Datastory, 27 June 2024, http://datastory.mn/article/47.

[75] Joining the Dots, home page, Directorio Legislativo, n.d., https://peps.directoriolegislativo.org/.

[76] Rialet, Use and impact of public beneficial ownership registers: Denmark, 10.

[77] Interview #021.

[78] Interview #023.

[79] Mariam Tashchyan, “Ովքե՞ր են հետուստաընկերությունների իրական շահառուները. հայտարարագրվածն ու «դուրս մնացածը»”, CivilNet, 27 December 2022, https://www.civilnet.am/news/687511/.

[80] For example, the Anti-Corruption Action Centre (AntAC) carried out this type of analysis to identify specific PEPs that ultimately owned a large proportion of permits in the extractive sector in Ukraine. See: AntAC, Who owns oil and gas fields of Ukraine? – Analytical report. Part 1 (AntAC, 2018), https://antac.org.ua/en/news/11-politically-exposed-persons-own-a-quarter-of-all-permits-for-extraction-of-oil-and-gas-in-ukraine-report/.

[81] Tymon Kiepe, “Striking a balance: Towards a more nuanced conversation about access to beneficial ownership information”, Open Ownership, 18 October 2023, https://www.openownership.org/en/blog/striking-a-balance-towards-a-more-nuanced-conversation-about-access-to-beneficial-ownership-information/.

[82] Structured data refers to information that is highly organised according to a predefined model. See: Tymon Kiepe, “Solving the international information puzzle of beneficial ownership transparency”, Open Ownership, 17 June 2024, https://www.openownership.org/en/blog/solving-the-international-information-puzzle-of-beneficial-ownership-transparency/.