Using beneficial ownership information in fisheries governance

Leveraging ongoing beneficial ownership transparency efforts to improve fisheries governance

To ensure that the implementation of central BO registers leads to useful and usable data for a wide range of users to achieve various policy objectives, it is critical that these users are consulted and included in discussions from the outset. Therefore, fisheries agencies and vessel registries as well as fishing directorates, tax and customs authorities, maritime and coastguard agencies, and RFMOs should be consulted and involved in BOT implementation. Public consultations should seek to include those working in or on the fisheries sector. In addition to ensuring usability, governments should ensure the data is being used.

Operationalising the use of BO data in fisheries – and specifically leveraging ongoing efforts to implement BOT – brings a number of policy, legal, and technical considerations. It requires making decisions about how to define the BO of assets; which corporate vehicles and assets are covered; how and when to collect BO data; and how to provide access, to whom, and in which format.

These will all have an impact on which of the use cases can be used, and which potential loopholes remain. How and in what format data is collected, stored, and shared will affect its ability to be linked to other datasets, which is critical when governments want to leverage existing BOT efforts. The following section outlines some key considerations for implementers, and draws from the Open Ownership Principles for effective beneficial ownership disclosure. [161]

Defining the beneficial ownership of corporate vehicles and assets

BO is a substantive concept that captures the natural persons who ultimately own, control, or derive benefit from an asset. As previously mentioned, the majority of countries have implemented – or are in the process of implementing – BO registers for corporate vehicles. These are predominantly focused on legal entities, broadly defined as corporate vehicles that have a separate legal personality, such as a company. This means they have many of the legal rights and obligations that individuals have, including the ability to own assets, sign contracts, and acquire debt. Some jurisdictions also require the registration and BO disclosure of legal arrangements. Legal arrangements exist between two or more parties and are a type of corporate vehicle that do not have a separate personality, but can sometimes operate like a business in many of the same ways a legal entity can. The most common legal arrangement is a trust. All definitions in international standards predominantly focus on applying beneficial ownership as a substantive concept to legal entities and arrangements.

Historically, however, definitions have mostly focused on defining the beneficial ownership of limited liability companies. As the concept of beneficial ownership has been extended to an increasing number of corporate vehicle types and assets, some established legal definitions have fallen short of achieving their purpose. Many BO definitions for legal entities are proving unsuitable for capturing relevant information on the ownership and control of certain types of corporate vehicles, including SOEs, publicly listed companies, and investment funds. [162] Individuals can own, control, and benefit from different corporate vehicles in different ways. For example, share ownership and the application of a percentage threshold constituting beneficial ownership may not be relevant for corporate vehicles without legal personalities, such as trusts. Legal definitions need to be reconsidered to ensure they sufficiently capture how individuals can own, control, and benefit from specific corporate vehicles and assets.

Fisheries governance involves not just corporate vehicles, but also assets like fishing licences and vessels. Individuals can own, control and benefit from assets in different ways which are highly specific to both the asset and the national laws that govern it. The beneficial ownership of assets is an emerging field, and it has primarily focused on land and real estate. For example, in 2019, the Canadian province of British Columbia (BC) started implementing a register of the beneficial ownership of land. The definition includes aspects like the right to occupy land under a lease, which has a term of more than ten years, or the right under an agreement for sale to occupy land. [163]

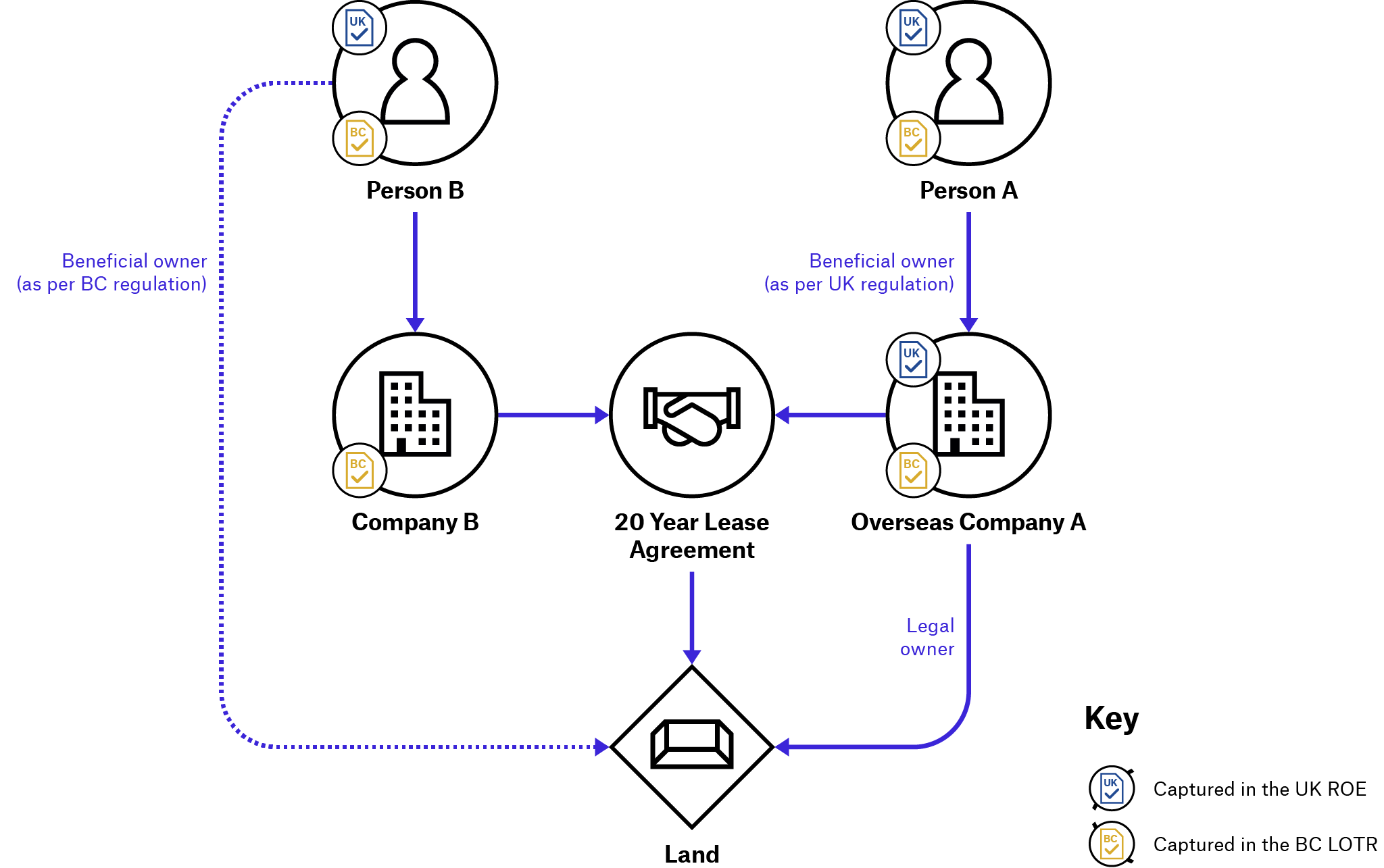

In contrast, the UK implemented a register of overseas entities that own UK property or land. [164] There is a critical difference between these registers, as the former concerns the beneficial ownership of the underlying asset, and the latter concerns the beneficial ownership of the legal owners of the asset (see Figure 3). In the latter case, an individual who uses a corporate service provider to acquire property on their behalf through a contract or agreement would not be subject to disclosure, as that individual would not be a beneficial owner of the corporate service provider, but would be a beneficial owner of the asset. This is particularly relevant for vessels in which a range of parties often have an interest beyond the legal owner, including those who finance, lease, and operate the vessel. Some commercial BO data providers do cover assets such as vessels, but it is reasonable to assume these face the same challenges as commercial databases of corporate vehicles, and that governments are better placed to collect, collate, and verify the information. [165]

Figure 3. Difference in scope between the United Kingdom Register of Overseas Entities and the British Columbia Land Ownership Transparency Register

Both the UK Register of Overseas Entities (ROE) and the BC Land Ownership Transparency Register (LOTR) would collect information on Overseas Company A as a registered owner, including its beneficial owner, Person A. Only the LOTR would capture information on Person B, who has an indirect interest in the land through a lease agreement with Company B, making Person B a beneficial owner of the land under BC legislation. By contrast, the ROE would only capture information about the beneficial owners (as per UK legislation) of the legal owner of the land, where this legal owner is an overseas company.

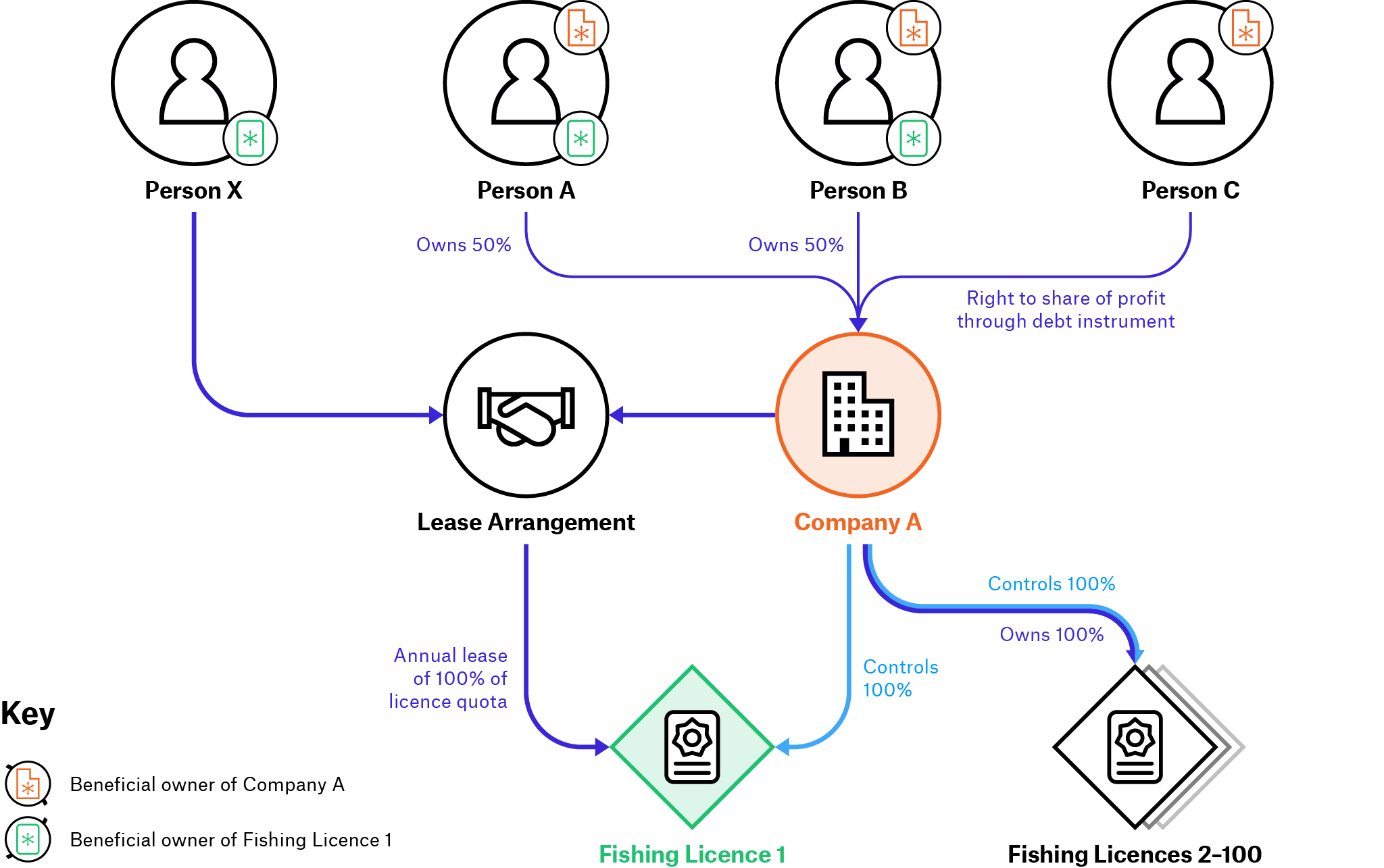

This particular issue in fisheries was highlighted in a parliamentary committee hearing in Canada, where the government tried to establish who benefits from fishing licences by asking licence owners who their beneficial owners are. [166] As discussed in the hearing, the survey could not comprehensively cover who benefits from licences focusing solely on the beneficial ownership of licence holders due to the prevalence of leasing (see Figure 4). [167]

Figure 4. Example demonstrating the difference between the beneficial ownership of a corporate vehicle and its underlying asset

Company A owns Fishing Licence 1. It has entered into a lease arrangement with Person X to fish 100% of the quota rights of the licence. Person X is a beneficial owner of Fishing Licence 1. Persons A and B are beneficial owners of Company A due to their each owning 50% of its shares. They are also beneficial owners of Fishing Licence 1, as they each indirectly control 100% of the licence. Person C is a beneficial owner of Company A due to their right to a share of the profit through a debt instrument. However, Person C has no indirect significant ownership, control, nor will necessarily derive significant benefit from Fishing Licence 1 if the leasing fee forms only a small part of the company’s overall profits. Therefore, Person C is not a beneficial owner of Fishing Licence 1. Persons A, B, and C would be captured on a central BO register for companies.

Beneficial ownership of corporate vehicles that own assets

An approach that would leverage current reform efforts and require the least additional effort would be to ensure registers capture various parties that hold specific, defined interests in an asset. For a fishing licence, this would be the licence holder, or whoever the licence is leased to. This information can then be combined with BO information of corporate vehicles so that where a corporate vehicle is one of these parties, their beneficial owners will be known. This may not equate to a comprehensive overview of individuals who are beneficial owners of the asset due to the aforementioned reasons – for example, a party may hold an interest that is not captured. However, the information available would be a significant improvement from the current state of play, and it could be sufficient for many, if not most, of the use cases discussed above, particularly for investigations and oversight of fisheries tenure, where the main use case for the information is to establish links between various parties. Whether it is or not may depend on the national make-up of licence ownership. For example, a government survey conducted with licence holders in Canada found that:

Over 97% of surveyed licence holders employ a simple corporate structure, in which the licence holder is either an individual themselves, or a company that is owned by one or more individuals or wholly-owned companies. Complex corporate entities with multiple indirect owners make up a very small proportion (3%) of commercial licence holders. [168]

Focusing on the beneficial ownership of corporate vehicles that own the licence or the vessel would also capitalise on whole-of-government efforts to ensure the accuracy of the data on the beneficial ownership of corporate vehicles through verification. It could also be complemented by additional measures, such as requiring the owner of the vessel and the licence to be the same, and requiring fishing rights to be tied to specific vessels until the vessel ownership changes. Governments may also consider introducing lower thresholds for companies involved in the fisheries sector, as has been done in a number of countries for higher-risk sectors. [169]

Beneficial ownership of assets

A solution that seeks to go beyond this could involve enumerating a range of relevant interests that would constitute beneficial ownership of the asset, including how an individual could beneficially own an underlying asset through a corporate vehicle. This can become quite complicated when considering the full range of interests a party can have in an asset, and how this may vary by country. For example, in the case of fishing licences, these interests can include – at their simplest – leasing, but also various other indirect licence arrangements and economic relationships, such as loans and controlling agreements that may exist between parties associated with a licence or the registered vessel owner in a vessel-based licence. [170]

The full list of these interests will depend on country-specific fisheries tenure legislation. For this reason, whilst it may provide a more comprehensive overview of the ownership and control of those assets, the implementation of the beneficial ownership of assets may lead to a proliferation of different definitions globally and even higher challenges with standardisation than those that exist for corporate vehicles. Domestically, it may lead to different government departments setting up their own efforts to define and collect BO information, leading to regulatory burden and ambiguity. For example, in the Seychelles, a beneficial owner is defined in the 2020 Beneficial Ownership Act covering legal entities and arrangements:

“beneficial owner” means one or more natural persons who ultimately own or control a customer or the natural person or persons on whose behalf a transaction is being conducted and includes those natural persons who exercise ultimate effective control over a legal [entity] or a legal arrangement. [171]

There is another definition of beneficial owner in the 2023 Fisheries and Aquaculture Bill, covering both vessels and legal entities and arrangements:

“beneficial owner” means the natural person(s) who ultimately owns or controls a vessel or the natural person(s) on whose behalf a transaction is being conducted, and includes those persons who exercise ultimate effective control over a legal [entity] or arrangement. [172]

This may cause ambiguity. The legislation could instead have a single, unified definition of beneficial ownership, explaining in subsidiary legislation what this means when applied to corporate vehicles, and separately when applied to vessels. The legislation does not spell out what constitutes ownership and control of the asset in question.

Assuming a government has implemented a central register for the beneficial ownership of corporate vehicles, it should consider which types of interests in fishing rights and vessels it seeks to collect information on. It should then assess to what extent this information would overlap with BO information already held, where these interests are held by a corporate vehicle. Implementers should appreciate the difference between the beneficial ownership of a corporate vehicle and the beneficial ownership of an asset. If focusing on the former, they should consider what loopholes remain, and potentially address those through complementary regulations.

Coverage

Implementers will also have to consider which corporate vehicles they will need BO information about, and which of these will already be covered by existing legislation. A key challenge for fisheries is the involvement of non-domestic companies, as most central BO registers implemented to date are national in scope. For example, foreign-owned operations represented 70% of the commercial fishing fleet in the Seychelles. [173] The FATF requires countries to implement measures to address risk including those posed by corporate vehicles with a sufficient link to a jurisdiction. [174] There are some early examples of these, including the UK ROE. Moreover, there are considerable challenges in verifying the accuracy of BO information from non-domestic corporate vehicles.

Evidence also shows that due to national variances in corporate vehicles, how non-domestic corporate vehicles are owned and controlled may be poorly understood. [175] As an increasing number of jurisdictions collect BO information on domestic corporate vehicles, efficient international exchange of information on domestic corporate vehicles may serve as a more reliable alternative to the collection of information on foreign corporate vehicles in the longer term. [176] However, this requires implementation internationally to be done to a certain policy, legal, and technical standard, especially if the BO data is to be interoperable and readily used in domestic systems, and for countries to be willing to exchange information for fisheries-related purposes. [177] Until significant global progress is made on this, many countries will likely still opt to collect BO information on foreign corporate vehicles. [178] Where governments choose to do so for fisheries purposes, the authority responsible for the central BO register for domestic corporate vehicles may be better placed – than, for example, the fishing licensing agency – to also collect foreign corporate vehicles, as it may be more likely to have the required knowledge, skills, and resources.

Closely related to this is the consideration of the use of certain corporate vehicles which may be common in fisheries and not be subject to specific disclosure requirements, such as JVs. In fisheries, JVs have been used to feign local involvement, whilst in reality a foreign entity fully owns, controls, and benefits from the venture. [179] In these cases, implementers should consider additional disclosure requirements in licence applications, both in terms of the licence applicant and the owner of the vessel in question. [180]

Some countries impose requirements for the licence holder to be a national or domestic company (such as Ghana), or for the vessels to be domestically registered and flagged (such as Argentina), which, in theory, can help avoid this challenge. [181] However, as discussed in the case of Ghana above, and through the use of structures such as JVs, there is a risk some may attempt to circumvent these requirements.

Data collection

Broadly, it is best practice for governments not to hold potentially conflicting information on the same corporate vehicle. Therefore, a central authority, which has the appropriate experience, skills, and knowledge, should hold the information on all domestic corporate vehicles according to a unified legal definition, and other government agencies should use and update the information in this register. Many central registers leverage information held by various government agencies to ensure the accuracy of BO declarations. [182] Separate government agencies collecting their own information would not benefit from this, and it may lead to an unnecessary regulatory burden.

Differing legal definitions of beneficial ownership could lead to regulatory ambiguity. This may create a situation where different government agencies hold conflicting information on a single corporate vehicle without knowing whether this is due to one being false or due to different definitions and disclosure requirements, making it challenging to establish accuracy. To illustrate, many countries already collect BO information as part of licence applications but face challenges with verification. Very often, either the legal owner or the name of a local agent is disclosed.

Where fishing licensing and vessel registration agencies decide to use corporate vehicles’ BO information, they can collect this information themselves. However, in this case, it is critical that governments ensure they are using the same legal definition and data collection forms, and compare and consolidate any information collected with the central register. Any discrepancy may be an indication of attempted wrongdoing. Alternatively, government agencies can require an attestation that this information is up to date in the central register, or require a certified extract from the central register to be attached to the application, as is done in Jersey. [183] This extract can then be checked against the central records.

Where fishing licensing and vessel registration agencies are aiming to create registers of beneficial owners of the assets themselves, there may be overlap with the information collected under a central BO register for corporate vehicles. This information should be checked against any information held in the central register. Both fishing licensing and vessel registration agencies should seek to collect information in a structured way, including reliable identifiers for the corporate vehicles, licences, and vessels involved. [184]

Where the body using the information is an RFMO, it may rely on information collected by its member states, meaning access to this information is critical, as covered in the following section. It may also have to work with differing implementation standards, such as legal definitions and methods of structuring data. Therefore, RFMOs and other international and multilateral bodies should require member states to adopt certain implementation standards, particularly with respect to legal definitions, data structure, and access. RFMOs may be well placed to serve as platforms for sharing domestic BO information regionally. Where RFMOs opt to collect information according to their own definitions and standards, similar challenges as above exist, particularly with respect to verification.

Data structure, format, and access

Authorities implementing central BO registers should ensure information is useful and usable by all relevant actors. To do so, information should be easily accessible by relevant data users in a structured format so it can be readily combined with other datasets – for example, licence, quota, vessel, and PEP registers.

There has been much debate about balancing the access to BO information with the right to privacy. Each jurisdiction should evaluate how they can ensure that these actors have access to the specific information they need and, to the extent possible, maximise privacy protection without overly compromising on data usability. [185] Ensuring fisheries sector governance, oversight, and accountability are included in the stated BOT policy objectives can help provide a legal basis for access. This should go beyond the aim of fighting crime as, for example, small-scale fishing associations are also relevant potential data users for the purposes of identifying harmful market concentration.

At the minimum, fishing directorates, fishing licensing, vessel registration, maritime and coastguard authorities, and customs and tax authorities should have direct access to the data. In order to realise most of the use cases above, non-governmental parties, including those working in the fisheries sector, will need access to licensing and vessel ownership information as well as BO information of the corporate vehicles involved. Where information is not made publicly available but on the basis of demonstrating a legitimate interest, this should consider fisheries governance more broadly, rather than just countering crime. Non-governmental parties working in or on the fisheries sector should be considered to have this by default.

To realise many of the use cases above – including, for example, automated red flagging – users will need to access the data in bulk format and be able to combine different datasets. This will require information to be structured and include reliable identifiers for the corporate vehicles, licences, and vessels. [186] For corporate vehicles, this should include either international identifiers, such as the Legal Entity Identifier (LEI), or information on the jurisdiction of incorporation, along with a domestic identifier. [187] This does, however, require BO information for the corporate vehicles in question to be accessible in their jurisdiction of registration. Some use cases may also require matching individuals between different datasets, for example, BO and PEP registers, which may need to rely on secondary personal identifiers (e.g. date of birth, nationalities) when combining information from different jurisdictions. Specific access provisions (e.g. which data is available, in what format, and by who) should be informed by the use cases themselves. Box 3 highlights some of the challenges with combining licence and BO data.

Complementary measures

A number of complementary measures could help leverage existing BOT efforts, particularly where those are primarily aimed at AML. These may facilitate both intranational and international data sharing. Firstly, all fisheries crimes, including those committed overseas, could be added to the list of predicate offences for money laundering, particularly where there is crime convergence with other organised crime. A similar approach has been suggested for environmental crimes. [188] Whilst this may primarily aid law enforcement prosecuting crimes, it may also help with access to non-domestic ownership information. Secondly, fisheries licensing, vessel registration, and maritime and coastguard authorities could be given specific AML responsibilities and be considered competent authorities. This would enable data sharing between these agencies and FIUs, as well as enabling bilateral FIU-to-FIU BO data sharing for foreign companies and vessels. All these agencies should have a good understanding of fisheries-related crimes and the use of corporate vehicles.

Footnotes

[161] Open Ownership, Open Ownership Principles.

[162] See: Emma Howard and Stephen Abbott Pugh, Defining and capturing data on the ownership and control of state-owned enterprises (s.l.: Open Ownership, 2023), https://www.openownership.org/en/publications/defining-and-capturing-data-on-the-ownership-and-control-of-state-owned-enterprises/; Ramandeep Kaur Chhina and Alanna Markle, Defining and capturing information on the beneficial ownership of investment funds (s.l.: Open Ownership, 2024), https://www.openownership.org/en/publications/defining-and-capturing-information-on-the-beneficial-ownership-of-investment-funds; Ramandeep Kaur Chhina and Tymon Kiepe, Defining and capturing information on the beneficial ownership of listed companies (s.l.: Open Ownership, 2024), https://www.openownership.org/en/publications/defining-and-capturing-information-on-the-beneficial-ownership-of-listed-companies.

[163] LOTA, Chapter 23, Section 2.

[164] Companies House, UK Government, “Register an overseas entity and its beneficial owners”, updated 29 January 2024, https://www.gov.uk/guidance/register-an-overseas-entity.

[165] Most commercial BO databases for corporate vehicles ultimately rely on government registers for their information. For more information, see: Sadaf Lakhani, The use of beneficial ownership data by private entities (s.l. Open Ownership, 2022), https://www.openownership.org/en/publications/the-use-of-beneficial-ownership-data-by-private-entities/.

[166] Fisheries and Oceans Canada (DFO), Government of Canada, “Beneficial Ownership Survey”, updated 22 September 2023, https://www.dfo-mpo.gc.ca/fisheries-peches/commercial-commerciale/bos-spe-eng.html.

[167] Canada House of Commons, “Standing Committee on Fisheries and Oceans – Number 066”, 6.

[168] Government of Canada, Department of Fisheries and Oceans, “2022 Beneficial Ownership Survey results”, September 2023, https://www.dfo-mpo.gc.ca/about-notre-sujet/publications/fisheries-peches/bos-spe/index-eng.html.

[169] Some jurisdictions have defined the beneficial ownership of a corporate vehicle using a lower threshold for share ownership and voting rights for high-risk sectors, notably the extractive industries. For example, Ghana applies a 5% threshold to high-risk sectors – including the extractive industries, banking, insurance, and gambling – and 20% for all other sectors. (Regulation 54 of Ghana’s draft Companies Regulations.)

[170] Silver and Stoll, “How do commercial fishing licences relate to access?”.

[171] Republic of Seychelles, “Beneficial Ownership Act, 2020”, 2020, https://seylii.org/akn/sc/act/2020/4/eng@2020-03-06.

[172] Republic of Seychelles, “Fisheries and Aquaculture Bill 2023 (Bill No. 23 of 2023) Explanatory Statement of the Objects of and Reasons for the Bill”, Supplement to Official Gazette, 2023, https://www.gazette.sc/sites/default/files/2023-11/Bill%2023%202023%20-%20Fisheries%20and%20Aquaculture%20Bill%202023.pdf.

[173] “Industrial fishing”, Seychelles Fishing Authority, 2021, https://www.sfa.sc/fisheries/industrial.

[174] FATF, International Standards on Combating Money Laundering and the Financing of Terrorism and Proliferation: The FATF Recommendations (Paris: FATF, 2012-23), 93, https://www.fatf-gafi.org/content/dam/fatf-gafi/recommendations/FATF%20Recommendations%202012.pdf.coredownload.inline.pdf.

[175] Alanna Markle, Coverage of corporate vehicles in beneficial ownership disclosure regimes (s.l.: Open Ownership, 2023), 8-9, https://www.openownership.org/en/publications/coverage-of-corporate-vehicles-in-beneficial-ownership-disclosure-regimes/.

[176] Open Ownership, “Open Ownership map”; Alanna Markle, Coverage of corporate vehicles in beneficial ownership disclosure regimes, 10.

[177] Jack Lord and Tymon Kiepe, Structured and interoperable beneficial ownership data (s.l.: Open Ownership, 2022), 9, 12, https://www.openownership.org/en/publications/structured-and-interoperable-beneficial-ownership-data/.

[178] For example, the 2024 EU Anti-Money Laundering Package includes requirements for EU member states to collect information on non-EU corporate vehicles that own real estate or do business in the EU in their central BO register. Council of the EU, “Proposal for a Regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council on the prevention of the use of the financial system for the purposes of money laundering or terrorist financing - Confirmation of the final compromise text with a view of agreement”, 13 February 2024, 259-263, https://data.consilium.europa.eu/doc/document/ST-6220-2024-REV-1/en/pdf; “Anti-money laundering: Council and Parliament strike deal on stricter rules”, Council of the EU, Press Release, 18 January 2024, https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/press/press-releases/2024/01/18/anti-money-laundering-council-and-parliament-strike-deal-on-stricter-rules/.

[179] EJF, Off the Hook: How flags of convenience let illegal fishing go unpunished (London: EJF, 2020), https://ejfoundation.org/resources/downloads/EJF-report-FoC-flags-of-convenience-2020.pdf.

[180] Joint ventures are also common in the extractive industries. The 2023 EITI Standard requires each entity within the venture to disclose its beneficial owner. In case of a foreign entity, this may require access to a foreign register or collection of BO information of a non-domestic entity. See: EITI, EITI Standard 2023 (Oslo: EITI, 2023), https://eiti.org/sites/default/files/2023-06/2023%20EITI%20Standard.pdf.

[181] “Solicitar permisos de pesca de gran altura”, Government of Argentina, Ministerio de Economía, Secretaría de Agricultura, Ganadería y Pesca, n.d., https://www.argentina.gob.ar/solicitar-permisos-de-pesca-de-gran-altura.

[182] See: Open Ownership, Open Ownership Principles – Verification (s.l.: Open Ownership, updated 2023), https://www.openownership.org/en/principles/verification/.

[183] Government of Jersey, Infrastructure, Housing and Environment, “Sea Fisheries (Jersey) Law 1994, Sea Fisheries (Licensing of Fishing Boats) (Jersey) Regulations 2003 – Application for a Jersey Fishing Boat Licence”, updated 4 February 2022, https://www.gov.je/SiteCollectionDocuments/Industry%20and%20finance/F%202019%20Jersey%20Fishing%20Boat%20Licence%20application%20editable%2031.01.2019.pdf.

[184] A reliable identifier is a number or reference code which is unique, stays the same over time, and can be used to check the existence of a particular corporate vehicle, such as a company or trust. Having such an identifier available and present in multiple datasets is the best way to be certain that the same entity is being referred to, and to link together a range of information about the entity and its activities. See: Kadie Armstrong and Stephen Abbott Pugh, Using reliable identifiers for corporate vehicles in beneficial ownership data (s.l.: Open Ownership, 2023), https://www.openownership.org/en/publications/using-reliable-identifiers-for-corporate-vehicles-in-beneficial-ownership-data/.

[185] For more information, see: Tymon Kiepe, “Striking a balance: Towards a more nuanced conversation about access to beneficial ownership information”, Open Ownership, 18 October 2023, https://www.openownership.org/en/blog/striking-a-balance-towards-a-more-nuanced-conversation-about-access-to-beneficial-ownership-information/.

[186] For more information, see: Armstrong and Abbott Pugh, Using reliable identifiers for corporate vehicles in beneficial ownership data.

[187] “Introducing the Legal Entity Identifier (LEI)”, Global Legal Entity Identifier Foundation, n.d., https://www.gleif.org/en/about-lei/introducing-the-legal-entity-identifier-lei.

[188] Sofia Gonzalez, Sophia Cole, and Ian Gary, Dirty Money and the Destruction of the Amazon: Uncovering the U.S. Role in Illicit Financial Flows from Environmental Crimes in the Amazon Basin (Washington, DC: the Financial Accountability and Corporate Transparency Coalition, 2023), 47, https://thefactcoalition.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/10/Dirty-Money-and-the-Destruction-of-the-Amazon-Full.pdf.