Guide to implementing beneficial ownership transparency

Legal aspects of creating a register

Creating a public BO register requires a range of legal reforms to define which entities and people will be subject to reporting requirements, as well as to mandate a range of data and systems-related considerations.

Some of the most notable tasks for legislative attention will include, among others:

- creating a legal definition of what constitutes a beneficial owner (see OO Principle of robust definitions);

- deciding on coverage of disclosures, i.e. which entities should be required to make declarations and how much of their ownership chain will need to be included in their declarations (see OO Principle of comprehensive coverage);

- creating legal sanctions for individuals and firms that fail to meet reporting obligations (see OO Principle of sanctions and enforcement);

- deciding which information will be collected in declaration forms (see Data section and OO Principle of sufficient detail);

- deciding which information will be published and how this reconciles with privacy and data protection legislation (see Publish section and OO Principle of public access);

- enabling legal reforms needed for data sharing between government registries for verification purposes (see Data section and OO Principle of verification).

Creating a definition of beneficial ownership in law

For those countries without an existing BO register, the first legislative tasks will likely comprise defining in law what constitutes BO; how this interacts with the concept of legal ownership (see Figure 1 below); and under what circumstances companies and individuals should have to make BO declarations. As the definition will constitute the foundation of the disclosure regime, it is important to ensure that no significant loopholes exist within it. For countries where a legal definition of BO already exists, meanwhile, the need to revisit legislation offers an ideal opportunity to ensure BO definitions remain in line with current best practice.

Resources

An example definition, and detailed analysis of the strengths and shortcomings of BO definitions implemented across the globe, is available in OO’s policy briefing: Beneficial ownership in law: Definitions and thresholds.

BO should be clearly and robustly defined in law, with specific thresholds used to determine when ownership and control is disclosed. Specifically:

- definitions of BO should state that a beneficial owner is a natural person;

- definitions should cover all relevant forms of ownership and control, specifying that ownership and control can be held both directly and indirectly;

- there should be a single, unified definition in law in primary legislation, with additional secondary legislation referring to this definition;

- there should be a broad, catch-all definition of what constitutes BO, coupled with a non-exhaustive list of example ways in which a BO relationship may manifest;

- thresholds [8] should be set sufficiently low so that all relevant people with BO and control interests are included in declarations, considering a risk-based approach to set lower thresholds for particular sectors, industries, or people;

- absolute values, rather than ranges, should be used to define a person’s BO or control;

- definitions should include a clear exclusion of agents, custodians, employees, intermediaries, or nominees acting on behalf of another person qualifying as a beneficial owner.

Common international practice is to include a threshold level of share ownership at which it becomes a legal requirement for a BO relationship to be disclosed (e.g. by stating in law that any individual who ultimately owns more than a 10% share in a given legal entity would qualify as one of its beneficial owners). There has been no clear international consensus over the level at which thresholds should be set, and these levels may depend on what the policy aims of the BOT reforms are. There is a trend over recent years towards lower thresholds. In its 2014 guidance on BOT, the FATF does not recommend a specific threshold level, but mentions a 25% figure in the context of examples to illustrate how thresholds would work. [9] It is relatively easy to evade disclosure by threshold if a definition does not comprehensively capture ownership and control. For instance, for a 25% threshold, a criminal working with just four allies can easily avoid disclosure requirements. It is therefore important that definitions are robust and capture substantive and less conventional means of exercising ownership and control. Some jurisdictions have also taken guidance from thresholds used in other sectors, for example, public listed companies (PLCs) or requirements under taxation laws (Tanzania harmonised its BO disclosure threshold with the ownership and control threshold in the Income Tax Act). Many jurisdictions have opted for lower thresholds. In 2020/2021, this includes Argentina (1 share or above), Kenya (10%), Nigeria (5%), Paraguay (10%), Senegal (2%), and Seychelles (10%). Trends suggest a threshold in the region of 5%-15% brings thresholds in line with evolving international standards to meet a range of policy goals. Countries can take an approach of setting lower thresholds for classes of individuals or industries that face particular risks, such as the extractive industries.

Deciding which entities should be covered

As a general principle, there should be comprehensive coverage of all relevant legal entities and natural persons in BO declarations (see also Data section). Any exemptions from disclosure requirements should be clearly defined, justified, and reassessed on an ongoing basis. This may occur, for example, where information on the ownership of such entities is collected via other means that benefit from comparable levels of quality and access (e.g. for PLCs). Where publication exemptions do exist, information on the basis for exemption should be collected.

Limited exemptions

For different reasons, some jurisdictions have considered exemptions to the disclosure of BO data for limited categories of firms, such as state owned enterprises (SOEs) and PLCs. Any exemption creates a risk of loopholes. Therefore:

- exemptions should be narrowly interpreted; and

- exemptions should be granted only when the exempt entity is already disclosing its beneficial owners to the government through alternative mechanisms.

For PLCs, risks can be reduced through the following recommendations:

- blanket exemptions from BO disclosure requirements to companies listed on any stock exchange should not be granted, as transparency and disclosure requirements differ widely between stock exchanges;

- PLCs should only be exempted from BO disclosure requirements if adequate and enforced BO disclosure requirements exist for the stock exchange(s) on which the declaring company is listed;

- all companies that are exempt from BO disclosure requirements due to their listed status should have to declare, and periodically confirm, that they are exempt due to their listed status; and

- in published BO data, PLCs should be identifiable as such; sufficient data should be collected to connect them to relevant stock exchange listings.

For SOEs, some jurisdictions have considered exemptions as these firms do not have the same kind of beneficial owners that private companies do. Citizens are technically the ultimate owners of SOEs, but have no direct control over their activities, which is usually vested in individuals that resemble typical management structures seen in the private sector. Given the substantial public resources owned or managed by SOEs, gathering information on those with significant influence or control over their activities is still highly advised. Citizens want assurances that SOEs are being well run and for public (not personal) benefit. In addition, private sector companies operating in the same market or environment also need to know the role, scope, and size of state involvement so that they can plan accordingly. Implementing countries will need to decide on what information on SOEs and PLCs will need to be collected and include any potential exemptions within its BO disclosure legislation.

Resources

Best practice for assessing how to grant disclosure exemptions to PLCs without creating loopholes has yet to be consolidated. OO has provided its contribution to the debate by outlining current thinking on when an exemption should be granted and what information should be provided in any exemption declaration.

Beneficial ownership of trusts

The ownership of trusts has implications for the implementation of BOT for legal entities, as trusts can appear in their ownership chains. A growing number of countries are taking the approach of implementing separate disclosure regimes and registers for the BOT of trusts. Where jurisdictions are implementing BOT of legal persons, and when trusts feature in the ownership structure of a legal person, the information on the BO of trusts should, at a minimum, be made available to the public.

The BOT of trusts has become a major policy and regulatory concern for international AML standard-setting bodies. The EU, via the fifth EU Anti-Money Laundering Directive (AMLD5), the FATF, via its Recommendation 10), and the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), via its Common Reporting Standard, have developed the three main international instruments dealing with BO of trusts. So far, the EU’s AMLD5 is the only international regulatory framework that requires the creation of central registers of BO of trusts as the best approach to regulate and prevent misuse. The framework also has fewer loopholes with respect to when to disclose information and what information to disclose. Best practice in the disclosure of the BO of legal entities (as covered in the OO Principles) provides a framework for thinking about how best to implement BOT of trusts, although there will be some key differences in discussions on certain aspects, such as whether information should be made public.

Resources

OO’s policy briefing on the BOT of trusts outlines implementation considerations and emerging best practice in legal and policy reforms on how to deal with trusts when implementing BOT reforms for legal entities as well as BOT of all trusts. An additional background briefing on trusts discusses the history and various types of trusts, roles of trusts parties, the legitimate and illegitimate uses of trusts, and examples of current practice on the treatment of trusts in a variety of countries.

Reporting of intermediary entities

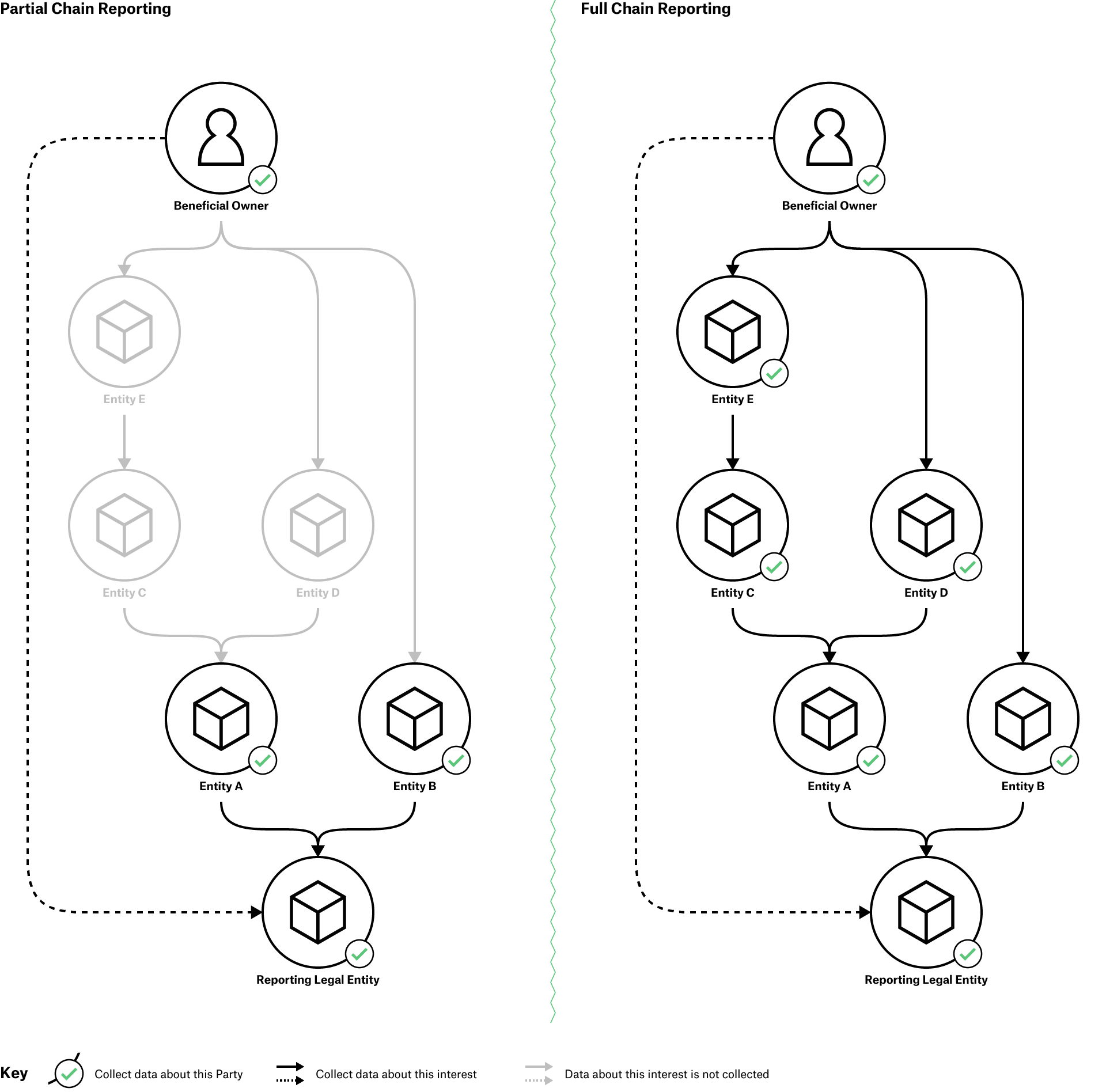

Another issue to consider at the legislative stage is how much information will be required to be disclosed about the intermediary companies and entities through which BO may be exerted. According to the OO Principle, sufficient detail should be collected about the beneficial owner, the disclosing company, and the means through which ownership or control is held. For information on ownership chains, it is common for countries to adopt requirements for declaring part of the chain, as illustrated in Figure 1. An alternative option for those committed to comprehensive disclosure would be a full chain approach, in which companies are required to disclose information on each intermediate company between the reporting entity and (a) each beneficial owner, and (b) each PLC with a stake (of above the threshold level) in the reporting entity.

Figure 1: Full versus partial ownership chain reporting

The full chain approach provides valuable detail on intermediary entities. Complete pictures of ownership structures can be highly valuable in some applications of BO data, such as in procurement. However, it is suited only to jurisdictions with reasonably advanced technology systems. This is because intermediate companies may be disclosed in multiple declarations, which brings the risk that information submitted by different entities, about the same intermediary, may not precisely tally. Whilst such discrepancies could eventually serve as a means to cross check and verify data submissions, this would require a sophisticated data verification system that would take some time to develop. For the initial iteration of registers in most countries, it is recommended to concentrate on gathering the higher quality data that would likely emerge from a more limited partial chain reporting requirement. Once the first set of data has been gathered, the declarations can then be evaluated with a view to understanding whether a more comprehensive approach would be useful.

Reconciling privacy concerns with public interest

When drafting laws to enable public access to BO data, OO generally recommends the inclusion of provisions to publish in open data format (see also Publish section).

To date, BOT has been achieved in many jurisdictions without seriously affecting the safety of the vast majority of individuals. OO’s research across a range of jurisdictions with open BO data registers has been unable to identify documented examples of harms that have arisen from publication. To minimise the risk of potential harm, countries should consider making certain personal information (for example, a beneficial owner’s personal email, phone number, home address) available to the authorities, but withholding this from the public in a system of layered access. In addition, the introduction of a protection regime would allow narrowly defined publication exemptions for natural persons where publishing personal information poses a serious risk, e.g. of domestic abuse or kidnapping. That said, their information would typically still be collected and made accessible to domestic authorities (also see Publish).

In order to ensure BO data can be made public in keeping with data protection and privacy legislation, implementers should articulate a clear purpose and legal basis for collecting and processing data when drafting legislation. Preferably, the specified purpose will be broad, based on accountability and the public interest, rather than a more narrowly defined purpose, such as AML. To navigate the provisions in domestic data protection legislation and to further minimise potential harm, governments should adhere to the principle of data minimisation: not collecting and disclosing more data than that necessary to achieve set aims (also see Publish). At the same time, however, it is important for authorities to collect sufficient information to ensure that BOT can fulfil a government’s policy intent. Similarly, when data is published, governments should seek to avoid excessive restrictions on fields for disclosure as these may, for example, make it difficult for registry users to confirm the identity of beneficial owners, or to confidently distinguish between the identities of beneficial owners with similar names or personal details. In the European context, AMLD5 recommends publishing, at a minimum, the beneficial owner’s name, country of residence, nationality, month and year of birth, plus the nature of their ownership or control of the reporting company.

For further discussion on managing potential privacy and security concerns related to BO data publication, see the OO briefings: Data protection and privacy in beneficial ownership disclosure and Making central beneficial ownership registers public.

For information on the types of specific fields that may be excluded from publication on security/privacy grounds, please refer to OO’s example declaration form.

Sanctions and enforcement

To ensure that accurate and timely information on beneficial owners is provided to authorities, an effective system of sanctions and enforcement will be needed. This involves ensuring that: 1) adequate sanctions for non-compliance exist in law; 2) agencies have a legal mandate to issue sanctions; and 3) the sanctioning body has sufficient capacity, resources, and will to verify disclosures and sanction non-compliance. Sanctions regimes work most effectively when combined with effective verification mechanisms that identify where incorrect, fraudulent, or incomplete information has been submitted (see Data section).

Introducing sanctions against the beneficial owner, registered officers of the company, and the company making the declaration helps to ensure that the deterrent effect of sanctions applies to all the key persons and entities involved in the declaration. This is also important for ensuring that data contained in registers follows the OO Principle of being up to date, and that companies report changes to their ownership structure in a timely manner.

Sanctions for non-compliance in the UK

In the UK, there are multiple sanctions against both companies and beneficial owners [10]:

- companies can be sanctioned for failure to request information from potential beneficial owners or failure to provide information on its beneficial owners to the central register;

- beneficial owners can be sanctioned for failure to respond to requests for information from companies, or for knowingly or recklessly making a false statement, as well as for failure to notify a company that they are a beneficial owner;

- for all of these offences, both the company and every officer of the company that has failed to comply are considered to have committed the offence, and the penalties are imprisonment for up to 12 months, a fine, or both; and

- CH has the ability to strike off any companies that default on their obligations to report to the register.

Selecting the appropriate agency to issue sanctions will depend largely on the political structures and preferences within the implementing country. Some jurisdictions select their state company registry, whilst others refer the matter to the ministry of justice or linked bodies that have an established investigative function. Enforcement remains a challenge for many jurisdictions, but there are numerous successful cases of sanctions being applied against non-compliant firms. Latvia’s Enterprise Register, for example, terminated 400 non-resident companies that failed to submit BO information in 2019. [11] Dozens of court rulings in Slovakia have also dealt with cases of noncompliance with BO disclosure legislation, leading in some cases to the removal of companies from the state register, making them ineligible to bid for state contracts. [12]

Resources

For more on setting and applying sanctions for those failing to provide timely and accurate BO data, see OO’s briefings on BO data in procurement and the verification of BO data.

Footnotes

[8] The level of share ownership, voting rights, and/or rights to earnings which an individual may ultimately hold in an entity before triggering obligations to report this interest to authorities.

[9] “Transparency and Beneficial Ownership”, FATF, October 2014, http://www.fatf-gafi.org/media/fatf/documents/reports/Guidance-transparency-beneficial-ownership.pdf.

[10] See: “UK Companies Act 2006”, legislation.gov.uk, n.d., https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2006/46/section/790R.

[11] Latvia’s report to Moneyval assessors, 2020. (Unpublished)

[12] See, for instance: “Zverejňovanie súdnych rozhodnutí a ďalších informácií (InfoSúd)”, Ministerstvo Spravodlivosti Slovenskej Republiky, November 2018, https://obcan.justice.sk/infosud/-/infosud/i-detail/rozhodnutie/3b90ffbc-a519-4e53-9627-329d6708b85d%3A4744e659-e5a2-42b3-a069-06abc5302a19.