Guide to implementing beneficial ownership transparency

Systems for beneficial ownership registers

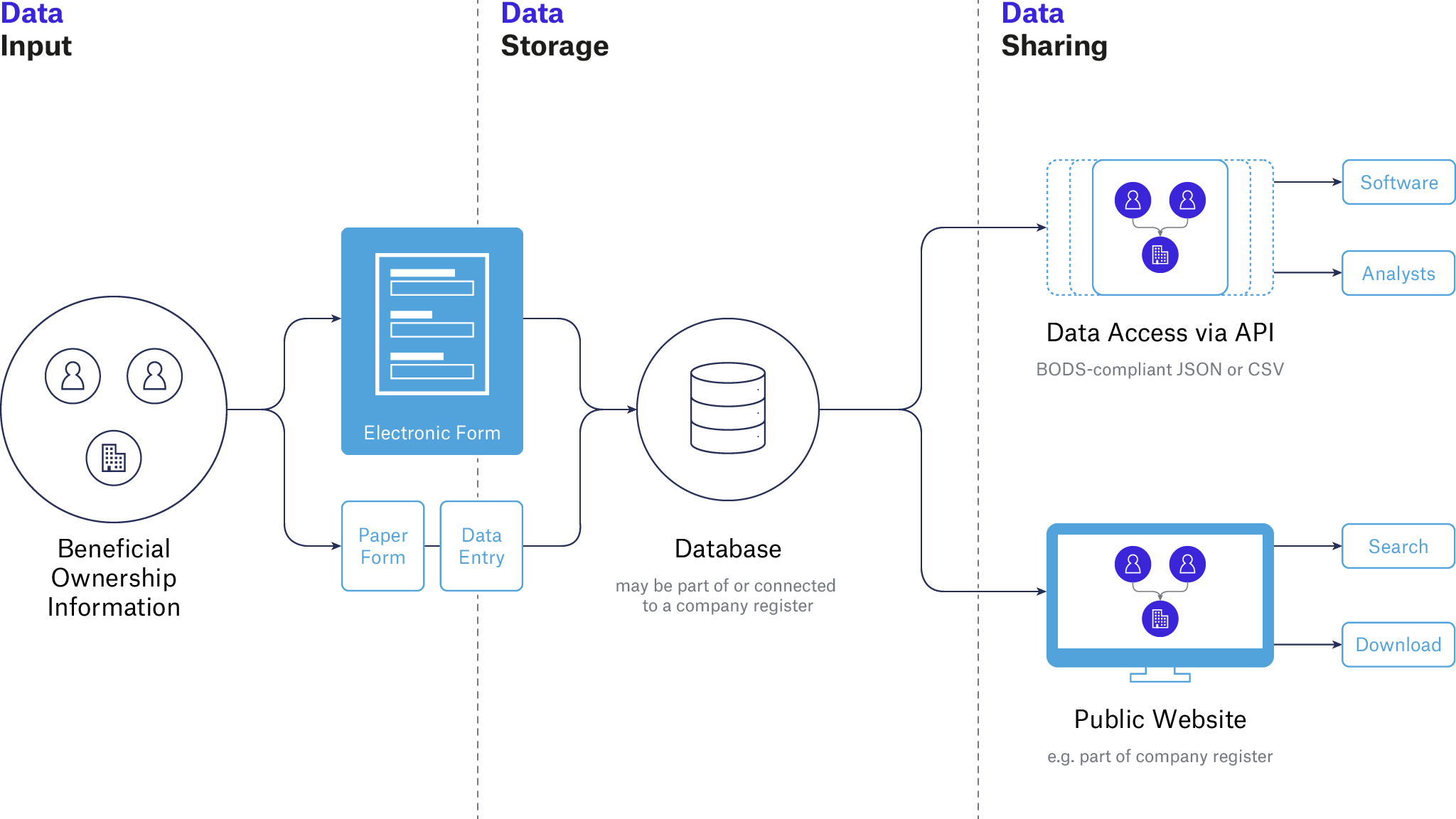

Creating a legal framework for a BO disclosure regime is only one element of a broader reform process. Facilitating BOT also requires the collection, storage, and sharing of data. This section offers guidance on how to review existing company information systems and develop them to enable the publication of BO registers.

Processes, systems, and platforms

Digital systems and administrative processes need to fit together smoothly to enable BO information to be collected, stored, maintained, exchanged, and published. Some components of systems design will need to be considered as part of legal reforms, but it will also be important to carefully consider how information flows from companies, via the jurisdiction’s systems and processes, to the people and agencies that need it. Consideration of the following questions should help to identify the starting point for work in this area, and to prompt thinking on the systems and processes that may eventually be required:

- How is the information about the companies registered in the jurisdiction currently collected and managed?

- Is information about legal ownership currently kept in the companies register? If so, how will legal ownership information be linked with BO information?

- Are there other government systems that currently collect and store company details (for example, a government procurement system)?

- How many companies will be required to submit BO declarations?

- How will companies submit their information (for example, via an online form, with a paper form, or via an authorised notary)?

- What department, or official body, will be responsible for the collection, management, and publishing of BO data?

- What manual administrative checks and operations will assist the collection and management of BO information?

- Does the jurisdiction currently publish company registration information? How will BO information be updated and made publicly available?

- How will government officials be able to access and make use of BO information (for example, by checking whether there are red flags arising from data on the BO of companies bidding for government contracts)?

- What will trigger companies to submit their first BO declaration? What will trigger them to update it?

Figure 1: BO information collection, storage and sharing pipeline

Information flow

It is useful to bring colleagues, departments, and agencies together to build a collective picture of how BO information will be handled. Among other things, this will highlight: where systems and processes need to be developed; gaps in knowledge; questions about responsibilities; and resourcing issues. Generating a diagram can be a focal point for collaboration and aid communication as work progresses. The diagrams in this section use Business Process Model and Notation (BPMN).

Most countries have digital central registers of companies that include, for example, information about companies’ legal ownership, [13] directors, founders, and registered addresses. In this case, adding BO information to the existing company register may be the best choice.

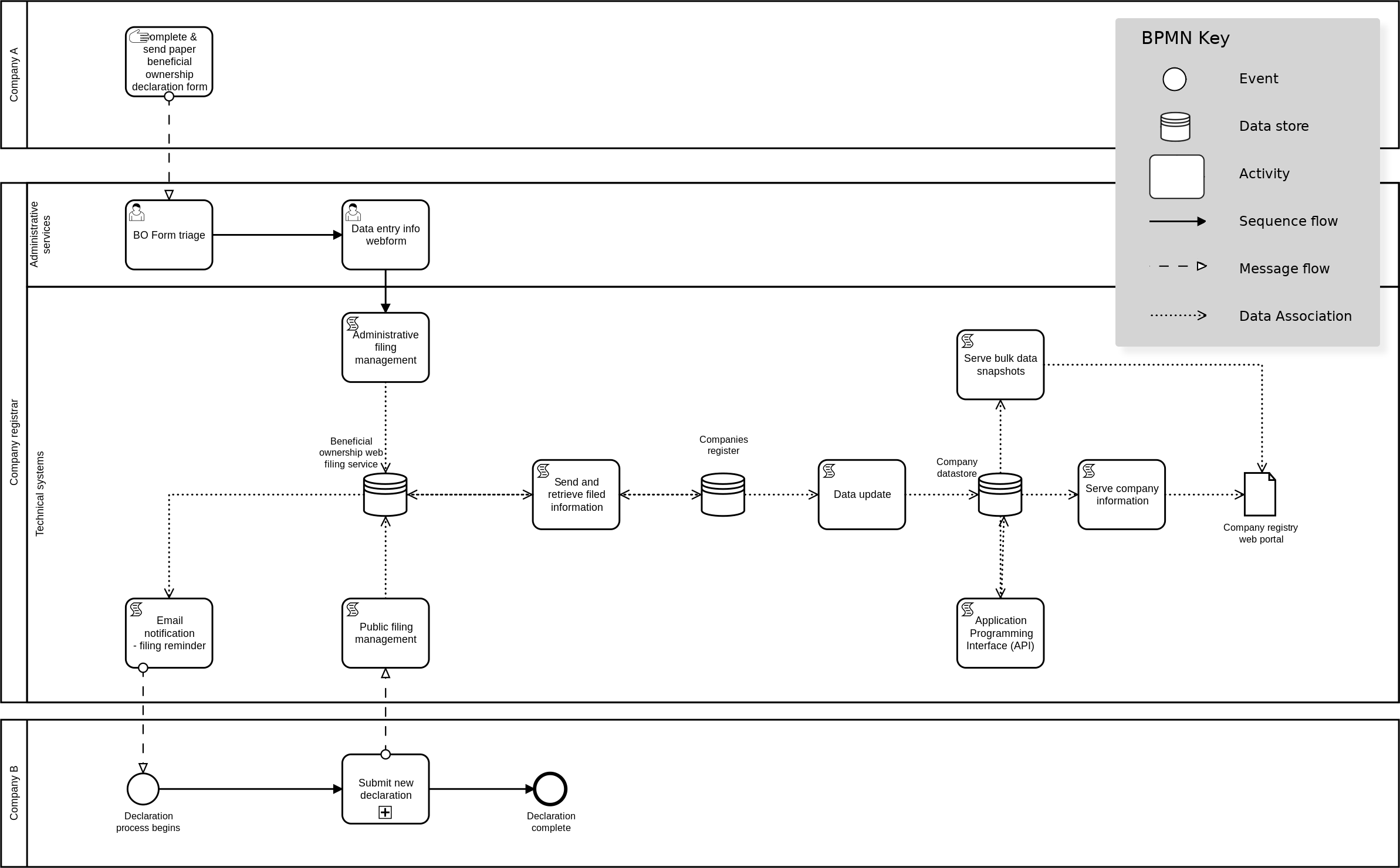

Figure 2: Example of information flow in a well-resourced implementation, using the standard BPMN format

Figure 2 shows how a company register has been extended to capture and store BO information using a new BO web filing services module. In this example, the designers of the new system have incorporated the ability for companies to file their BO information online (like company B) or via paper forms (like company A). Some work on mapping out the manual systems necessary for handling paper forms has also been done. The company datastore and related components already serve company information to the company registry portal via an application programming interface (API) [14] and bulk download services, but those would need to be updated to handle the extra BO data.

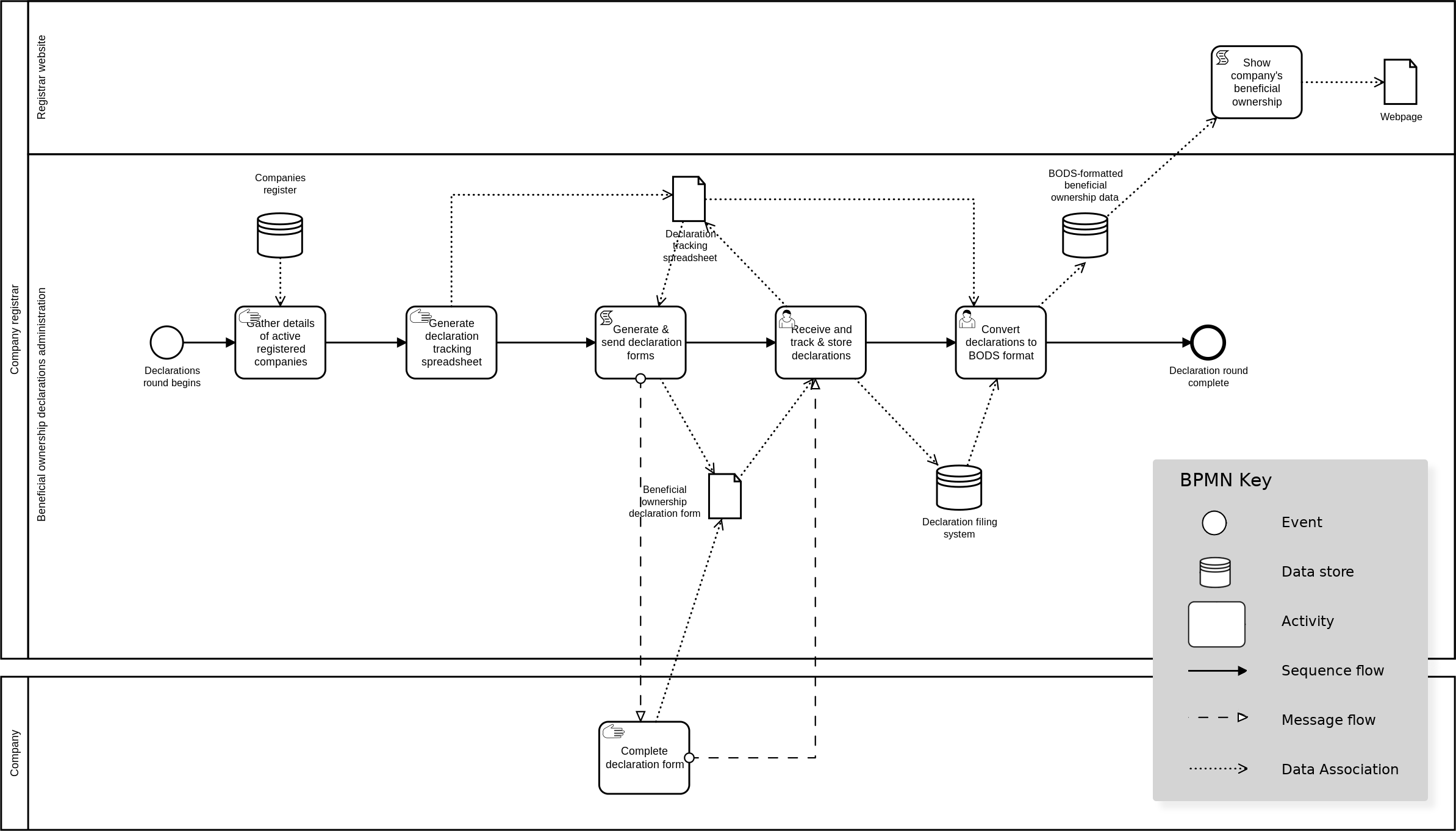

Where there are limited resources and a limited number of companies needing to declare their beneficial owners, an online declaration system may not be possible or necessary. Here, the company register itself may be paper based. Much of the administration of the gathering and publication of BO data may be managed on paper or with simple computer files and spreadsheets, as illustrated in Figure 3.

Figure 3: Example of information flow in an implementation with limited resources, using the standard BPMN format

Whatever the scale and complexity of a given country’s particular implementation, OO recommends that BO information is ultimately converted into a digital format. OO has developed the Beneficial Ownership Data Standard (BODS) for this purpose. BODS is a free-to-use, off-the-shelf template that provides a structured data format, along with guidance for collecting, sharing, and using data on BO. Publishing according to the OO Principle of structured data in BODS makes it easier to collate BO information from multiple jurisdictions (see the Data section for more on BODS).

The BODS template spreadsheet can assist conversion of BO information in paper forms to a digital format. Used alongside the data review tool, it might be a key tool where resources are limited. Where information is published in BODS format, the BODS visualiser can be embedded in websites to display company ownership and control structures.

Developing systems

As mentioned in the Commit section, consultations with key groups, staff, and audiences is crucial when developing a system for BOT. Stakeholders from both inside and outside of government, inputting, managing, or using BO information, will have valuable insights and perspectives. They should be involved early and often during the systems’ development.

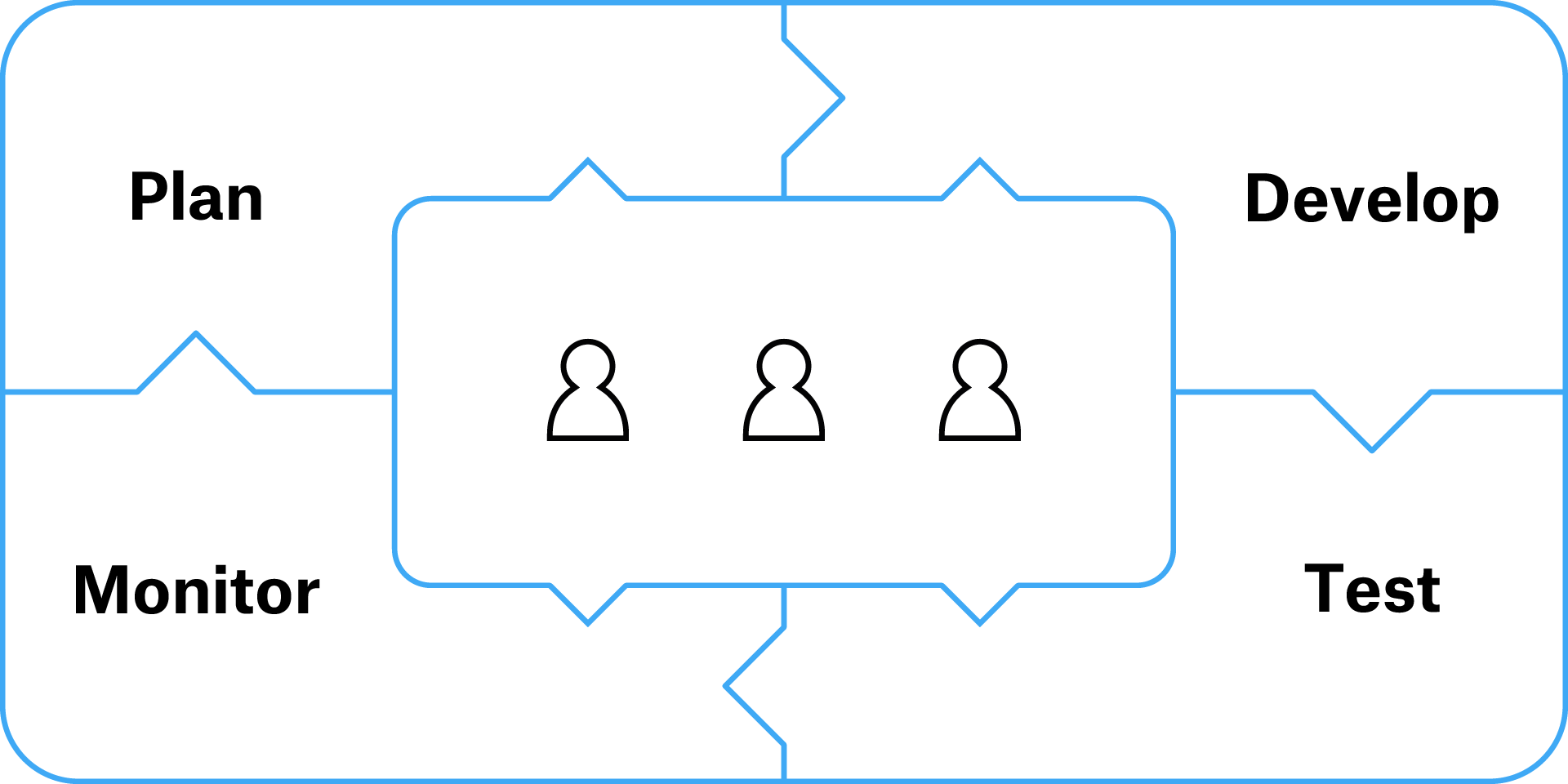

It is useful to adopt an agile approach to development. Whilst it is appealing to imagine a linear, inception-to-completion process of development where there is a clear end point, this is rarely the reality. It is better to acknowledge that systems will need ongoing improvement and adjustment. Putting people at the centre of this cycle, as illustrated in Figure 4, and securing resources for developing future versions of the systems, will prove advantageous over time. For example, focus groups or user-testing might reveal that people think beneficial owners are simply legal owners. That misunderstanding would lead to the collection of poor quality data. Revealing the problem early on allows definitions and guidance to be provided on BO forms to help people’s understanding. Not all problems can be caught the first time around, though, so securing resources for future development is crucial.

Figure 4: Putting people at the centre of systems development

Resources: See the working paper Effective consultation processes for beneficial ownership transparency reform for techniques that can be used at this stage of implementation. OO’s Beneficial ownership declaration forms: guide for regulators and designers offers advice on data collection and building usable forms.

Footnotes

[13] This primer explains how BO differs from legal ownership, which is normally recorded in company registers.

[14] An API is a mechanism that allows for interaction between separate software components.

Next page: Data considerations for beneficial ownership registers